By the beginning of 1974, it was starting to look as if our family was falling apart.

[FROM an interview with Harold Epstein.]

We live in a nation of ignoramuses. The average American knows nothing about science. A man asked me once if the stars went away when the sun rose, or if they were still there but you just couldn’t see them. He was a stockbroker I had the misfortune of employing, a man who made over one hundred thousand dollars a year! Well, I took my investments away from him, damn quick! And then the market climbed five hundred points. Oh well, that’s another story.

I do not begrudge the average American his ignorance. It’s a free country. But when you have elected officials, people who wield enormous power, who flaunt their ignorance, that is a different matter.

Senator William Proxmire was one of those people. Here we had a man of colossal ego and great power who was as ignorant as a — a poodle , who destroyed the scientific careers of many good people. Every year, the whole country would read about the Golden Fleece awards and laugh and snicker about these silly scientists with their absurd experiments. Now some experiments were trivial. It is a fact that most science is pedestrian. But Proxmire usually missed the real target — that is, faulty research — and demolished something important and worthy.

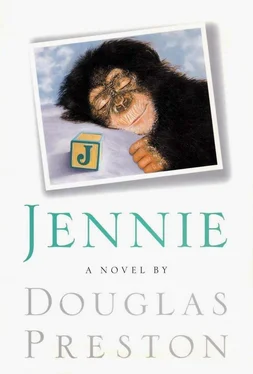

This was what happened to the Jennie project. Here we were, spending all this taxpayer money teaching chimps a few hundred signs. They had no clue as to how this would illuminate our understanding of human linguistic development. Or the evolution of language. Proxmire had no idea that this research might enhance the way we teach language to retarded or handicapped children. There was no understanding of the revolutionary results of our work, and how it revealed for the first time the mind of an ape — and how it helped us understand what it means to be human. No thought was given to what it would mean to be able to communicate for the first time with another species! No. It was framed as, “So, after half a million, what did the chimps say?” Well, not much, when you really analyze it. That wasn’t the point, for God’s sake! And the scientists who supported us were afraid to object. They didn’t want to attract Proxmire’s attention. Cowards, every one.

Anyway, going into 1974, things got very tough for Hugo and Lea. Hugo and I had had many discussions about what would happen when Jennie went into puberty. I was far more worried than Hugo. I tried to tell him that no family had ever kept a home-raised chimpanzee much past puberty. I emphasized that Jennie was not like a dog or cat, that she was a wild animal. Hugo didn’t believe it. He was optimistic and naive. He said that they had been through a lot with Jennie: They could weather anything. She was part of the family forever. He would never abandon her.

I pointed out to him that chimpanzees can live to be forty or fifty years old. Well, I said, who’s going to take care of Jennie after he and Lea became too old? Hugo sweated a little over that one but finally said that Sandy would probably take care of her. And what about Sandy’s future wife? I asked. How will she feel about a chimpanzee in the house? Had Sandy agreed to this?

Hugo then said that the problem was no different, say, than having a mentally retarded child. But (I pointed out) you can’t put Jennie in an institution. There are no social services for Jennie. She won’t qualify for governmental assistance, welfare, or Medicaid. She’s an animal, I said to Hugo. An animal. Was he financially able to create an endowed facility that would take care of Jennie for the rest of her life? Did he know how much principal it would take to yield, say, an income of one hundred thousand a year? Or was he going to put her in a zoo?

Hugo became defensive under this kind of questioning. Angry, even. He accused me of being a Cassandra, of always looking at the bad side. I hated to make him face these issues, but who else was going to do it? At least, I thought, Hugo will be somewhat prepared. Or so I hoped.

The inevitable happened. Jennie reached adolescence and went into estrus. Her whole personality changed. This was a very sudden change. Very sudden. While things had been worsening for a while, this was a whole new ball game. You know how traumatic it is when human children suddenly find themselves with these strange and powerful new feelings. It was worse for Jennie, operating on a foreign biology. Female chimpanzees are much more promiscuous than human females.

Hugo came into the museum, and almost every day I heard another disaster story. Jennie was running Lea ragged. Every week there was another uproar, another crisis. Meanwhile, Sandy, who had been a stabilizing force for Jennie, was slipping away from the family and becoming more involved in radical causes and going around with unsavory friends. He refused to consider college. He refused to take his SAT tests. Hugo and Lea were sick with worry. The sixties might have been over and Nixon gone, but there was still a lot of radicalism around in the early seventies. People have forgotten that the so-called sixties, as a political era, was really the period from about 1964 to 1974. Sandy came of age at the tail end of that era, but he rebelled just as thoroughly as if he’d been born five years earlier.

I’m getting off the subject. I remember one morning Hugo came into my office, looking haggard. He had not slept at all the night before. Jennie, he said, had refused to go to her room for the night. It had proved physically impossible to force her. You understand, although she weighed only seventy pounds, she was five times stronger than a grown man.

They tried everything. They tried coaxing her with food. They snapped a lead on her and tried to drag her in. They signed to her until they were blue in the face. She had learned a sign from somewhere, an obscene gesture. The middle finger extended. You know what I mean. She started using the finger almost continuously in lieu of other signs. She used it to frustrate any attempt to communicate with her. You’d sign Jennie be quiet and she’d jab her hand in the air with her middle finger extended! It was outrageous! You’d say No bad Jennie! and she’d stick her finger right in your face. Imagine that! I saw this on several visits to the house. Anyway, getting back to this particular night. They finally gave up and tried to go to bed, leaving her outside. But she started running around the house, breaking things and knocking over the refrigerator. They spent all night trying to control her.

When Hugo finished telling me this story, he put his head in his hands and he broke down and wept. I was... I was quite taken aback. I was shocked. I had no idea just how far things had gone. He told me that this wasn’t the first time this had happened, and what was he going to do? We talked and talked and Hugo finally said, “Here we are, two of the world’s experts on chimpanzee behavior, and we have no idea how to control this one animal.” And he laughed bitterly. For the first time in my life I felt at a total loss. I had no idea what to do, no answer for him. I felt only dread for what the future might hold.

And then, later that year — well, did you know that Sandy and Jennie had an upset, a — No? They had a disagreement, an upset... I’d rather not discuss it. In fact, I don’t really know what happened. I really don’t. You’ll have to talk to Lea Archibald about that.

[FROM the journals of the Rev. Hendricks Palliser.]

October 28, 1973

Last Sunday I delivered a particularly good sermon — I ask God’s forgiveness for the sin of pride — on the guilt and suffering of Judas Escariot. I do not believe, however, that the congregation took to it. I asked the question: Was Judas chosen for the deed? It was prophesied, was it not? Where, then, is the guilt? But I muddled the answer. The good people of Kibbencook, indeed all human beings, want answers, not questions, from their religious leaders. No matter.

Читать дальше