He shopped at a store on the mainland once a month. One month he did not appear. When he failed to show up the following month, some locals went to the island to see if he needed help or was sick. They found his boat, carefully pulled up on the beach, his bed made, canned goods stacked in a corner, clothes folded in a trunk. There was no sign of him, and he was never seen again. He had completely disappeared.

Some said he was caught in an undertow while taking a morning swim, while others said he inherited money and went to Boston. He had no family and title to the island was eventually acquired by the state of Maine.

The odd thing about it, or so the locals said, was that Tundish had been posted well behind the front and had never seen combat. Shell shock or the horrors of war were not the reason for his silence. The townsfolk had no explanation for what had happened to him, except to nod and say, “Well now, they was all a little crazy in that family.”

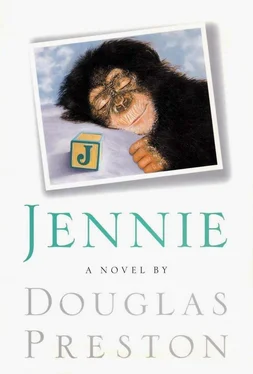

When we camped on the island, we sometimes took the boat out in the afternoon to catch a dinner of fresh mackerel. The first time we went fishing, Jennie watched intently the preparations, but when the first flapping fish was hauled in she screamed and dove under the seat. She soon got over her fright, and one day we let Jennie take the rod. Almost immediately she had a strike. Sandy hollered “Reel it in!” but at first Jennie was so excited all she could do was scream and hop up and down while the rod jerked and twitched. We finally got her reeling it in, and when the fish arrived she was beside herself with excitement. She grabbed it and banged it on the bottom of the boat and slapped and stomped on it. Jennie had seen us killing and cleaning fish, and this was her way of helping out. As soon as the fish was safely in the creel she started signing frantically Fish! Fish! and grabbing at the rod. She became a true fanatic.

Jennie reeled in one mackerel after another. It was a good year for mackerel and one could be certain of catching a fish by dropping a line in the water and trolling for a few minutes. As much as she liked to catch them, once they were dead she lost all interest in them, and she did not relish eating them. When we fried them up for dinner she made terrible grimacing faces at the smell and often moved as far away from the fireplace as she could.

She slept curled up in her blanket against Sandy in his sleeping bag. Lea took a photograph of them one morning as the light came in the cabin windows, a photograph which is now framed in my office. Sandy’s long hair is sticking out in all directions, and his mouth is open and drool is on the pillow, just like a little boy. All his radical trappings seem stripped away, leaving his innocence. Jennie lies next to him with her arm thrown around his shoulder and a look of deep contentment on her brown face. When I look at that picture I can still hear the gulls crying outside, the sound of the surf, and the smell of seaweed and salt air coming in through the broken window frames. It was a magical summer.

On a visit to the island near the end of the summer, Sandy made an extraordinary discovery. He was cleaning out the fireplace (under protest) and he discovered a loose stone in the back. He pulled it out and found a secret hiding place. In the hiding place was a small, hexagonal wooden box.

He called us all inside and we watched him open it up. We were hoping for South Sea jewels or a stack of gold doubloons, but instead the lid crumbled in his hand, revealing a long letter and a bundle of photographs. Folded up in a piece of paper were a Morgan head silver dollar and a blue turquoise bead.

We were disappointed when we inspected our treasure. The photographs were completely ruined by time, water, and rot. One could see nothing. The letter, also, had rotted and the pages stuck together. Furthermore, the ink had been leached out by rain coming down the chimney. The silver dollar and the bead were the only items relatively unscathed by time. Sandy kept the silver dollar, but I do not know what happened to the rest.

After Labor Day we returned to Kibbencook. That was when Dr. Prentiss regretfully informed us that she could no longer tutor Jennie. Jennie had been very fond of Dr. Prentiss, and she took her departure hard, waiting on the appropriate days for her car, sulking all day long.

The most difficult change was yet to come. In October or November, Jennie went into estrus for the first time. This was not a full-blown estrus, but an early, pubescent version. Female chimpanzees, when they cycle, show a dramatic change in their genital region, which swells up and becomes pink. The sexual impulses of a female chimpanzee in heat are far more powerful than those of a human.

Jennie did not understand what was happening to her and had no idea how to deal with it. During this first estrus, she became restless and almost impossible to control. She acted in ways that were embarrassing and socially inappropriate. She became particularly irritable toward me and Sandy. She would not allow us to approach her, let alone touch her, and she often broke into loud screams if we approached. She also became curiously incommunicative and ignored many of our efforts to sign to her. Lea and I knew well that chimpanzees become difficult when they reach puberty. And yet, we had managed to persuade ourselves that Jennie would be different. We felt we knew Jennie even better than we knew each other. We were wrong.

While in estrus she found being confined intolerable, even though she had always slept in a locked room. We had to listen to her screaming and pounding much of the night, and one night during that first estrus she managed to break the lock and get out.

She wrought havoc in the kitchen, and even overturned the refrigerator in her efforts to wrench off the padlock. We had to hire a man to build a steel door to her room and put bars on the windows. We hated to see her room turned into a cage, but there seemed to be no alternative. We did not want her to hurt herself or anyone else.

During estrus Jennie also became incontinent. She seemed to have trouble retaining her urine, or for some behavioral reason she began urinating in various rooms of the house. Harold Epstein, Dr. Prentiss, and I consulted on this, but we could find no research on chimpanzees that indicated how or why this kind of problem might have occurred.

Up to this point, Sandy and Jennie had a true sibling friendship. Jennie’s cycling disrupted even this. She lost interest in being around Sandy, ceased to obey him, and became irritated when he tried to play with her. Sandy was sixteen and Jennie’s behavior angered and puzzled him. Sixteen-year-old boys are often quite inflexible in the way they relate to others, and Sandy could not understand that it was a natural change in Jennie. It caused a minor estrangement between them, and Sandy began going out without Jennie.

All this had one unfortunate result: it threw a great burden on Lea’s shoulders. Jennie could no longer come to the museum; she could no longer spend time with Dr. Prentiss; and she was going out less with Sandy. Instead, she stayed at home all day, fretted, grumped, and got into trouble. For her own sanity Lea was forced to lock Jennie in her room for hours at a time, where the chimp screamed and carried on. We even had to discontinue Jennie’s visits to the old Reverend Palliser’s house. Palliser had become increasingly forgetful, and we feared for his safety. Jennie was wild.

When she came out of that first estrus, her personality did not entirely return to normal, although things settled down. There were still cool relations between Sandy and Jennie. Several months later she cycled again and the difficult period started all over, only worse. I was being called home from the museum by Lea again and again to handle one crisis after another. My work was suffering badly. Sarah found Jennie’s presence even more odious, and she began spending inordinate amounts of time at a friend’s house.

Читать дальше