We left the river and returned to the road, and remounted the bicycle which, by now, I was beginning to dislike intensely. I pounded miserably onwards, feeling the dust settling once more on my body and clothes.

Half an hour later we were free-wheeling down a long gentle incline, when I saw a figure in the distance marching towards us. As we drew closer I saw that the man was carrying a small basket fashioned out of green palm leaves, a sure sign that he was bringing an animal to sell.

“Dat man get beef; Daniel?” I asked, putting on the brakes.

“I tink so, sah.”

The man came padding along the dusty road, and as he drew closer he doffed his cap and grinned, and I recognized him as an Eshobi hunter.

“Welcome,” I called. “You done come?”

“Morning, sah!” he answered, holding out his green basket. “I done bring beef for Masa.”

“Well, I hope it’s good beef,” I said, as I took it, “or else you’ve walked a long way for nothing.”

Daniel and the hunter shook hands and chattered away in Banyangi while I undid the mouth of the basket and peered inside.

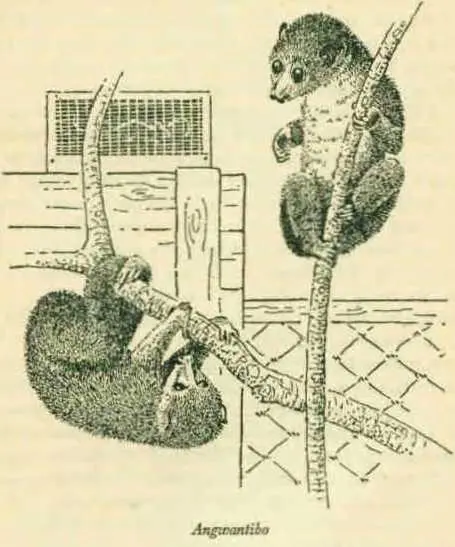

I don’t know what I expected to see: a Pouched rat, or possibly a squirrel, certainly nothing very unusual. But there, blinking up at me out of great golden eyes from the bottom of the basket, was an Angwantibo!

There are certain exquisite moments in life which should be enjoyed to the full, for, unfortunately, they are rare. I certainly made the most of this one, for both Daniel and the hunter thought I had gone mad. I executed a war dance in the middle of the road, I whooped so loudly in my excitement that I sent all the hornbills for miles around honking into the forest. I slapped the hunter on the back, I slapped Daniel on the back, and I would, if I could have managed it, have slapped myself on the back. After all those months of searching and failure I held a real live Angwantibo in my hands, and delight at the thought went to my head like wine.

“Which day you done catch this beef?” I asked, as soon as my excitement had died down somewhat.

“Yesterday, sah, for night-time.”

That meant that the precious creature had been without food and water for twenty-four hours. It was imperative that I got it back to Bakebe immediately and gave it something to eat and drink.

“Daniel, I go ride quickly-quickly to Bakebe to give dis beef some chop. You go follow with dis hunter-man, you hear?”

“Yes, sah.”

I loaded him down with the collecting gear and the beer, and then I hung the basket containing the Angwantibo round my neck and set off along the road to Bakebe. I sped along like a swallow, taking dust, pot-holes, and bridges in my stride and not even noticing them. My one desire was to get the priceless little beast now hanging round my neck into a decent cage, with an adequate supply of fruit and milk. Bakebe was reached at last, and leaving the cycle in the village I panted up the hill towards our hut. Half-way up a dreadful thought occurred to me: maybe my identification had been too rapid, maybe it wasn’t an Angwantibo after all, but merely a young Potto, an animal very similar in appearance. With a sinking heart I opened the basket and peered at the animal again. Quickly I checked identification of various parts of its furry anatomy: shape and number of fingers on its hands, size of ears, lack of tail. No, it really was an Angwantibo. Heaving a sigh of relief I continued on my way.

As I came within sight of the hut I could see John moving along the row of cages, feeding his birds; bursting with pride and excitement I bellowed out the good news to him, waving my hat furiously and breaking into a run:

“John, I’ve got one . . . an Angwantibo . . . alive and kicking. . . . AN ANGWANTIBO, d’you hear?”

At this all the staff, both animal and household, dashed out to meet me and see this beef that I had talked about incessantly for so long, and for which I had offered such a fantastic price. They all grinned and jabbered at my obvious delight and excitement. John, on the other hand, displayed complete lack of interest in the earth-shaking event; he merely glanced over his shoulder and said, “Good show, old boy,” and continued to feed his birds. I could have quite cheerfully kicked him had not my pleasure been so great.

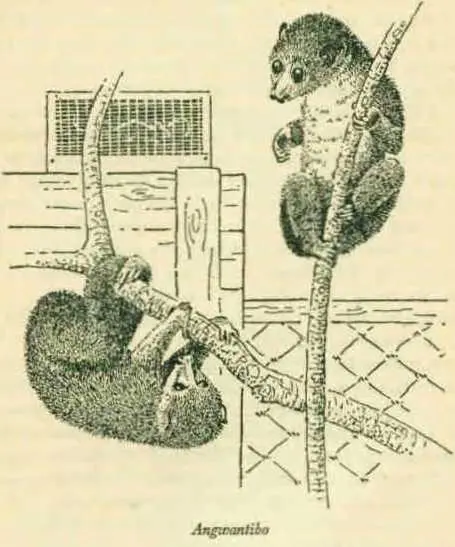

No other animal’s arrival had created half the upheaval that the Angwantibo’s did: a family of Pouched rats that were sleeping peacefully in their cage were routed out unceremoniously, and the cage was swept and cleaned as a temporary abode for the creature. The carpenter was given a big box and told to produce, in record time, the biggest and best cage he could construct, or else suffer a dreadful fate. Various members of the staff were sent scurrying in all directions to procure eggs, pawpaw, banana, and dead birds. At last, when the cage had been furnished with a nice set of branches and there were plates of food and drink on the clean sawdust floor, the great moment came. With a thick crowd around me, hardly daring to breathe in case they disturbed this valuable animal and thus earned my wrath, I carefully tipped the Angwantibo out of the basket and into his temporary home. He stood on the floor for a moment, looking about him; then he walked over to one of the plates, seized a bit of banana in his mouth, and then climbed swiftly up into the branches, and crouching there commenced to eat the fruit greedily. This was a very pleasant surprise; after my experiences with other nervous creatures I had not expected him to eat at once. As I watched him sitting on the branch mumbling his banana I felt quite unreasonably proud, as though I had captured him myself.

“John,” I called in a hoarse whisper, “come and see him.”

“Oh, he’s quite a pretty little animal,” he said.

This was the highest praise you could get out of John for anything without feathers. And indeed he was a pretty little animal. He looked not unlike a teddy-bear, with his thick golden-brown fur, his curved back, and golden eyes. He was about the size of a four-week-old kitten, and though his body was fat and furry enough, his legs, in proportion, seemed long and slender. His hands and feet were extraordinarily like a human’s, except that on his hands the first and second fingers had been reduced to mere stumps. This, of course, gave him a much greater grasping power, for without the first two fingers in the way he could get his little hands round quite a thick branch, and once having got a grip he would cling on as though glued.

After I had stood in silent and awed contemplation of the beast for half an hour, during which time he ate one and a half bananas, he scrambled on to a suitably sloping branch, grasped it firmly with hands and feet, tucked his head between his front legs, his forehead resting on the wood, and went to sleep. Reverently I covered the cage with a cloth so that the sunlight should not disturb him, and tiptoed away.

Every half-hour or so I would creep back to the cage and peep at him to make sure that he had not dropped down dead or been spirited away by some powerful ju-ju , and for the first two days I would leap out of bed in the morning and rush to his cage, even before imbibing my morning cup of tea, a most unheard-of event. John also became infected with my nervousness, and would peer out from under his mosquito-net like a woodpecker from its hole and watch me anxiously as I removed the sacking from the cage front and looked inside.

“Is it all right?” he would inquire. “Has it eaten?”

“Yes, half a banana and the whole of that dead bird.”

Now, there were several reasons for the fuss that was made over the Angwantibo, or, to give it its correct title, Arctocebus calabarensis. The first was that the animal is extremely rare, being found only in the forests of the British and French Carneroons, and even there they do not seem common. The second reason was that they had long been wanted by the London Zoo, and they had asked us specially to try and obtain them a specimen.

Читать дальше