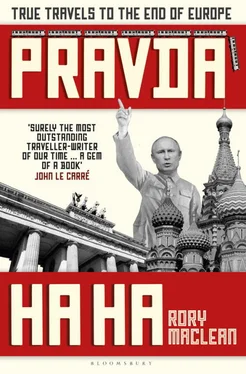

Rory MacLean - Pravda Ha Ha - True Travels to the End of Europe

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Rory MacLean - Pravda Ha Ha - True Travels to the End of Europe» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2019, ISBN: 2019, Издательство: Bloomsbury Publishing, Жанр: Путешествия и география, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Pravda Ha Ha: True Travels to the End of Europe

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2019

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-4088-9652-5

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pravda Ha Ha: True Travels to the End of Europe: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Pravda Ha Ha: True Travels to the End of Europe»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Pravda Ha Ha: True Travels to the End of Europe — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Pravda Ha Ha: True Travels to the End of Europe», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Charity hardly left her bunk for the first days. She kept her thoughts to herself, telling the doctors only that she had been kidnapped. Her details were registered with Frontex, the EU border agency, and she was transferred in a group to Messina and then to the Italian mainland. At the camp she was told that she was free, that she need do only what she wanted. But she had no money, and groups of West African men loitered on the breezeblock wall at the entrance. As soon as she received her travel document, she vanished.

Where she went, what she did, how she fed herself, she would not tell me. She simply dropped out of sight, leaving no trace: no mobile phone trail, no asylum registration, no claim for financial support. She ceased to exist, her name and number deleted from the Italian registry after a year. No one looked for her, and it seems no one looked after her, until she turned up in Berlin.

A couple of months before I reached the city she passed through the Moabit LaGeSo Refugee Welcome Centre – around the corner from Thomas Brussig’s home – and was given a bed at Tempelhof. The old airport which had kept the city alive during the Berlin Airlift now sustained its newest residents. Its hangars had been lined with ranks of white tents. On its noticeboards German lessons were advertised in Arabic, Farsi, Russian, Somali and Vietnamese. Syrian fathers pushed hand-me-down prams along the airport apron. Young Uzbeks lounged at mobile phone charge points. To date Germany has given shelter to almost two million refugees in a noble and magnanimous act of humanity and contrition.

Vertriebene has a special meaning for Germans, the word understood more as ‘the evicted’ rather than ‘refugees’. It is replete with the memory of the millions of ethnic Germans expelled from Soviet territories after the war. A Berlin friend of mine works as a volunteer at Tempelhof, manning its dozen washing machines. Every day, all day, refugees bring their clothes to her. Few words are spoken, no names exchanged. The work is numbing, humbling and essential. My friend puts the dirty laundry in a numbered basket and issues a numbered receipt, which is needed to retrieve it.

But Charity lost her receipt. She forgot her number. She hovered near to the machines for a day and a half, hoping to see her clothes. When she didn’t spot them, she summoned the courage to approach my friend. In broken German she explained her loss. She fought to hold back the tears. Together the two women looked through the numbers and in cupboards. After an hour they found the clothes, in a machine that had broken down mid-cycle and was awaiting repair in a far storeroom. In the murky water was all that Charity owned in the world. My friend asked for her name, not her number, and Charity broke down and wept.

Over the next few weeks I met her four or five times in my friend’s apartment. My friend – like tens of thousands of Germans across the country – acted as a kind of foster parent, guiding Charity through the bureaucratic jungle, helping her to translate and file the papers necessary to claim asylum. She also taught her how to ride a bicycle. During that time, when not filling out forms, Charity told me her story – her odyssey – while sitting with us by the kitchen window. There was a delicacy about her: oval face, plain headscarf, teeth as white as her eyes that were always focused on the floor. She sat by a window, she said, to forget the lightless Tripoli cell.

‘ Hier bin ich sicher ,’ she assured me, a breeze lifting the curtains. I’m safe here. But somehow I sensed that she didn’t believe it.

Charity wanted to make herself useful, she said, and my friend found her unpaid work at a nearby cemetery. Sprawling Weissensee was the largest Jewish burial ground in Europe, the final resting place of more than 100,000 Berliners, yet today it is all but deserted. Ivy has crept into its pre-war tombs and cracked its stones. Brambles have swallowed its grandiose Wilhelmine monuments. Under the Nazis, Weissensee was closed and the city’s Jews sent to distant death camps. Urn fields of ashes from Auschwitz, Bełżec and Bergen-Belsen now fan out from the old mausoleums. Almost no one remains alive in Berlin to remember its dead.

Charity pushed her wheelbarrow around the graves. She walked the overgrown paths and cut back the wild ivy from sunken headstones. As she worked her family often came to her in visions, she told me, her father staring from a far copse of trees, her mother’s shadow falling across a collapsed tomb. She also said that she saw other ghosts but she didn’t understand their language.

‘Sometimes I feel so helpless. Sometimes I wake up asking, “Why did I wake?”’ she told my friend in the quietest voice.

I wasn’t in Berlin when she disappeared again. Her asylum claim had been refused, as first requests often are. My friend had sat with her, explaining how to reapply but Charity just stared out of the window as if she might slip through it. It was winter by then and she’d pointed at the bare chestnut tree in the courtyard garden and said, ‘Soon there will be birds in the tree, and a nest, and leaves to hide the nest.’ Together they’d drunk tea until the pot was empty. When Charity had stood to leave she’d added to my friend, ‘God keep you.’

She didn’t turn up for work in Weissensee. She failed to appear at the refugee cafe at the weekend. At the hostel my friend learned that she had simply left with her raffia bag, telling another Eritrean that she had to meet someone in Italy.

My friend mourned Charity’s passing, blaming herself for not doing enough. She revisited the rejected application again and again. But then she moved on, as she had to do, volunteering to mentor twins from Iraq while keeping Charity’s memory in her heart. She even persuaded two German neighbours to help her at Tempelhof.

‘My neighbours were as scared as the Iraqi girls,’ said my friend. ‘I told them, “Take my hand, and you’ll find a person that touches you, who opens your heart. You may even fall in love with their story and then really be able to help them.”’

Mitläufer , the German word for ‘fellow traveller’, can be used in a metaphorical sense, meaning to walk alongside another person. I tried to envision myself in Charity’s shoes. I wanted to imagine her experience: the feel of the clothes on her back, the reek of sun-blistered flesh in the drifting metal hull, the sound of a gang rape in the next cell. I tried to conjure up her missing year, about which she would not talk. I could only guess at the magnitude of her suffering.

At Schönefeld airport – predecessor to Berlin Brandenburg – a broad underground passageway ran from the S-Bahn station to the terminal building. On my last evening in the city I hurried along it to catch a late-night flight. At the tunnel’s far end there appeared ten, then a hundred, perhaps a thousand people, led by a dozen uniformed officials. The mass of humanity filled the wide subway, blocking my path, threatening to overwhelm me. I stopped in my tracks and let the crowd flow around me: Romanian mothers in purple headscarfs, gaunt Africans clutching large official envelopes, teenage Pakistanis carrying sleeping bags in Ikea bags, an elderly Ethiopian walking with a cane. Almost none of the Vertriebene – the expelled – wanted to be there. Almost all of them had had to make an impossible choice. I could never know all the details of course, of decisions made when there were no good options, of stealing from a parent, driving a Hilux or shouldering a Kalashnikov to save oneself and one’s family. All I could do was to pick out one or two faces in the crowd, to envisage their lives and to tell their individual stories.

‘When I think of my journey, I can hardly believe it all happened,’ Yusra Mardini told me. ‘When I read about it in the book, and when I see the film, I cry. I laugh. Of course it isn’t a hundred per cent as I lived it, no book or film can ever be, but in my heart is a sense of great responsibility, that my story can help people, that it can give them hope.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Pravda Ha Ha: True Travels to the End of Europe»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Pravda Ha Ha: True Travels to the End of Europe» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Pravda Ha Ha: True Travels to the End of Europe» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Эдвард Докс - Pravda ['Self Help' in the UK]](/books/33503/edvard-doks-pravda-self-help-in-the-uk-thumb.webp)