John Stephens - Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 2 (of 2)

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Stephens - Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 2 (of 2)» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1838, Жанр: Путешествия и география, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 2 (of 2)

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:1838

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 2 (of 2): краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 2 (of 2)»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 2 (of 2) — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 2 (of 2)», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Chlopicki, the comrade of Kosciusko, was proclaimed dictator by an immense multitude in the Champ de Mars. For some time the inhabitants of Warsaw were in a delirium; the members of the patriotic association, and citizens of all classes, assembled every day, carrying arms, and with glasses in their hands, in the saloon of the theatre and at a celebrated coffee-house, discussing politics and singing patriotic songs. In the theatres the least allusion brought down thunders of applause, and at the end of the piece heralds appeared on the stage waving the banners of the dismembered provinces. In the pit they sang in chorus national hymns; the boxes answered them; and sometimes the spectators finished by scaling the stage and dancing the Mazurka and the Cracoviak.

The fatal issue of this revolution is well known. The Polish nation exerted and exhausted its utmost strength, and the whole force of the colossal empire was brought against it, and, in spite of prodigies of valour, crushed it. The moment, the only moment when gallant, chivalric, and heroic Poland could have been saved and restored to its rank among nations, was suffered to pass by, and no one came to her aid. The minister of France threw out the bold boast that a hundred thousand men stood ready to march to her assistance; but France and all Europe looked on and saw her fall. Her expiring diet ordered a levy in mass, and made a last appeal, "In the name of God; in the name of liberty; of a nation placed between life and death; in the name of kings and heroes who have fought for religion and humanity; in the name of future generations; in the name of justice and the deliverance of Europe;" but her dying appeal was unheard. Her last battle was under the walls of Warsaw; and then she would not have fallen, but even in Poland there were traitors. The governor of Warsaw blasted the laurels won in the early battles of the revolution by the blackest treason. He ordered General Romarino to withdraw eight thousand soldiers and chase the Russians beyond the frontier at Brezc. While he was gone the Russians pressed Warsaw; he could have returned in time to save it, but was stopped with directions not to advance until farther orders. In the mean time Warsaw fell, with the curse of every Pole upon the head of its governor. The traitor now lives ingloriously in Russia, disgraced and despised, while the young lieutenant is in unhappy but not unhonoured exile in Siberia.

So ended the last heroic struggle of Poland. It is dreadful to think so, but it is greatly to be feared that Poland is blotted for ever from the list of nations. Indeed, by a late imperial ukase, Poland is expunged from the map of Europe; her old and noble families are murdered, imprisoned, or in exile; her own language is excluded from the offices of government, and even from the public schools; her national character destroyed; her national dress proscribed; her national colours trampled under foot; her national banner, the white eagle of Poland, is in the dust. Warsaw is abandoned, and become a Russian city; her best citizens are wandering in exile in foreign lands, while Cossack and Circassian soldiers are filing through her streets, and the banner of Russia is waving over her walls.

Perhaps it is not relevant, but I cannot help saying that there is no exaggeration in the stories which reach us at our own doors of the misfortunes and sufferings of Polish exiles. I have met them wandering in many different countries, and particularly I remember one at Cairo. He had fought during the whole Polish revolution, and made his escape when Warsaw fell. He was a man of about thirty-five years of age, dressed in a worn military frockcoat, and carrying himself with a manly and martial air. He had left a wife and two children at Warsaw. At Constantinople he had written to the emperor requesting permission to return, and even promising never again to take up arms against Russia, but had received for answer that the amnesty was over and the day of grace was past; and the unfortunate Pole was then wandering about the world like a cavalier of fortune or a knight of romance, with nothing to depend upon but his sword. He had offered his services to the sultan and to the Pacha of Egypt; he was then poor, and, with the bearing of a gentleman and the pride of a soldier, was literally begging his bread. I could sympathize in the misfortunes of an exiled Pole, and felt that his distress must indeed be great, that he who had perilled life and ties dearer than life in the cause of an oppressed country, should offer his untarnished sword to the greatest despot that ever lived.

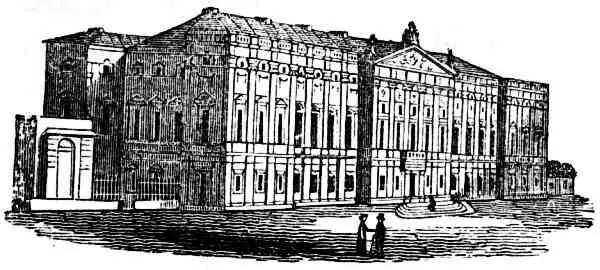

The general appearance of Warsaw is imposing. It stands on a hill of considerable elevation on the left bank of the Vistula; the Zamech or Chateau of the Kings of Poland spreads its wings midway between the river and the summit of the hill, and churches and towering spires checker at different heights the distant horizon. Most of the houses are built of stone, or brick stuccoed; they are numbered in one continued series throughout the city, beginning from the royal palace (occupied by Paskiewitch), which is numbered one , and rising above number five thousand. The churches are numerous and magnificent; the palaces, public buildings, and many of the mansions of noblemen, are on a large scale, very showy, and, in general, striking for their architectural designs. One great street runs irregularly through the whole city, of which Miodowa, or Honey-street, and the Novoy Swiat, or New World, are the principal and most modern portions. As in all aristocratic cities, the streets are badly paved, and have no trottoirs for the foot passengers. The Russian drosky is in common use; the public carriages are like those in Western Europe, though of a low form; the linings generally painted red; the horses large and handsome, with large collars of red or green, covered with small brass rings, which sound like tinkling bells; and the carts are like those in our own city, only longer and lower, and more like our brewer's dray. The hotels are numerous, generally kept in some of the old palaces, and at the entrance of each stands a large porter, with a cocked hat and silver-headed cane, to show travellers to their apartments and receive the names of visiters. There are two principal kukiernia, something like the French cafés, where many of the Varsovians breakfast and lounge in the mornings.

Royal Palace at Warsaw.

The Poles, in their features, looks, customs, and manners, resemble Asiatics rather than Europeans; and they are, no doubt, descended from Tartar ancestors. Though belonging to the Sclavonic race, which occupies nearly the whole extent of the vast plains of Western Europe, they have advanced more than the others from the rude and barbarous state which characterizes this race; and this is particularly manifest at Warsaw. An eyewitness, describing the appearance of the Polish deputies at Paris sent to announce the election of Henry of Anjou as successor of Sigismund, says, "It is impossible to describe the general astonishment when we saw these ambassadors in long robes, fur caps, sabres, arrows, and quivers; but our admiration was excessive when we saw the sumptuousness of their equipages; the scabbards of their swords adorned with jewels; their bridles, saddles, and horse-cloths decked in the same way," &c.

But none of this barbaric display is now seen in the streets of Warsaw. Indeed, immediately on entering it I was struck with the European aspect of things. It seemed almost, though not quite, like a city of Western Europe, which may, perhaps, be ascribed, in a great measure, to the entire absence of the semi-Asiatic costumes so prevalent in all the cities of Russia, and even at St. Petersburgh; and the only thing I remarked peculiar in the dress of the inhabitants was the remnant of a barbarous taste for show, exhibiting itself in large breastpins, shirt-buttons, and gold chains over the vest; the mustache is universally worn. During the war of the revolution immediately succeeding our own, Warsaw stood the heaviest brunt; and when Kosciusko fell fighting before it, its population was reduced to seventy five thousand. Since that time it has increased, and is supposed now to be one hundred and forty thousand, thirty thousand of whom are Jews. Calamity after calamity has befallen Warsaw; still its appearance is that of a gay city. Society consists altogether of two distinct and distant orders, the nobles and the peasantry, without any intermediate degrees. I except, of course, the Jews, who form a large item in her population, and whose long beards, thin and anxious faces, and piercing eyes met me at every corner of Warsaw. The peasants are in the lowest stage of mental degradation. The nobles, who are more numerous than in any other country in Europe, have always, in the eyes of the public, formed the people of Poland. They are brave, prompt, frank, hospitable, and gay, and have long been called the French of the North, being French in their habits, fond of amusements, and living in the open air, like the lounger in the Palais Royal, the Tuileries, the Boulevards, and Luxembourgh, and particularly French in their political feelings, the surges of a revolution in Paris being always felt at Warsaw. They regard the Germans with mingled contempt and aversion, calling them "dumb" in contrast with their own fluency and loquacity; and before their fall were called by their neighbours the "proud Poles." They consider it the deepest disgrace to practise any profession, even law or medicine, and, in case of utmost necessity, prefer the plough. A Sicilian, a fellow-passenger from Palermo to Naples, who one moment was groaning in the agony of seasickness and the next playing on his violin, said to me, "Canta il, signore?" "Do you sing?" I answered "No;" and he continued, "Suonate?" "Do you play?" I again answered "No;" and he asked me, with great simplicity, "Cosa fatte? Niente?" "What do you do? Nothing?" and I might have addressed the same question to every Pole in Warsaw.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 2 (of 2)»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 2 (of 2)» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 2 (of 2)» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![William Frith - John Leech, His Life and Work. Vol. 1 [of 2]](/books/747171/william-frith-john-leech-his-life-and-work-vol-thumb.webp)

![William Frith - John Leech, His Life and Work, Vol. 2 [of 2]](/books/748201/william-frith-john-leech-his-life-and-work-vol-thumb.webp)