Both groups re-formed like schooling fish, but this time with no gap between us, united by the experience. Most people were laughing, a common response to shock, led by Eric who was delighted by the encounter. I was chuckling away too, but warily eyed the commando for a few tense seconds before Eric said it was too crowded and we should move on.

I waited for a voice to call me back or a sucker punch to the back of my head, but we returned to our canoe without incident. This made me wonder if the commando had considered his sins and felt some shame, or whether he was mellower than I had given him credit for, or merely dulled by dope.

While I accepted that diplomacy might be the better approach in future, all I knew was that I had stood up for something that mattered to me. I probably hadn’t taught him anything—in fact, he undoubtedly respected my stand as much as a pigeon respects a statue. Nevertheless, I felt a small sense of pride from the experience, even if it had taken an oversized guinea pig to save me.

The Idiot Box

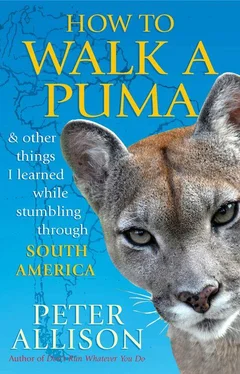

Over the years I’d been approached several times by producers who’d read my books about safari guiding in Africa and who were interested in making a TV show based on them. While these opportunities had all dried up, I received a new approach while I was travelling in South America which felt different, like we might make something worthwhile, in contrast to the current crop of wildlife shows which all seemed to involve the host diving onto animals then proclaiming, ‘He seems a bit agitated,’ as the creature struggles to get free. Despite myself, I started getting excited that we could make a show that was based on information and conservation.

Back in Australia the occasional day’s test filming had led to adventures like being locked in a cage with white lions—a welcome escape from my office routine and a reminder of what I was passionate about. Though the concept of being on television caused some mixed feelings, since I cherish the relative anonymity of being an author, there were some good reasons to be enthusiastic this time. The production company told me that one of their priorities was highlighting issues of conservation. If it worked out, presenting a TV show would also fulfil my desire to continue travelling the world watching animals, and would pay far better than writing alone.

After our boating adventures, the Minke and I had decided to travel further north, and when the production company wanted to do a test shoot we agreed that the best place to meet was Colombia.

‘Is it really safe here?’ Michael asked. He would be producer, director and cameraman for the shoot, and had just landed at Bogotá airport. He was referring to the country’s violent reputation as a hotbed for criminal activities run by drug lords. Lisa and I had already spent two weeks travelling through some of its towns and coffee-growing regions and had found them nothing but charming.

‘Seems it,’ I replied, and that was true as far as our experiences went.

Lisa didn’t care to accompany us for the test shoot, and went head alone to Cartagena, a Spanish colonial city on the Caribbean coast, where I intended to join her three days later. I wasn’t perturbed at the thought of her travelling alone because of how safe the country felt, and because she was more than savvy enough to go alone—in fact had done so for several months before we had met. Also, I would back her in a bar fight any day.

‘It seems very safe,’ I reassured Michael, who still seemed nervous.

He might have had a point. I’d arranged a naturalist guide to accompany us, but we were heading into more remote parts of the country, and there might still be rebel activity in these areas. And as well as the guerrilla groups, over the next two days of travel there was a chance we’d encounter pumas, bears, snakes and maybe, just maybe, a jaguar.

On the first day of travelling together, Michael and I were met in front of our hotel at the foul hour of four am by our guide, Diana, and a man named Eduardo who would act as our driver. From the look of his shaved head and bulging muscles he was likely to be talented at security too. His car was tiny, its tyres no larger than dinner plates. He squeezed his massive frame behind the wheel with difficulty, and drove with an arm out the window by necessity as much as attitude.

Bogotá is the world’s second-highest capital city (after La Paz in Bolivia), but Eduardo drove us higher still, up and up. We passed panting cyclists struggling in the thin air, and I found the mere idea of exertion in this oxygen-depleted part of the world tiring.

After several hours’ drive, and a break to partake of a local energy brew that consisted of hot water, huge chunks of palm sugar and a slab of rubbery white cheese, we reached Chingaza National Park, accessible only by special permission. The power a TV camera can wield became apparent, as the guards checking our papers were more interested in whether we were famous than if everything was in order.

After completing security we drove through gates into a place of clear streams and tussock grasses, as well as alien-looking plants with hairy leaves on dead-straight stems. Everything glistened with dew and our breath fogged with each exhalation. This habitat, called páramo, consisted of high-altitude wetland that was home to rarely seen species such as the mountain tapir, as well as more cosmopolitan animals like pumas and the continent-spanning white-tailed deer.

‘More energy!’ Michael called as I was doing my first piece to camera.

Whenever animals are the subject of general conversation I become very animated, and could flap my jaw at the person I’m talking to until their ears bleed. But talking to a camera is very different; addressing the lidless eye of the lens and the slow-blinking red light above I found it hard to muster anything more than a dull monotone.

‘Páramo,’ I said blandly, ‘is high. Cold. Wet.’

‘More energy!’ Michael called again.

I remembered all the wildlife television hosts I’d seen over the years, bounding over rocks like mountain goats, jumping on animals, going into raptures at any critter they encountered. To show that I wasn’t beyond such lunacy myself, I came up with the idea of sampling a plant, unwise given that my knowledge of local botany was negligible. Maybe, though, some plant compound could give me the manic energy I needed to cut it on film. I skipped the unappealing hairy plant and spied something that looked a little like rosemary. My taste test revealed it to be something you’d never add to a meal. As I spat out the bitter pith, Michael said, ‘Great! Let’s get some more of that!’

Diana directed Eduardo to drive us to likely habitats for pumas and other species, while Michael encouraged me to shout and gesticulate wildly for the camera, making so much noise that any sensible cat would emigrate in protest.

‘Look at this!’ I yelled, pointing at a pile of bones I’d found after climbing onto a small ledge.

Michael followed, slipping and sliding on the mossy rocks as he continued filming. I have long ago given up the idea of athletic prowess or even sure-footedness, and consider any day that I don’t fall over or walk into anything a victory, but Michael was so out of his element in the wilderness that I felt like a ballerina. Gasping for breath, he joined me.

‘Puma kill!’ I said, genuinely excited now. Attached to the bones were some withered strips of sinew, skin turning to leather and a foot. ‘See this! Not a hoof … looks like it was a fox!’ I enjoy playing wildlife detective so I was grinning in genuine delight as I checked the carcass’s surrounds and located the distinct pugmarks of a puma, still familiar from my time with Roy. ‘Yes! Definitely a puma kill—not so fresh, maybe even a week or more old, but the overhang has protected the tracks from rain. Nice!’

Читать дальше