The monkey in the tree above me was presumably the leader, for he was a male of huge proportions. Having surveyed the forest below the cliff and seen no danger, he had uttered his “all clear” cry to the rest of the troop, and then he leapt from his bush above me and plummeted downwards like a stone over the edge of the cliff, hands and legs outstretched, to land among the top branches of a tree-top just opposite to where I was lying. He disappeared among the leaves for a few seconds, and then reappeared walking along a branch. When he reached a comfortable fork he seated himself, looked about him, and uttered a few deep grunts.

Immediately the bush above me swayed and shook as another monkey landed in it, and almost in the same movement leapt off again to drop down over the cliff into the tree-top where the old male was waiting. Their progression was very orderly: as one landed in the tree below another would arrive in the bush above me. I counted thirty adults as they jumped, and many of the females had young clinging to their bodies. I could hear these babies giving shrill squeaks, either of fear or delight, as their parents hurtled downwards. When the whole troop was installed in the tree they spread out and started to feed on a small black fruit that was growing there. They walked along the branches, plucking the fruit and stuffing it into their mouths, continuously glancing a-round them in the quick nervous way that all monkeys have. Some of the bigger babies had now unhooked themselves from their mothers’ fur and followed them through the trees uttering their plaintive cries of “Weeek! . . . Weeek!” in shrill, quavering voices. The adults exchanged comments in deep grunts. I saw no fights break out; occasionally a particularly fine fruit would be snatched by one monkey from the paws of a smaller individual, but beyond a yarring grunt of indignation from the victim, nothing happened to disturb their peaceful feeding.

Suddenly there was a great harsh swishing of wind and a series of wild honking cries as two hornbills flew up from the forest below, and with the air of drunken imbecility common to their kind crashed to rest among the branches, in the noisy unbalanced way that is the hornbill’s idea of a perfect landing. They clung to the branches, blinking delightedly at the Monas from under the great swollen casques that ornamented their heads, like elongated balloons. Then they hopped crabwise along the branches and plucked the black fruit with the tips of their beaks most delicately. Then they would throw back their heads and toss the fruit down their throats. After each gulp they would squat and stare roguishly at the monkeys from their great black eyes, fluttering their heavy eyelashes. The Monas ignored these tattered clowns with their Cyrano de Bergerac profiles, and continued to feed quietly. They were used to hornbills, for what the vulture is to the lion, the hornbill is to the monkeys in the Cameroons. Whenever there is a troop of monkeys feeding, there, sooner or later, you will find some hornbills, giving the whole position away with their loud honking and the swish of their wings, which can be heard a mile away. How the monkeys must have hated the company of these great birds, and yet they had to suffer it.

Presently the hornbills flew off with a great thrashing of wings, and soon after the leader of the Monas decided that it was time they were moving. He grunted a few times, and the mothers clasped their young to their bellies, and then they leapt, one by one, down into the foliage below, and were swallowed up in a sea of leaves. For some little time I could hear their progress through the forest below, the surging crash of leaves as they jumped from tree to tree sounding like slow heavy breakers on a rocky shore. When I could no longer hear them I rose from my hiding place, cramped and stiff, picked the twigs and the ants from my person, and blundered my way back to camp through the darkening forest.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

THE JU-JU THAT WORKED

THE next two days were spent hunting with the dogs, and we had exceptionally good luck. The first day we caught a young Monitor and a full-grown Duiker, but it was on the second day that we secured a real prize. We had spent some hours rushing madly up and down the mountain following the dogs, who were following trails that seemed to lead nowhere, and at length we had halted for a rest among some huge boulders. We squatted on the rocks, gasping and sweating, while our dauntless pack lay at our feet, limp and panting. Soon, when we had all regained our breath somewhat, one of the dogs got up and wandered off into some neighbouring bushes, where we could hear it sniffing around, its bell clonking. Suddenly it let out a wild yelp, and we could hear it rushing off through the bushes; immediately the rest of the pack was galvanized into action and followed quickly with much yelping. We gathered up our things hastily, flung away our half smoked cigarettes, and followed the pack with all speed. At first the trail led downhill, and we leapt wildly among the boulders and roots as we rushed down the steep incline. At one point there was a flimsy sapling hanging low over our path, and instead of ducking beneath it as the others had done, I brushed it aside with one hand. Immediately a swarm of black dots appeared before my eyes and an agonizing pain spread over my neck and cheek. On the branch which I had so carelessly thrust aside there was hanging a small forest wasps’ nest, a thing the size of an apple hanging concealed beneath the leaves. The owners of these nests are swift and angry, and do not hesitate to attack, as I now realized. As I rushed on, clutching my cheek and neck and cursing fluently, it occurred to me that the hunters had seen the nest and had instinctively ducked to avoid disturbing it, and they presumably thought I would do the same. From then on I imitated their actions slavishly, while my head ached and throbbed.

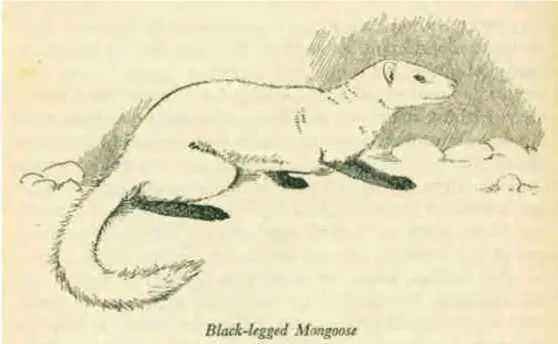

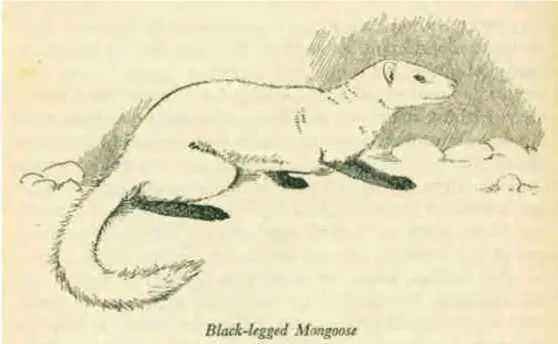

It was the longest chase we had had to date; we must have run for nearly an hour, and towards the end I was so exhausted and in such pain that I did not really care if we captured anything or not. But eventually we caught up with the pack, and we found them grouped around the end of a great hollow tree trunk thaat stretched across the forest floor. The sight of the animal that crouched snarling gently at the dogs in the mouth of the trunk revived my interest in life immediately; it was the size of an English fox, with a heavy, rather bear-like face, and neat round ears. Its long sinuous body was cream coloured, as were its head and tail. Its slim and delicate legs were chocolate brown. It was a Black-legged Mongoose, probably the rarest of the mongoose family in West Africa. On our arrival this rarity cast us a scornful glance and retreated into the interior of the trunk, and as soon as he had disappeared the dogs regained their courage and flung themselves at the opening and hurled abuse at him, though none of them, I noticed, tried to follow him.

The hunters now noticed for the first time that I had been stung, for my face and neck were swollen, and one eye was half closed in what must have looked like a rather lascivious wink. They stood around me moaning and clicking their fingers with grief, and ejaculating “Sorry, sah!” at intervals, while the Tailor rushed off to a nearby stream and brought me water to wash the stings with. Application of a cold compress eased the pain considerably, and we then set about the task of routing the Mongoose from his stronghold. Luckily the tree was an old one, and under the crust of bark we found the wood dry and easy to cut. We laid nets over the mouth of the trunk, and then at the other end we cut a small hole and in this we laid a fire of green twigs and leaves. This was lit and the Tailor, armed with a great bunch of leaves, fanned it vigorously so that the smoke was blown along the hollow belly of the dead tree. As we added more and more green fuel to the fire, and the smoke became thicker and more pungent, we could hear the Mongoose coughing angrily inside the trunk. Soon it became too much for him, and he shot out into the nets in a cloud of smoke, like a small white cannon-ball from the mouth of a very large cannon. It took us a long time to unwind him, for he had tied himself up most intricately, but at last we got him into a canvas bag, and set off for camp, tired but in high spirits. Even the pain of my wasp stings was forgotten in the warm glow of triumph that enveloped me.

Читать дальше