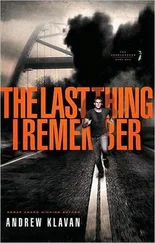

Andrew Klavan

IF WE SURVIVE

This book is for John and Julie Nolte.

We were in the cantina waiting for a bus when Mendoza walked in and shot the waiter dead. It happened just like that, that fast. One second we were sitting around our table in the corner, drinking our Cokes, making conversation, eager to go home, looking forward to seeing our families again, to seeing America again. The next second the whole world seemed to explode with a deafening blam!

I jumped in my seat, shocked. I turned—and I saw the whole thing right in front of me, a sort of frozen tableau. There was Mendoza, in his rebel fatigues and red bandanna. His arm was extended. A wicked-looking pistol was in his hand. Smoke was still trailing upward out of the barrel.

The waiter was in front of him. Carlos—that was his name. A tall, round-bellied man with an easy smile. He didn’t speak much English, but he liked to joke with us all the same, liked to flirt with the girls and nudge the guys as if to say, You see, my friend, this is how you talk to the ladies . This is how you charm them .

For one second—one second that seemed to go on forever— Carlos remained where he was—captured in the moment of reeling backward—a look of terror and sadness stamped on his features.

For that one second, that one endless second, we all seemed frozen, locked into that same terrible tableau. Pastor Ron, Jim, Nicki, Meredith, me. All of us motionless—frozen—as if we would never move again; all of us staring at the scene—our eyes wide, our mouths open.

Then Carlos fell. He began to take a step back as if the impact of the bullet was going to blow him across the room. But then—no—he just collapsed, his legs folding under him like pieces of string. I had never seen a dead man before, but somehow I knew from the way he went down that it was over for him.

The next second everything started moving again, moving very quickly. There was the sound of footsteps—a thunder of footsteps that seemed to come from all around us, shaking the floor and the walls. There were shouts from the street outside and then there were shouts in the cantina too. Deep, angry, threatening shouts. I heard a muttered curse from somewhere close to me. I heard a woman start to scream and then suddenly stop.

I looked around me. Men—all of them dressed like Mendoza—all of them in fatigues with red bandannas tied around their heads—were charging through the cantina’s swinging doors. They were spreading out around the room, flooding the room, lining the walls, blocking the exits. Every one of them was holding a gun—the sort of machine gun you always see in action movies and on the TV news with the bullet magazine curling out the bottom of it.

Two of the men posted themselves by the front door. Two others cut off the path to the back hall and the rear entrance. Another two blocked the stairway that led to the hotel rooms upstairs. They stood there with their machine guns raised to their chests and eyed the room, eyed all of us, with a look that said, Just try to get past us . Just try, and see what we do to you .

No one tried.

It was all over in a second. That fast, we were surrounded. Trapped.

What happened next—the bloodshed, the tragedy, the sheer terror—nearly defies belief.

But I guess I’d better start at the beginning.

There were five of us before the killing started. We had come to Costa Verdes to build a wall.

It was a poor country. A jungle country. A small country set on that narrow, twisting bridge of land that links Mexico to Colombia: Central America. The village we were in—Santiago—was a nothing of a place. Just a church in a flagstone plaza. A three-story-tall cantina-slash-hotel. A narrow street of shops and market stalls. And houses— little cottages really—trailing away up the road and into the mountains.

There were a lot of mountains in Costa Verdes. There were mountains everywhere, as far as the eye could see. They rose against the pale-blue sky in the morning, hunkered under black thunderclouds in the afternoon, and stood silhouetted beneath the stars at night. They were covered with forest, deep beryl green up close, blue-gray in the distance. And there was always mist rising out of the trees, spreading over the peaks and covering the horizon with an aura of mystery.

As for the wall we were building here in the village, it was the wall of a school—the only school for miles around. Not only the kids in the village used it, but all the kids from the farms and plantations on the nearby slopes: two dozen kids, maybe more, and of all ages. The wall had been destroyed somehow—I wasn’t sure how exactly. Los volcanes , the natives kept telling us. The volcanoes. But that didn’t make any sense. The only volcano I could see was miles and miles in the distance. I could only just make out its strange, flattened top, only just distinguish the trail of smoke that sometimes drifted from its ragged crater to blend with the mist hanging all around it. I didn’t understand how “volcanoes” could have turned the school wall to rubble.

But rubble is what it was when we got there. And the school hadn’t been much to begin with either. It was just a rectangular box made of cinder blocks with a long bench on each side for the kids to sit on, and a table and a blackboard up front for the teacher. Pretty pitiful when I compared it to my own school back home in California: Grove High, with its corridors and classrooms, its laboratories and library, its huge gym and football field and track and so on. Here in the Santiago cinder-block school, the kids barely had books to read and stuff to write with. Seriously: they used half pencils—pencils broken in half so there’d be enough to go around. They wrote on these little ragged notebooks, the blue covers nearly worn away, the pages full even at the borders because they had to use every inch of blank space they could find.

That’s what it was like when they went to school, but they couldn’t go much now with the wall demolished and one of the benches upside down on the floor amid the debris. Three cinder-block walls and a pile of gravel where the fourth one used to be—that was their schoolhouse now. Los volcanes . Whatever. We came to rebuild the place.

It was a church project. Or a church-slash-school project, to be more precise. The villagers here were too poor to buy the wall material themselves, and the local men were too busy working for their daily bread to take time to put the schoolhouse back together. So our church had taken up a collection for the cinder blocks and tools and mortar and so on, and then called for volunteers to come down here for a week or so during the summer break and slap the thing back up so the kids could get some kind of education. Grove High put up posters about the mission too, and Principal Hagen mentioned it during an assembly. In the end, some of us joined up in the name of Christian outreach and some of us came to get the Public Service credits we needed for graduation. Some of us had our own reasons too. Well, I guess all of us had our own reasons, when it comes down to it.

So who were we?

Well, let’s see, there was Pastor Ron, first of all. Ron Collins, the associate minister at our church. He was a small, thin guy, with a bland, friendly face, eyes blinking out from behind his thick dark-rimmed glasses. He was young, mild-mannered, enthusiastic. Maybe a little too enthusiastic sometimes, if you ask me. Trying too hard to make things exciting and interesting to his teenage traveling companions. You may know the type. Always wanting everyone to think everything was fun , fun , fun— and then getting sort of quietly disgruntled and annoyed when anyone thought it was not, not, not. But I don’t want to be unfair to him: he was a good guy, he really was. He always had time to listen to you and help you out if you had a problem. And his sermons were a lot more intelligent and interesting than the ones given by the head pastor, Pastor Francis. It’s just that Pastor Ron was sometimes a little bit… clueless , I guess you’d say.

Читать дальше