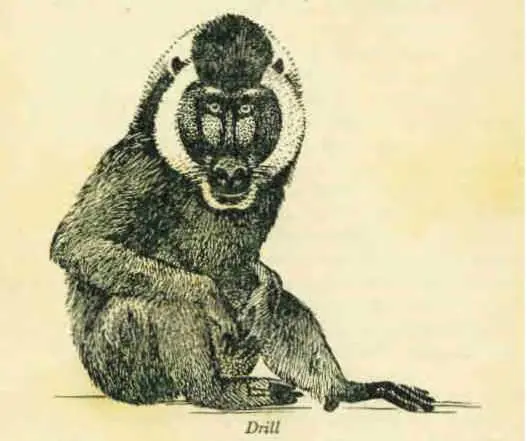

The Drills were the street urchins of the monkey collection. Everything, or almost everything, that you gave to them was first put through the test of whether it was edible or not. If it was not, then it was played with for a while, but they soon lost interest. If a thing was edible (and few things did not come into this category) they would treat it in two different ways. If it was a delicacy, such as a grasshopper, they would cram it into their mouths with all speed in order to prevent anyone else having it. If it was something that was not very attractive they would play with it for a long time, occasionally taking bites out of it, until there was nothing left for them to play with. The Drills, though ugly in comparison to some monkeys, had a brand of charm all their own. Their rolling, dog-like walk; the way they would wrinkle up their noses at you, showing all their baby teeth in a hideous grimace which was supposed to be ingratiating; the way they would walk backwards towards you, displaying their bright pink bottoms as a sign of affection. All these things endeared the Drills to me, but the thing that never failed to melt my heart was the trustful way they would rush to your legs as soon as you appeared, and cling there with hands and feet, uttering hiccuping cries of delight, and peering up into your face with such trustful expressions.

The six Drills I had acquired ruled the roast over all the other and more timid monkeys for a long time. The slender and nervous Guenons could always be persuaded to drop a succulent grasshopper if a Drill charged them, uttering guttural coughs of anger. But one day a new arrival proved their reign at an end: a man walked into the camp, preceded on a length of rope by a three-parts-grown Baboon. Young though he was, he was at least three times as big as the largest Drill, and so, from the moment I purchased him, he assumed control of the monkeys. Apart from his great size he had a shaggy coat of yellowish fur, huge teeth, and a long sweeping, lion-like tail. It was this latter that seemed to give the Drills an inferiority complex: they would examine it for a long time with intense interest, and then turn round and gaze at their own blunt posteriors, ornamented only with a short curled stump of a tail. I called this baboon George, for he resembled a character in the village with this name, and he turned out to be gentle and kind to the other monkeys, without allowing them to take any liberties. Sometimes he would go so far as to allow the Guenons to search for salt on his skin, while he lay prostrate on the ground, a trance-like expression on his face. When he first arrived the Drills banded together and tried to give him a beating up, to prove their superiority, but George was equal to the occasion and gave far more than he got. After this the Drills were very respectful indeed, and would even give a quick look round to see where George was before bullying a Guenon, for George’s idea of settling a quarrel was to rush in and bite both contestants as hard as he could.

George, owing to the fact that he was so tame, was a great favourite with the staff, and spent much of his time in the kitchen. This, however, I had to put a stop to as he was used as an excuse for almost anything that happened: if dinner was late, George had upset the frying-pan; if something was missed there were always at least three witnesses to the fact that George had been seen with it last. So in the end George was tethered among the other monkeys and accepted the leadership without letting it go to his head. In this respect he was most unusual, for almost any monkey, if he sees that all the others respect and are afraid of him, will turn into the most disgusting bully. He also did something that astonished not only his fellow-monkeys but the staff as well. Thinking that he would show the same respect for the chameleons as the other monkeys did, I tied him with a fairly long leash, and his first action was to walk to the full extent of it, reach out a black paw, snatch a chameleon off its branch, and proceed to eat it with every sign of enjoyment. I hastily shortened his leash.

The Red-eared Guenon was the most delightful of the monkeys. About the size of a small cat, she was a delicate green-yellow colour on her body, with yellow patches on her cheeks, a fringe of russet hair hiding her ears, and on her nose a large heart-shaped patch of red hair. Her limbs were slender, and she had great thin bony fingers, like a very old man’s. Every day the monkeys had a handful of grasshoppers each, and the Red-eared Guenon, when she saw me coming, would stand up on her hind legs, uttering shrill bird-like twitterings, and holding out her long arms beseechingly, her thin fingers trembling. She would fill her mouth and both hands with grasshoppers, and when the last insect had been scrunched she would carefully examine the front and back of her hands to make sure she had not missed one, and then would search the ground all round, an intense expression in her light brown eyes. She was the most gentle monkey I had ever come across, and even her cries were this delicate birdlike twittering, and a long drawn-out “wheeeeeeep” when she was trying to attract one’s attention, so different from the belching grunts and loud, unruly screams of the Drills, or the tinny screech of the Putty-noses. George seemed to share my liking for this Guenon, and she seemed to find comfort in being near to his massive body. Peering from behind his shaggy shoulders she would even pluck up the courage to make faces at the Drills.

At midday the sun beat down upon the forest and the camp, and all the birds fell silent in the intense sticky heat. The only sound was the faint, far-away whisper of the cicadas in the cool depths of the forest. The birds drowsed in their cages with their eyes closed, the rats lay on their back sound asleep, their little paws twitching. Under their palm-leaf shelter the monkeys would be stretched out full length on the warm ground, blissfully dreaming, angelic expressions on their little faces. The only one who rarely had an afternoon siesta was the Red-eared Guenon: she would squat by George’s recumbent, heavily breathing form, industriously cleaning his fur, uttering soft little cries of encouragement to herself, as absorbed as an old woman at a spinning-wheel. With her long fingers she would part the hair, peering at the pink skin beneath, in this exciting search. She was not searching for fleas: it cannot be said too often that no monkey searches another for fleas. Should they happen upon a flea, which would be unusual, during the search, it would, of course, be eaten. No, the real reason that monkeys search each other’s fur is to obtain the tiny flakes of salt which appear after the Sweat has evaporated from the skin: these flakes of salt are a great delicacy in the monkey world. The searcher is rewarded by this titbit, while the one who is searched is compensated by the delightful tickly sensation he receives, as his fur is ruffled and parted by the other’s fingers. Sometimes the position would be reversed and the Guenon would lie on the ground with her eyes closed in ecstasy while George searched her soft fur with his big, black, clumsy fingers. Sometimes he would get so absorbed that he would forget he was not dealing with a monkey his own size, and he would handle her a trifle roughly. The only protest she would make would be her soft twittering cry, and then George would realize what he had done and grunt apologetically.

At night the monkeys were untied from their stakes, given a drink of milk with cod-liver oil in it, and then tied up inside a special small hut I had built for them, next door to my tent. The nearer they were to me at night the safer I felt, for I never knew when a local leopard might fancy monkey for his nightly feed, and tied out in the middle of the compound they would not stand a chance. So, each night the monkeys would be carried to their house, dripping milk, and screaming because they did not want to go to bed. George was last, and while the others were being tethered he would make a hasty round of all the pots, hoping against hope that one of the others had left a drop of milk. Then he too, protesting strongly, would be dragged off to bed. One night George revolted. After they had all been put to bed, and I had had my supper, I went down to a dance in the village. George must have watched me going through a crack in his bedroom wall, and he decided that if I could spend an evening out he could also. Very carefully he unpicked his tether and quietly eased his way through the palm-leaf wall. Then he slipped across the compound, and was just gaining the path when the Watchnight saw him.

Читать дальше