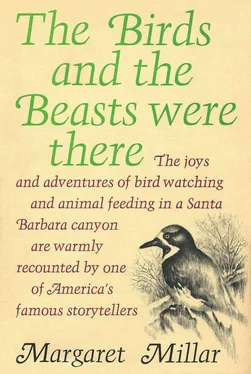

Маргарет Миллар - The Birds and the Beasts Were There

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Маргарет Миллар - The Birds and the Beasts Were There» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1967, Издательство: Random House, Жанр: Природа и животные, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Birds and the Beasts Were There

- Автор:

- Издательство:Random House

- Жанр:

- Год:1967

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Birds and the Beasts Were There: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Birds and the Beasts Were There»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Birds and the Beasts Were There — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Birds and the Beasts Were There», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The noise was deafening, most of it caused by the arrival and departure of helicopters and the shriek of sirens and blare of loudspeakers. The “helitack” units of the Forest Service consisted of the pilots themselves, the fire jumpers wearing heavy canvas suits to protect them when they leaped into the brush, and ground crews, in orange shirts and helmets, whose job was to prime and space the copters and keep them out of each other’s downdraft.

The scene, with its backdrop of blazing mountains, was unreal to me. Even the wounded men being brought in by helicopter looked like extras from the Warner Brothers back lot and the sirens of the ambulances as they left the field seemed like part of a sound track. The dogs knew better. They began to whine, so I let them out of the car and told them to go and find Ken. They didn’t hesitate. It was a good place to get away from.

Beyond the road leading into the firecamp was the top of our canyon. This part, which belonged to Westmont College and had no structures on it, had been completely burned. The ancient oak trees were black skeletons rising from grey ashes, and many eucalyptus, cypresses and Monterey pines had been reduced to stumps, some still smoldering. But where the row of houses began, along each side of the canyon, the burning had terminated. There was no evidence that the area had been wetted down nor any reddish stains indicating the use of fire retardant; no firebreak had been bulldozed and no hose laid. Yet at that one particular point the fire had stopped.

I learned later what had happened. At two-thirty in the morning, just when all hope of saving our canyon had been abandoned, the santana ceased as abruptly as it began and the wind pressed in from the sea, cool and moist. Temperatures dropped, humidity rose, and the flames were pushed back toward the mountains. It was during this lull that the Los Angeles Herald Examiner went to press with the front-page headlines “Santa Barbara Safe. Fire Shifts: 18 Homes Lost.” By the time I got to read those headlines Santa Barbara was surrounded on three sides by an inferno and a hundred more houses had been lost.

I stopped the car. Through the binoculars I kept in the glove compartment I examined hollows where smoke was still rising and stumps still smoldering unattended. At any moment they could burst into flames again and the santana could return. It had taken a miracle to save our canyon and there was probably only one to a customer. I rushed home to call the fire department.

Ken was asleep on the living-room davenport, a scribbled note on the coffee table beside him instructing me to wake him up when necessary. He didn’t stir even under the barrage of dog greetings.

Most of the telephones in the region were out of commission by this time. Ours was still working, though it failed to solve much. The fire department, I was told, had no trucks and no men available; people spotting areas which were still smoking were urged to cover them with dirt and/or douse them with water. I grabbed a shovel and a length of garden hose and headed back up the road.

During the windless morning the fire went through a semi-quiescent phase. There was unofficial talk of “early containment,” and a few evacuees began returning. Though the area where I was working still smoldered in places, other people had arrived to assist and the general picture looked good. By noon I felt secure enough to go home for some lunch. The only wildlife I’d seen all morning was an indignant family of acorn woodpeckers living in a nearby telephone pole, and a badly frightened and half-singed fox who came scurrying up from the bottom of the canyon.

Over tea and sandwiches Ken told me how he’d spent the night dousing sparks and embers that fell on the roof and in the underbrush. He had done his job well. Too well. The tea tree’s natural tendency to lean had been encouraged by the excessive water and it now lay on its side on the ground. Many trees were lost to fire during that week; our tea tree was probably the only one lost to flood.

We were finishing lunch when my sister called to tell us the fire had started on another rampage. By midafternoon the “early containment” theory had been blown sky high — and sky high turned out to be the precise description. The flames jumped El Camino Cielo, the sky road, and were racing down the other side of the ridge, with nothing whatever to stop them. Ten borate bombers were in operation, but dense smoke and wind conditions had grounded all of them and the fire roared unchecked into the back country, Santa Barbara’s vulnerable watershed.

El Camino Cielo was the road along the top of the first main ridge, starting at the east end of Montecito and continuing west past the city of Santa Barbara, San Marcos Pass, Santa Ynez Peak, its highest point at 4292 feet, and ending at Refugio Pass. Along this sky road, winter birdwatchers were apt to see mountain species which seldom appeared in the city itself — a Clark nutcracker noisily prying open the scales of a pine cone; a varied thrush standing in regal silence underneath a live oak, ignoring the raucous challenges of Steller jays; golden-crowned kinglets and brown creepers, mountain chickadees and red-breasted nuthatches, and sometimes a large garrulous flock of those erratic wanderers, the piñon jays.

The previous December, Jewell Kriger and I had done some advance scouting along Camino Cielo preparing for the Audubon Christmas bird count and we had come across a Townsend solitaire fly catching in the chamise and scrub oak along the sides of the road. A quarter of a mile beyond we found another solitaire. These birds are rarely found on a coastal bird count and we wanted to make sure that at least one of the solitaires would be located when the proper time arrived. Camino Cielo was not part of our regular territory — we were scouting it for Dr. Mary Erickson, ornithologist at the University of California at Santa Barbara. Mary was to head the group covering the area on actual count day, but she was too busy to do any preliminary looking.

The usual procedure in a situation like this was to note the mileage, and if the find was especially important, like the pygmy owls’ nest earlier in the year, to mark the spot with something that would attract attention without rousing the wrath of anti-litter-buggers. And others. (I mention “others” because on one occasion, to mark the whereabouts of a pair of black-chinned sparrows, I had carefully built a small mound out of stones, the best material on hand. Half our Audubon Society fell over the stones, and by the time the excitement subsided, the black-chinned sparrows were far away and glad of it.)

Near the pygmy owls’ nest we’d been lucky enough to pick up a good-sized piece of board painted red. We couldn’t expect such luck to be repeated, and it wasn’t. We found no marker in the area that would be readily visible from a moving car. Two more factors were against the Townsend solitaires appearing on our Christmas count. The speedometer on Jewell’s car was out of order and the previous weekend Russ Kriger had done one of his enthusiastic cleanup jobs on the car’s interior. A search through the glove compartment and the trunk, and even behind the seats, revealed nothing useable as a marker — no polishing cloth or chamois, no piece of rope or empty bottle, no last summer’s beach hat or last winter’s scarf. I looked at Jewell. She was wearing a white shirt and capris and a yellow sweater the exact shade of the band across the tip of a waxwing’s tail.

“Have you ever noticed,” I said, “how easy it is to identify a flock of cedar waxwings from a distance? The yellow tailbands show up very conspicuously.”

“So?”

“Experiments have shown that yellow is the color most easily seen from the greatest distance.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Birds and the Beasts Were There»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Birds and the Beasts Were There» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Birds and the Beasts Were There» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Маргарет Миллар - Rose's Last Summer [= The Lively Corpse]](/books/384369/margaret-millar-rose-s-last-summer-the-lively-c-thumb.webp)

![Маргарет Миллар - The Iron Gates [= Taste of Fears]](/books/433837/margaret-millar-the-iron-gates-taste-of-fears-thumb.webp)