Careful examination disclosed only a few scratches, and after soothing Elias’s hurt feelings we proceeded on our way.

We had been walking some time and carrying on a lively discussion on the difference between rabbits and rats, when I found we were walking on white sand. Looking up, I discovered that we had left the forest, and above us was the night sky, its blackness intensified by the flickering stars. We were actually walking along the banks of the river, but I had not noticed it, for here the brown waters flowed sluggishly between smooth banks, and so there was no babble of water; the river flowed slowly and silently past us like a great snake. Presently we left the sand beach and made our way to the thick fringe of waist-high growth that formed a border between the sand and the beginning of the forest. Here we paused.

“Na for dis kind of place you go catch water-beef; sah,” whispered Elias, while Andraia grunted in agreement. “We go walk softly softly for dis place, and sometime we go find um.”

So we commenced to walk softly, softly through the lush undergrowth, shining our torches ahead. I had just paused to pluck a small tree frog from a leaf and push him into the bottle in my pocket, when Elias hurled his torch at me and dived full length into the leaves. In my efforts to catch his torch as it whirled towards me I dropped my own, which hit a rock and promptly went out. I bungled the catch, dropped the second torch as well, and that followed the first into oblivion. Now we only had the illumination of Andraia’s, which was very anaemic, for the batteries were damp and old. Elias was rolling about in the undergrowth locked in mortal combat with some creature that seemed frightfully strong. I grabbed the light from Andraia, and in the feeble glow I saw Elias rolling about, and held in his arms, kicking and bucking for all it was worth, was a beautiful antelope, its skin patterned with a lovely pattern of white spots and stripes.

“I done hold um, sah,” roared Elias, spitting leaves. “Bring flashlamp, sah, quickly, dis beef get power too much. . . .”

I sprang forward eagerly to help him, tripped heavily over a hidden rock and fell on my face. The last torch flickered and went out. I sat up in the gloom and searched frantically for the torch. I could hear Elias desperately imploring someone to help him. Then, as my groping fingers found a light, a sudden silence fell. I switched on the torch, after several attempts, and shone it on Elias. He was sitting mournfully on his ample bottom getting leaves out of his mouth. “ ’E done run, sah,” he said. “Sorry too much, sah, but dat beef get power pass one man. Look, sah, ’e done give me wound with his foot.” He pointed to his chest, and it was covered with long deep furrows from which the blood was trickling. These had been caused by the sharp, kicking hooves of the little antelope.

“Never mind,” I said, mopping his chest with the iodine, “we go catch dis beef some other time.”

After a search we found the other two torches, and discovered that both bulbs had been broken by the fall. I had forgotten to bring any spare ones and so our only means of illumination was the third torch, which looked as though it was going to give out at any minute. It was plain that all we could do was to call off the hunt and get back to camp while we still had some means of seeing our way. Very depressed we set off, walking as fast as we could by such a poor light.

As we entered the fields on the outskirts of the village Elias stopped and pointed at a dead branch which hung low over the path. I peered at it hopefully, but it was quite bare, with one dead and withered leaf attached to it.

“What ee?” “Dere, for dat dead stick, sah.”

“I no see um. . . .”

Disturbed by our whispering the dead leaf took its head out from under its wing, gave us a startled glance, and then flew wildly off into the night.

“Na bird, sah,” explained Elias.

It was, altogether, a most unsuccessful night, but it was interesting, and showed me what to expect. The fact that the birds slept so close to the ground amazed me, when there were so many huge trees about in which they could roost. But a little thought showed me why they did this: perched on the end of a long slender twig they knew that, should anything try and crawl along after them, its weight would shake the branch or even break it. So, as long as the branch was long, thin, and fairly isolated, it mattered not if it was a hundred feet up, or five feet from the ground. I questioned Elias closely about this, and he informed me that one frequently came across birds perched as low as that, especially in the farm lands. So the next night, armed with large soft cloth bags, we set out to scour the fields. I was armed with a butterfly net with which to do the actual capturing.

We had not gone far when we found a Bulbul seated on a thin branch about five feet above us, an almost indistinguishable ball of grey fluff against the background of leaves. While the other two kept their torches trained on it, I manoeuvred my net into position and made a wild scoop. I don’t suppose the Bulbul had ever had such a fright in its life; at any rate it flew off into the darkness tweeting excitedly. It was then I realized that the upward sweeping motion I had employed was the wrong one. So we went a bit further, and presently came across a Pygmy Kingfisher slumbering peacefully. I scooped the net down on him, he was borne to the ground, and within a couple of seconds was in the depths of a cloth bag. Birds, if placed in a dark bag like this, just lie there limp and relaxed, and do not flutter and hurt themselves during transportation. I was thrilled with this new method of adding to my bird collection, as it seemed far superior to the other methods employed. We spent three hours in the fields that night, and during that time we caught five birds: the Kingfisher, two Forest Robins, a Blue-spotted Dove, and a Bulbul. After this, if I was feeling too tired to wander into the forest at night, we would just walk for an hour or so in the fields a mile or two from the camp, and it was rarely that we returned empty-handed.

Elias felt very deeply the loss of the water-beef, and it was not long afterwards that he suggested we should again hunt by the river, mentioning as additional bait that he knew of some caves in that area. So we set off at about eight o’clock one night, determined to spend all the hours of darkness in pursuit of beef The night did not start well, for a few miles into the forest we came to the dead stump of a great tree. It had died and remained standing, as nearly all these giants did, until it was hollowed out by insects and the weather into a fine shell. Then the weight of the mass of dead branches at the top was too much, and it snapped the trunk off about thirty feet from the ground, leaving the base standing on its buttress roots like a section of a factory chimney, only much more interesting and aesthetically satisfying. Halfway up this stump was a large hole, and as we passed our torches caught the gleam of eyes from its dark interior. We stopped and held a hasty consultation: as before, Andraia and I kept our torches trained on the hole, while Elias went round the other side of the trunk to see if he could climb up.

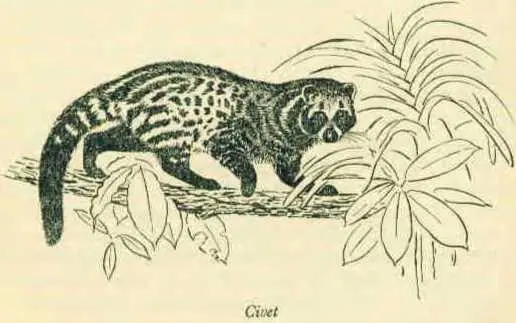

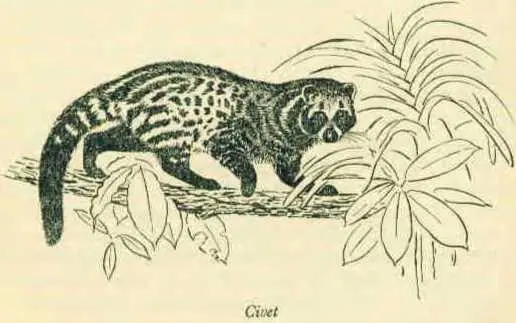

He returned quickly to say that he was too short to reach the only available footholds, and so Andraia would have to do the climbing. Andraia disappeared round the trunk, and shortly after scraping noises and subdued ejaculations of “Eh . . . aehh!” announced that he was on his way up. Elias and I moved a bit closer, keeping our torches steady on the hole. Andraia was two-thirds of the way up when the occupant of the hole showed itself: a large civet. Its black-masked face blinked

down at us, and I caught a glimpse of its grey, black-spotted body. Then it drew back into the hole again

Читать дальше