I was wondering if I could keep these insects alive in a netting cage on a diet of honey and water, and so get them back to England, when Elias returned. He had discovered the path, he said, and now knew where he was.

We rejoined the path and resumed our way towards the grass field. These grass fields are formed in certain areas of the forest where the soil is too shallow to support the probing roots of the huge trees. A low clinging growth covers this space, a growth that can exist with its wiry roots clinging to the few inches of soil covering the great carapace of rock that forms the foundation to the forest. So the tough grasses come into their own, spreading across the clearing; in the cracks in the rocks, where the rains have washed the soil into deeper pockets, tiny stunted trees get a foothold and flourish. But these small fields are ringed about by the tall forest: should the depth of soil increase the great trees scatter their seed and slowly usurp this territory from the grip of this lowly vegetation.

Presently the trees grew thinner, the light grew stronger, and we came to a thick tangle of low growth that bordered the clearing. We pushed our way through this flower-hung, thorny curtain, and found ourselves knee-deep in long grass, the clearing sloping away from us like a great meadow, golden-green in the sun, quiet and lonely, its borders fringed with the towering ramparts of the forest.

We lay down in the warm crisp grass and lit cigarettes. We lay there, basking in the sun, and gradually the sounds of the life in the clearing came floating to us: the ringing cries of the big pink winged locusts; a tree frog piping shrilly from the banks of the tiny trickle of water that curled through the grass; the soft and husky coo of a small dove, perched in the bushes above us. Then, from the far side of the clearing, a series of loud care-free cries rang out, echoing among the trees: “Carroo . . . carroo . . . coo . . . coo . . . coo. . . .”

Again and again, echoing loud across the shimmering grass. I trained my field-glasses on to the trees at the far side of the clearing and searched the branches carefully. Then I saw them, three large glittering green birds, with long heavy tails and curved crests. They took flight, straight as arrows, across the clearing, and landed in the trees the opposite side, and as they landed they shouted their challenging cry again. As they called, as though in an excess of high spirits, they leapt from branch to branch in great rabbit-like leaps, and raced along the branches like racehorses, as easily as though the branches had been roads. They were a flock of Giant Plantain-eaters, perhaps the most beautiful of the forest birds. I had often heard their wild cries in the forest, but this was my first sight of them. Their acrobatic powers amazed me, as they leapt and bounded, and ran amongst the branches, pausing now and then to pluck a fruit and swallow it, and then shout to the forest. As they flew from tree to tree in the sun, trailing their tails behind them like giant magpies, they shimmered green and gold, a breathtakingly beautiful colour.

“Elias, you see those birds?”

“Yessir.”

“I go give ten shillings for one of those alive.”

“Na true, sah?” “Na true. So you go try, eh?”

“Yessir . . . ten shillings . . . eh . . . aehh!” said Elias, as he lay back in the grass to enjoy the last puffs of his cigarette.

I sat back and watched the gorgeous shining birds leap and twist their way into the maze of trees, shouting joyfully to each other, and then silence descended on the grass field again.

Presently we set to work. The long nets with the small mesh were unpacked, and these we arranged in a half-circle, the lower edge buried in the soil. They were hung rather loosely, so that any animal running into them would become entangled in the folds. Then, from point to point of the nets, we cleared the undergrowth away in a strip some two feet wide, and, cutting grass, we laid this along the line, and covered it lightly with damp leaf-mould. Now we had a complete circle, half formed by the nets, the other half by this line of dry grass. Then we proceeded to drench the grass with kerosene and set light to it. The damp leaf-mould prevented the tinder-like grass from burning quickly, so it smouldered gently, letting a thin curtain of pungent smoke drift towards the nets. We waited expectantly, but nothing happened. Only a host of big locusts fled from the smoke, hopping and whirring agitatedly. We put out the fire, moved the nets to a fresh area, and repeated the performance with the same results. Our eyes smarted with the smoke, and we were scorched by the fire and the sun. Six times we moved the nets, laboriously laid the fires, and still caught nothing for our pains.

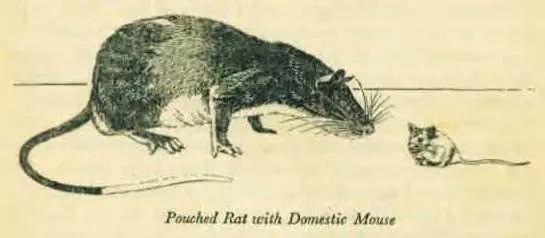

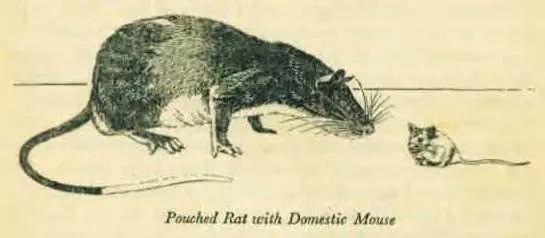

I was beginning to doubt Elias’s judgement of this grass field as a good place for beef, when on the seventh pitch we struck lucky. Scarcely had we set fire to the grass when I saw a portion of the net start to quiver and jerk. I rushed through the smoke and found a large grey animal with a long scaly tail struggling in the folds of the net. I caught him swiftly by the tail and swung him aloft: it was a Pouched Rat, as big as a kitten, his grey fur full of the large cockroach-like parasites that inhabit these beasts.

“Elias, I get ground beef,” I shouted. But he was too busy at another part of the net to heed me, so with some difficulty I succeeded in getting the rat into a thick canvas bag without getting myself bitten. I approached the other end of the net through the smoke, and found Elias darting about on all fours grunting and mumbling angrily:

“Ah, you blurry ting you . . . ah, you bad beef. . . ”

“What is it, Elias?”

“Na bush rat, sah,” he said excitedly, “’e de run too fast, and ’e de bite too much . . . careful, sah, ’e go chop you. . . ”

In and out of the tussocks of grass ran a host of rats, dancing and jumping with speed and agility, retreating before the smoke, yet avoiding the mesh of the net with extraordinary efficiency. They were fat and sleek, with olive-green bodies, and their noses and behinds were a bright rusty red. They ran through our legs, leapt in and out of the grass, their little pink paws working overtime, and their long white whiskers twitching nervously. They were quite fearless, and they bit like demons. As Elias knelt down to try and catch one in the grass, another ran up his leg, burrowed rapidly under his loin-cloth, and bit him in the groin. It dropped to the ground and disappeared into the grass.

“Arrrrr!” roared Elias. “’E done chop me, sah . . . eh aehh! Na bad beef dis ting. . . .”

But one had just fastened its teeth into my thumb, so I was too occupied to take much interest in Elias’s honourable wounds. In the end we captured ten of these rats, and emerged from the smoke looking as though we had been having a rough and tumble with a leopard. I had five painful bites on my hands, and my face was scratched where I had fallen into a large and evil bush. Elias’s legs were streaming with blood and he had two bites on his hands and one on his knee. It is astonishing how one bleeds in the tropics: the slightest scratch and the blood flows out freely as though you had severed an artery. Our sweat was trickling into these open bites and scratches and making them smart furiously. Our hair was full of mud and ashes. I decided that the rats had made us pay dearly for their capture.

We decided to smoke one more patch of grass before starting for home. The tedious business of setting up the nets and laying the fires we now performed cheerfully, for the captures had elated us, as captures of any sort always did. There is nothing so depressing as repeating a thing over and over again with no results. We stood back expectantly and watched the smoke curl sluggishly into the golden grass.

Читать дальше