The Grande Armée had ventured into a swamp, pursued an army of ghosts, and obtained half a victory.

All that for a heap of ashes.

Why had Napoleon dug his heels in while in Moscow? Why had he allowed the jaws of winter to close on him? He had thought that, by occupying the economic capital, the Tsar would be cornered and end up pleading for a peace treaty. The French emperor had already harbored such illusions by the River Neman. In the smoking rubble of Moscow, he kept feeding on his own hopes. Misled by his self-confidence, he did not listen to General de Caulaincourt, who was urging him to leave.

While the King of Kings procrastinated, in Saint Petersburg Alexander remained inflexible. You do not negotiate with the devil. He was no longer the French sovereign’s friend, but then had he ever been that? Napoleon had overlooked something: that Saint Petersburg, the spiritual capital, was more important in Alexander’s eyes than the secular capital. Moscow could fall, burn down, vanish from the map, but Russia would remain.

So time passed in the soot dust. From September 15th to October 19th, eating his heart out, drawing up plans, ruling the Empire from a distance through a system of express mail and dispatch riders organized by Caulaincourt, Napoleon waited, hoped, and convinced himself. He lost a month. The troops of General Winter had time to get ready for attack.

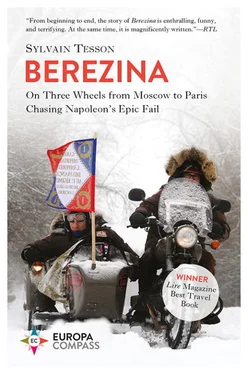

So, we backfired along Kutuzov Avenue. Moscow, the large capital of iron, steel, tears, and stars, was pushing us out through the West Gate, the name of which is associated with all the woes of the Grande Armée .

On the avenue, a car brushed past us, the window opened, and a young Russian with a pointy nose shouted, “Tired of life, are you, guys?”

“Shut up, you jerk,” I said. Driving does not raise the standard of your thoughts.

Russians have paved the path of their history with glorious monuments and compelling statues. We came across one of Kutuzov the Fat and one of Gagarin. Then there was a war plane during take-off on a pedestal. Then we reached the suburbs: we were on the road to Moyjak when a notice appeared that confirmed that our journey no longer belonged just to the realm of dreams, pleasant distractions, or drunken projects: “Borodino, fifty-five miles.”

The bike was rocking terribly, with Goisque too heavy at the back; Gras, asleep in the sidecar, wasn’t counterbalancing the profile shift. It was like being on an unmaneuverable raft with my two friends. Both were imperturbable. For years they had been traveling around the world in the worst possible conditions without a single complaint.

Gras, 30, had kept his childish habits. He drank nearly a gallon of pineapple juice a day, swam in the pool for two hours, fed on chocolate, and looked like a high-strung hockey champion. He’d been living in the old Soviet Empire for eight years, learned Russian in Omsk, and stayed in Vladivostok for four. He enjoyed silence and had found Siberia to match his melancholy disposition. Later, he had become the director of the Alliance Française in Donetsk, in the Ukrainian Donbas region. His Russian friends considered him one of their own. His female students were secretly in love with him. His work superiors envied his detachment. The old fogies at the Embassy slightly dreaded this ironic young hussar who felt so at ease in the country’s society. He was preparing a thesis in Geography on the borders of empires. He would quite happily never have left mountain peaks, deep forests, and this desolate geography which, just by itself, suited his sadness. He channelled his love for Russia into beautiful books his blond students read in full in the hope of attracting a look from their teacher. His black hair and dark skin never failed to attract the favor of Slav girls, while cops would frequently check on him because they mistook him for a Chechen. Once, in Pakistan, he broke a leg on a mountain wall and had to wait twenty-four hours for help, hanging off a piton at an altitude of sixteen thousand five hundred feet without worrying too much. Whenever we went walking in the forest or tackled a summit climb, he made it a point of honor not to carry enough equipment. He considered foresight vulgar. Soon enough, the situation would turn critical and then Gras, feeling in his element, would double his efforts to get out of the tight spot. The rest of the time, he was bored and couldn’t care less.

Goisque was earthier. He wouldn’t have been out of place in a Soissons trench in 1914. He was from Picardy, and attached to his land like a boot to clay. After visiting a hundred countries, he still considered a field of beets exhausted by the drizzle the most beautiful spectacle the planet could offer. His Antwerp stevedore build was at odds with his fine hands. A pair of piercing blue eyes shielded by Neanderthal eyebrows completed his paradoxical look, as though nature had refused to grant him any gradation between brutality and finesse. He’d been taking photos of the world for the French press for twenty-five years. His style was eclectic. He would accompany the minister to Afghanistan one day, jump above the Volga with Russian parachutists the next, then spend two weeks on board the Charles-de-Gaulle before going off to report on masseuses in the Mekong delta. We’d camped together in the Gobi Desert, the Siberian Taiga, by the Caspian Sea, in Tibet and Afghanistan, and by the fire he’d tell me about his time as a UN Peacekeeper, his years as a humanitarian volunteer in the Cambodian jungle, crossing the ocean on a Vietnamese junk boat, traveling to Kapisa, Sudan, and the Caucasus. He’d conclude, much to my annoyance, that none of these memories was a patch on spending a spring morning in a farmhouse full of children’s shrieks. Goisque had one obsession in his reports: the light. It was his passion, his obsession. If the sky had been clear that day, he could go to sleep on the ground, in the cold, with a bone to chew on, and a blissful smile on his face. But if the light had been scarce, not even the most luxurious hotel or the friendliest company could distract him from his rambling: “It’s all screwed, this shitty report.” I therefore had beside me a pessimistic dandy and a photon monomaniac. A fine combination.

We weren’t dressed warmly enough, the 1.4°F air was biting at my kneecaps, and Latvian trucks, looming huge at our weak rear, would brush past us, spattering our jackets with snow. Doubt was worming its way into me: what the hell was I doing on a Ural in the middle of December, with two fools in tow, when these damned machines are made to transport small, 90-pound Ukrainian women from Yalta beach to Simferopol on a summer afternoon?

All around us there was ice, snowdrifts, gray suburbs, crumbling factories, and crooked isbas . The landscape had a hangover. Even the trees grew askew. The sky was the color of dirty flannel. And the salty mud churned out by thirty-three-ton trucks gave us a taste of polluted fish in our mouths.

A motorbike helmet is a meditation cell. Trapped inside, ideas circulate better than in the open air. It would be ideal to be able to smoke in there. Sadly, the lack of space in an integral crash helmet prevents one from drawing on a Havana cigar, and the ensuing wind blows out the burning tip when the helmet is open. A helmet is also a sounding box. It’s nice to sing inside it. It’s like being in a recording studio. I hummed the epigraph from Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night . These lines were to become my mantra for the weeks to come:

Our life is a journey

Through winter and night

We try to find our way

Beneath a sky without light

The lady at the service station got frightened. With all our layers of clothing, we looked like cosmonauts.

Читать дальше