Fig. 12.Sophia Engastromenos in the “Great Diadem” from the “Priam treasure” (1874).

The treasures found by Schliemann could not have belonged to legendary Priam, as they were found in the cultural layer that was a thousand years older than Homer’s Troy.

The Sublime Porte read the newspapers, too, and having learned about Schliemann’s unprecedented smuggling, sued him for ten thousand francs. Silently grinning, the millionaire reimbursed the damage, added extra forty thousand and declared himself the absolute owner of the treasures. Later Schliemann made several attempts to place them in museums in London, Paris and Naples, but they refused to take the treasures for political and financial reasons. [23] In 1876 Russian Archaeological Society was trying to buy Schliemann’s collection. However, the price was unaffordable.

In 1881, Schliemann eventually presented the “Priam treasures” to the city of Berlin, having received the title of the “honourable citizen of Berlin” in exchange, a title, that was previously conferred to Chancellor Otto von Bismark. The treasures remained there until Professor Wilhelm Unverzagt transferred the Trojan finds to the Soviet Command in 1945 according to contribution conditions. For a long time, the collection was considered to be lost, but it was actually stored in strict confidence in the Pushkin Museum of Moscow (259 items, including the “Priam treasures”) and in the State Hermitage (414 items made of copper, bronze and clay). It was only in 1993 that Yeltsin’s Government declared that the most valuable part of the Trojan treasures were being kept in Russia. On April 15[[th]], 1996, the trophies were exhibited in the Pushkin Museum for the first time. [24] After the exhibition several countries claimed “the treasures of Priam”: Germany (who received it as a gift), Turkey (where they were found), and even Greece (where they had supposedly belonged).

Having found the “Priam treasures”, Schliemann did not cease his exploratory activity and continued to dig out Mycenae, Orchomenos and Tiryns. He returned to working at the Hisarlik Hill for three times. While different people think differently about Schliemann’s activities, it is noteworthy that his adventures not only peaked scientific interest in the history of Troy, but also resulted in discovery of the previously unknown Aegean civilization. Schliemann never learned about it and died in certainty that all his finds were only related to the Trojan War era.

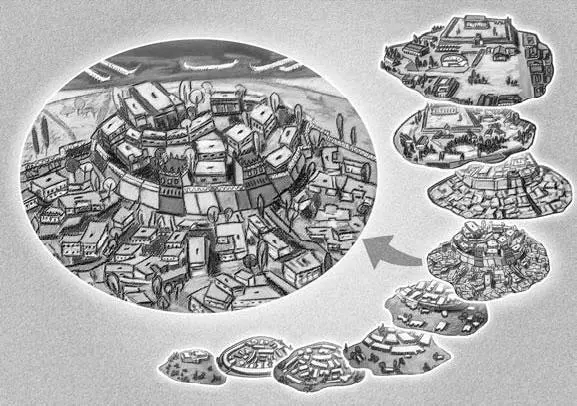

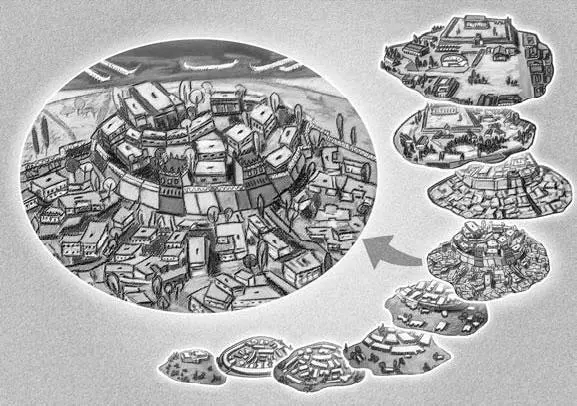

After Schliemann’s death, in 1893–1894, his friend and colleague Wilhelm Dörpfeld studied the stratigraphy of the archaeological layers of the Hisarlik Hill in more detail and determined that nine cities had replaced each other in sequence during the course of nearly 4.5 millennia in that spot. Accordingly, the periods of Troy’s existence were numbered from 1 to 9. In Dörpfeld’s opinion, Homer’s Ilion lied in the sixth layer (Troy 6), which Schliemann ruthlessly destroyed during his first excavations. Dörpfeld arrived at this conclusion even despite the fact that no traces of military operations were found in relation to destruction of Troy 6.

In 1932 Dörpfeld’s business was continued by the expedition of the Cincinnati University, headed by Carl Blegen, a renowned American archaeologist. Blegen corrected his predecessor and proved that Troy 6 (1800–1300 B.C.) had perished due to an extremely strong earthquake. Blegen divided the Troy 7 epoch into three periods and suggested that Homer’s Troy had existed in the 7а period (1300–1100 B.C.), with its apparent signs of a siege and damage.

The diagram proposed by Carl Blegen in relation to the sequence of existence and destruction of ancient settlements on the Hisarlik Hill became a classical one.

Troy 1 (3000–2500 B.C.) dates back to the pre-Greek culture, as ancient as most ancient civilizations, such as the Egyptian, Sumerian, Aegean and Indus ones. Inhabitants of Troy 1 had no gold, but lived in rather good houses, called megarons, they used metal tools and bred sheep and goats.

Fig. 13.According to Dörpfeld and Blegen, the Trojan settlement is a kind of a sandwich cake. (Image © Nika Tya-Sen.)

Troy 2 (2500–2200 B.C.) was a large city of the Minoan culture with walls of four meters thick, cobbled streets and gates. The basic activity of its inhabitants was agriculture: manual grinding mills were found in almost every house of this city. They used potter’s wheels to make utensils. Troy 2 traded fabrics, wool, ceramics and timber in the huge territory from Bulgaria and Thrace up to Central Anatolia and Syria, which promoted noticeable growth of its financial well-being, demonstrated by a great number of golden and silver items found in this cultural layer, including the “Priam treasure” found by Schliemann.

The city was destroyed by a sudden fire, and locals had no time to collect their precious utensils. However, according to Blegen, the catastrophe “did not cause any significant damage to the settlement’s cultural development. Given the retention of the former civilization and absence of obvious traces of foreign influence, the culture of Troy 2 was gradually and steadily developed until its successor Troy 3 picked up the baton”. [25] Carl Blegen, Troy and the Trojans .

Troy 3 (2200–2050 B.C.) and Troy 4 (2050–1900 B.C.) were established on the site of the capital that burnt-down. They were protected with walls and occupied a large area. Despite the rather primitive (even compared to Troy 2) culture in general, the population of these cities improved upon cooking methods and notably varied their diet.

Troy 5 (1900–1800 B.C.) was a city with a quite high culture level given the samples of fine ceramics and building art discovered. Compared to the previous periods, the manners and habits of the citizens changed a lot. “One of the innovations that was introduced in Troy 5 (which archaeologists regret strongly) was procedding to a new and more efficient way of house cleaning. Now they swept the floor and cleaned it from the rubbish accumulated during the day; therefore, nowadays archaeologists can only rarely find animal bones, various small items discarded and lost, as well as whole or broken ceramic vessels”. [26] Carl Blegen, Troy and the Trojans.

Like the previous cities standing on Hisarlik Hill, Troy of that period was destroyed, although the cause for this remains unknown: there are no traces of a fire in the ruins of buildings, and nothing would confirm that the city was captured by enemies.

Fig. 14.The Southwest (Scaean) gate where Schliemann excavated the “Priam treasure” dates back to the Troy 2 period.

Troy 6 (1800–1300 B.C.) was a really great city with block walls of 5 meters thick and with four gates, with squares and palaces. Its population were people of foreign traditions, who apparently came there from another place and brought their own cultural legacy with them. They tamed horses, established a custom of cremation of the deceased, and perfected the art of weapons production. As early as in the beginning of the Troy 6 period, the range of pottery wares had been changed to something new. This city was leveled by an earthquake, as evidenced by specific cracks on walls of buildings.

Читать дальше