Well, she finally got it working on the driveway, and Sandy showed her how to steer. And then Sandy got out his bike, and the two of them went riding off into the sunset.

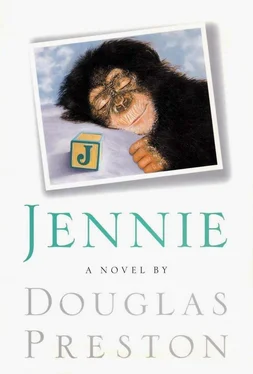

Anyway, that was how Jennie acquired her famous trike.

[FROM the journal of the Rev. Hendricks Palliser.]

October 25, 1965

A chill wind out of the northeast removed the last leaves from the birch. I watched the last one flutter and carouse in the gray morning light, and it filled me with thoughts of God. The clouds thickened at midday, a dreary rain began to fall, and the fog of the season closed over the brook. The garden in the back, with its vacant beds, the cherry tree blackened by rain and stripped of its leaves, the damp turf matted and brown, all reminded me of the great system of life and death. I opened the study window and breathed in the damp air. It smelled cold, but pregnant with dormant life, and it was a wonderful smell — truly a gift from God. And it also reminded me, in a peculiar way, of those still mornings in Belgium, before dawn, when the mist rose from the fields, so beautiful, just before the sounding of the artillery.

I thought that we are like the last leaf of autumn, the matted grass, the sleeping tree — all part of some great invisible plan, a plan as incomprehensible to us as the cycle of seasons is to the fallen autumn leaf. Perhaps, as the cells of the leaf freeze and turn glorious color and die, the leaf does suffer in a dim way. But the leaf, as it blazes its last glory, can no more know the source of its suffering than we can. Thus we human beings suffer for the glory of God, and know not whence the suffering comes, or why.

It is a powerful image. I shall work it into a sermon someday.

I continued laboring over Sunday’s sermon until lunch, sketching out the main idea. I’ve called it “Predestination and Postum.” The thought I am developing is how one goes about integrating the mystical side of Protestant Christianity with quotidien living. My church suffers from being too prosaic. We lack a sense of the mystical, the unknowable, the ineffable. When I walk to the pulpit on a Sunday and see my parishioners seated so properly in their rows, so neatly dressed, so assured and expectant, I am filled with a sense of panic. I have not done what I set out to do. In forty years, what have I given these people? Only a sense of complacency?

I am not satisfied with the title. “Predestination and Porridge”? They both have a bathetic sound. I am not, I regret, very facile with words.

This all leads me to an extraordinary occurrence that happened this day. For some days now, at three o’clock, the boy Sandy from across the street has come riding past on his bicycle with the monkey in hot pursuit on a tricycle. The professor must be training her for an act of some kind. They generally head down to the brook path and thence into the park.

As they passed the house, where the street slopes downhill, the poor monkey lost control of her tricycle and ran up on the lawn before ending up in a heap. I heard the most heartbreaking sound coming from her, so I rushed out to help. I bent over her, not quite knowing what to do. The poor thing held up her arms to me! And allowed me to pick her up! She hugged me in a most endearing way. She was terribly distressed.

Without even thinking, I invited them inside for comforting, cookies, and milk. I dabbed some Mercurochrome on the animal’s knee, and she set up a loud whimpering. R. came downstairs from her afternoon nap. “What is all this caterwauling?” she said, etc., etc. Not an altogether felicitous scene followed, but mitigated by the presence of the Archibald child. But the dear little animal is so captivating that even R. was softened. She even went into the kitchen and fetched cookies and milk.

Jennie and Sandy sat at the breakfast table, the chimp with her hands folded on the tabletop and her bright happy curious eyes darting about. When the cookies came she took one as polite as you please, from the correct (i.e., near) side of the dish. She nibbled it daintily while Sandy grubbed about with dirty hands looking for the three or four biggest, cramming one after the other into his mouth. The contrast was amusing and not lost on R. Indeed, R. was speechless. Jennie drank the milk with a rather unpleasant sucking noise and when she lowered the glass her muzzle was dripping, but then she politely wiped her mouth with the napkin and so all was well. Sandy wiped his mouth with his hand, and not — I might add — before wiping his nose.

Jennie was wearing the hat. I had an uncomfortable moment when R. remarked on what a peculiar hat the ape was sporting. But I needn’t have worried. The hat was much altered. It was quite dreadful and unsanitary, and Jennie did not remove the hat at the table. Her manners still need work. The professor and his wife, I hasten to add, would do well to start with Sandy, however, whose lack of the finer graces is appalling.

I made a grave error in referring to Jennie as a monkey; Sandy was quick to inform me that she is an ape , that monkeys are a much lower form of primate, and that any such reference to Jennie was as insulting as it was inaccurate. And apparently, she is with the family for good.

I watched Jennie as she ate. I had not forgotten my earlier feelings about the animal. She seemed so alert and intelligent that I once again wondered whether she could possibly comprehend the love of God, and the love of Jesus Christ. As children do, through feeling, pictures, and story, rather than ratiocination.

When Jennie finished her cookie and milk, she sat back in her chair and in the satisfaction of the moment she looked right at me. There was a flicker of something — a flicker of that questioning, wondering, hoping, seeking? It was that mysterious self-awareness that I see in the eyes of children as they start to understand the world. That questioning is the first step to God. Then the chimp laid her hand on mine! It seemed a kind of thank-you for my help. A brief, warm touch full of affection, while she looked at me with those eyes , as if she wished to ask something of me. It was a gesture of kindness that bridged the chasm between Man and Beast, a gesture which effaced millions of years of evolution. For the pressure of her fingers spoke to me not through the intellect but through the heart. It was a universal gesture of love, and in the electricity of that touch, I knew that Jennie had a soul. My question had been answered.

Sandy took Jennie’s hand and they rose to go. I quickly asked them to stay for a moment, while I went into my study without really thinking what I was doing, knowing only that I desired to give Jennie something. There I found a silver Mexican crucifix on a chain, given to me by Henry Cruikshank after his dear wife’s funeral. It is a lovely little hammered cross, intricately chased and decorated.

When I came to the foyer, Jennie looked up at me. I kneeled in front of her with my hands behind my back. “I’ve got a present for you,” I said. I don’t know whether she understood the words, but she stretched out her hand readily enough. I gave her the crucifix and she immediately inserted it in her mouth! I gently removed it and draped it around her neck. She picked it up and gazed at it, sniffed it, tasted it with her tongue, turned it around and around. Such fascination! I watched her with great care, thinking she would try to swallow it. Finally she let it drop and Sandy and Jennie departed.

I later found a lovely picture of the Baby Jesus that I will give Jennie on her next visit.

I have reached a curious resolution. There are many who would ridicule the idea. I am now resolved to see what I can do to help this animal experience the love of God. As I write this, seeing in my mind’s eye those alert black eyes, I cannot help but think that the chimpanzee has a mind capable of understanding the love of God. For love is an emotion present across the animal kingdom, and combined even with a modicum of intellect can grow from the instinctual love between beasts to a higher love of the ineffable.

Читать дальше