This often seems to happen on the Iditarod: storms hold off long enough for the leaders to blaze to Nome and then sock the middle of the pack or the tail-enders. Simple probability would suggest the fast-movers get hit on an equal-opportunity basis, but it never seems to work out that way except in a few really notable years, such as in 1991 when Rick Swenson led his team through a screaming blizzard for 50 miles over Topkok to Safety and a dramatic victory over Martin Buser and Susan Butcher.

Soon the snow begins to accumulate more quickly than I’d like. By the time I see the reassuring flash of the Kaltag airport beacon against the clouds 15 miles later, it’s a couple of inches deep and beginning to drift. Socks plows through it unconcernedly and I am doubly glad he’s probably one of the best wind and snow leaders ever to hit the trail. This is the kind of situation in which his marker-to-marker skills are most useful. As my headlamp illuminates each reflective strip he moves methodically toward it, feeling out the trail as he goes. All I have to do is keep finding the markers and Socks will do the rest.

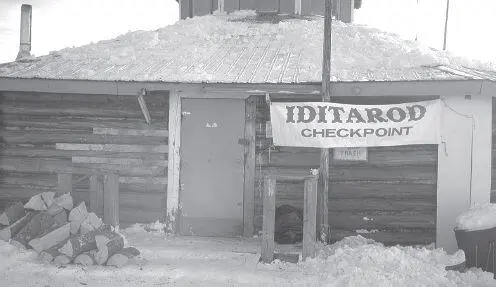

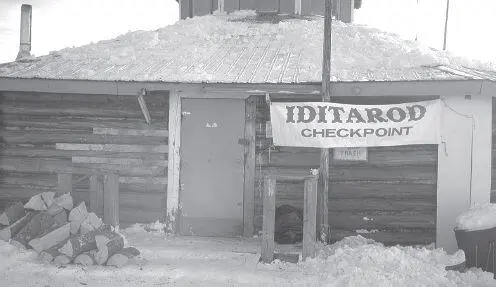

Teams run for several blocks up the main street of Kaltag to the checkpoint. At the end of the 90-mile Kaltag portage, an ancient Native trade route to the Bering Sea coast, Kaltag has been inhabited for many centuries.

We finally leave the Yukon and pull into Kaltag about midnight. People have been living here since the earliest Natives began using the 90-mile portage to the coast. Its 200 or so residents are asleep as we check in. I’ve spent some time here while flying for the race so I’m reasonably familiar with the town.

All things considered, it’s actually been a fairly pleasant and blessedly uneventful run down the legendary river. Because of the snow, I plan to wait until after dawn to start over the Kaltag portage to Unalakleet on the Bering Sea coast. I’m not interested in trying to find an unfamiliar trail in a snowstorm without at least the help of daylight. I’ve already got plenty of problems to deal with and I certainly don’t need to lengthen my odds — after all, it’s still more than 350 notoriously tough miles to Nome.

After taking care of the dogs in a somnambulant daze I stumble up to the checkpoint in the village community center. It is deserted except for half a dozen mushers sprawled out on the benches along the walls. The checker and the vet have retreated to their bunks elsewhere in town after exhorting us to leave as soon as we can.

Lisa and Andy and I aren’t pleased at the implied kick in the pants; we’re fully a day and a half ahead of last year’s rear-enders and will reach Unalakleet two days ahead of the Friday deadline, even with an average run. Indeed, we have every intention of making it to Nome in time for the awards banquet on Sunday afternoon. We need no urging to try to finish the race in a timely manner, and we don’t appreciate being all but tossed out of town just because we’re the last people in the race.

The Kaltag checkpoint has been located for many years in the log-cabin community center.

All of the other mushers save Lisa and Andy and I plan to leave in the wee hours of the morning; they constitute the rest of the now well-defined back-of-the-pack crowd. The three of us plan to stay no more than six to 12 hours behind them all the way to Nome, but for now we (and I in particular) need a few more hours’ rest. We’re making great time and shouldn’t have any trouble reaching Nome for the big party.

In my years as a volunteer pilot for the race, I made a point of working the back of the pack because I figured those were the people who deserved the most help and support. Many days I was the airborne trail sweep checking on the progress of a driver who was a little overdue or who might have been having problems with his or her team. There was never a shortage of volunteers willing to wait and work with the tail-enders. As long as the mushers were still making an effort to get to Nome, we were going to keep the race open until they got there.

They were chasing their dreams; the last thing we wanted to do was to push someone who looked to be lagging but might really just need some solid support and a friendly face to keep the dream from turning into a nightmare. And after last year, I can honestly say I’ve been there, done that.

Training the dogs to rest at every opportunity is an important part of preparing for the Iditarod. Veterans of the trail to Nome waste little time in making themselves comfortable in checkpoints.

March 13–14, 1996—The Iditarod: Kaltag to Unalakleet (90 miles)

By daylight the snow has mostly stopped and the sun is shining much of the time. This is a pleasant surprise, as is the relatively light dusting we’ve received, barely two or three inches. The first item on my agenda is to find the vet so I can drop Diablo. There’s nothing really wrong with him except he’s started to stage occasional sit-down strikes when he doesn’t like something.

This is partly my fault since I borrowed him only a few weeks before the race and didn’t really have a chance to work him into the team or get to know him. In any case, he’s not mine and I’m not going to try to discipline him as I might one of my own dogs. The last thing I want to do is ruin him for Will Barron, who was gracious enough to loan him to me at the last minute.

Dropping Diablo has focused me even more closely on the remaining 11 dogs. We’re almost a week and a half into the race now, and I’m finally learning how much they love to play games with me. Some of them are getting very good at driving me to distraction as the trip stretches on. The veterans especially know how to keep me wondering what’s really happening.

Getting out of a checkpoint is a perfect example. Unlike the Big Name teams which can usually be seen bounding and barking to go even at stops far down the trail, moving my mixed bag of lovable mutts often requires a series of mental fencing matches.

For instance, even though they all know we’re getting ready to go when I move along the line to bootie up, most of them won’t even move when I kneel next to them to work on their feet. Some even resist when I start pulling paws into the cold air — just like humans who don’t want to come out from under the covers when the alarm clock goes off.

After I get the booties on, I hook up the tuglines and stand everyone up. Often as not I must physically move a dog off the straw, like turning over a sleepyhead’s bed and dumping him (or her) onto the floor. Regardless, once I get to the back of the team and hook up the wheel dogs and climb on the runners they all know it’s time to go, and that’s when the real fun begins.

Rocky, a classic Malemute-looking 70-pounder with the most laid-back attitude on the team, is one of the best wheel dogs in the state. However, he’s on his sixth Iditarod and knows every trick in the book. Among other things, he eats his harness whenever I don’t get it off in time at a checkpoint; he’s on his third one, which I’ve already had to tie together in two places with parachute cord.

He’s also figured how to get every last second of rest wherever we stop. Until I give the actual command to go he is an inert mass of fur curled on the straw or the snow. Only when I give the “okay” does he bound to his feet and pull as hard as a bulldozer, all within about half a second. I still get questioning looks from bystanders who wonder if I’m just going to start the team and drag him to the next checkpoint.

Читать дальше