I never saw a python that size alive again, and I was never brought another even approaching that size.

The general impression of collecting seems to be that you have only to obtain an animal, stick it in a cage, and the job is done. As a rule it means that the job has only just begun: to locate and capture a specimen may be hard, but it pales into insignificance in comparison with the task of finding it a suitable substitute food, getting it to eat that food, watching to see that it does not develop some disease from close confinement, or sore feet through constant contact with wooden boards. All this in addition to the daily routine of cleaning and feeding, seeing they get neither too much sun nor too little, and so on. There are some creatures who simply will not eat on arrival, and hours have to be spent devising titbits to try and tempt them. Sometimes with this sort of specimen you are lucky, and by experiment you discover something which it likes. But in some cases they will refuse everything, and then the only thing to do is to release the creatures back into the forest. In some cases, which were fortunately rare, you could neither satisfy the animal’s palate, nor could you release it: these cases were the very young specimens. The very worst of these in my experience were the baby duikers.

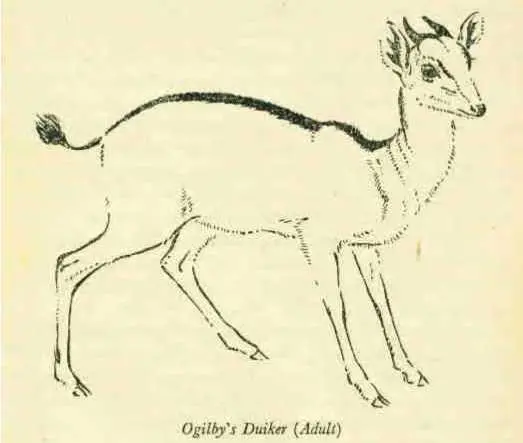

The duikers are a collection of antelope found only in Africa. They range from the size of a fox- terrier to the size of a St Bernard, and in colour from a pale slaty blue to a rich fox-red. It was the latter species of duiker which seemed exceedingly common around Eshobi. During the time I was there it was apparently the breeding season for this duiker, and the hunters out shooting were always finding the young in the forest, or else shooting a female to find that she had been accompanied by her baby. Then the baby was caught and brought to me. Apropos of this I would like to point out that the protection laws for animals in the Cameroons do not take into consideration the breeding season of any animal, so that the hunter is within his rights to kill a

female with young. To him this is a windfall, for he not only gets the mother but the youngster as well, and this without wasting any gunpowder on it. Judging by the number of babies that were brought to me, the annual slaughter during the breeding season must be considerable and, although this species of duiker seems very common at the moment, one wonders how long they will remain so.

When the first duiker was brought to me I purchased it, constructed a suitable cage, and felt very elated at this beautiful addition to the collection. Very soon I realized that these duiker were going to be more difficult than any deer or antelope I had previously dealt with. For the first day the baby would not eat anything, and was very nervous. The next day it realized that I was not going to hurt it and then started to follow me around like a dog, gazing up at me trustfully out of its great, dark, liquid eyes. But it still refused the bottle. I tried every trick I knew to get it to drink: I bought an adult duiker skin and draped it over a chair, and when the baby nosed round it, presented the nipple of the bottle from under the skin. The baby would take a few half-hearted sucks, and then wander off. I tried hot milk, warm milk, cold milk, sweet milk, sour milk, bitter milk, all to no purpose. I put a string around its neck and took it for walks in the adjacent forest, for it was just at the age when it could be weaned, and I hoped that it might come across some leaf or plant that it would eat. We walked round and round, but the only thing it did was to scratch a small hole in the leafy floor and lick up a little earth. Day by day I watched it getting weaker, and I tried desperate measures: it was held down and forced to drink, but this process frightened it so much in its weakened condition that it was doing more harm than good. In desperation I sent the cook off to the nearest town to try and buy a milking goat. Goats are not so easy to come by in the forest areas, and it was three days before he returned. By this time the baby was dead. The cook had brought with him the most ugly and stupid goat it had ever been my misfortune to come into contact with, a beast that proved to be absolutely useless. During the three months we had her she gave, very reluctantly, about two cupfuls of milk. At the sight of a baby duiker she would put her head down and try to charge it. It required three people to hold her while the baby drank. In the end she was consigned to the kitchen, where she provided the main ingredients for a number of fine curries.

Still the baby duikers were brought in, and still they refused to eat, wasted, and died. At one time I had six of these beautiful little creatures wandering forlornly around the compound, occasionally uttering a long-drawn-out, pathetic “barrrrr”, exactly like a lamb. Each time that one arrived on the end of a string I swore that I would not buy it, but when it nuzzled my hand with its wet nose, and turned its great dark eyes on me, I was lost. Perhaps, I would think, this one will be different: perhaps it will drink, and so I would buy it, only to find it was the same as all the others. Six baby duikers wandering around the camp bleating hungrily, and yet refusing everything that was offered, was not the sort of thing to raise anyone’s spirits, and at length I called a halt to the purchase of them. I realized that they would be consigned to the cook-pot of the hunter if I did not buy them, but I felt that this was at least a quick death in comparison to the gradual wasting away. I shall never forget the long and depressing struggle I had with these little antelope: the hours walking in the forest, leading them on strings, trying to tempt them to eat various leaves and grasses, the long wet struggle with the bottle, both the baby and myself dripping milk, but only the smallest amount going down its throat; crawling out of bed at three in the morning to repeat this dampening process, half asleep, the babies struggling and kicking, tearing my pyjamas with their sharp little hooves; the gradually weakening legs, the dull coats, their big eyes sinking into their sockets, and growing dim. It was by this experience more than any other that I learnt that collecting is not as easy as it appears. It was during the time that I was suffering the trials and tribulations of duiker rearing that I engaged what in the Cameroons is known as a Watchnight. It was my first introduction to this fraternity, and throughout my time in the Cameroons I suffered much at their hands. There were two reasons for engaging a nightwatchman: the first was that I needed someone to put the kettle on and heat the water for the night feed of the duikers, and then to wake me up. The second, and more important reason, was that he patrolled the edge of the compound every two hours or so on the look out for driver-ant columns which appeared with such speed and silence. No one, unless they have seen a driver-ant column on the march, can conceive the numbers, the speed, or the ferocity of these insects.

The columns are perhaps two inches wide, and may be two or three miles in length. On the outside walk the soldiers, creatures about half an inch long, with huge heads and great curved jaws. In the middle travel the workers, very much smaller than the soldiers, but still capable of giving a sharp bite. These columns wend their way through the forest, devouring all they come across; if they reach an area which contains a plentiful supply of food they fan out, and within a few minutes the ground is a black, moving carpet of ants. Let one of these columns get into a collection of animals, and within a few minutes your cages would be full of writhing specimens being eaten alive.

Читать дальше