I hope the message translates in the instant-gratification, winner-take-all frenzy pervading the media these days. I’m afraid we back-of-the-packers are hopelessly old-fashioned. Maybe we’d have made good nineteenth-century pioneers, battling our way West with our covered wagons to the promised land beyond the horizon. In any case, I doubt Nike or any of the other big sports advertisers will be beating down our doors to be their spokespersons.

March 8, 1996—The Iditarod: Nikolai to McGrath (48 miles); McGrath to Takotna (23 miles); Takotna to Ophir (38 miles)

The remainder of my stay in Nikolai is blessedly uneventful, divided between feeding dogs and sleeping. My official layover is completed about one a.m.; the dogs are ready to go after their rest and we’re on the trail to McGrath within minutes.

We make good time, at least by our modest standards, but the run to McGrath is downright boring. The endless oxbows in the broad Kuskokwim River blend into one another and I repeatedly nod off on the back of the sled. Again, I’ve flown this area many times but down here on the river I might as well be on another planet as I watch bend after bend slowly unfold in front of me.

As the sun comes up I know we’re at least in the general vicinity of McGrath because I recognize a couple of distinctive hills. However, it’s three more long hours before we finally pull around the last tree line to see the town sprawled out along the high river bank.

As soon as we’re into the checkpoint and the dogs are taken care of, I drop Bea. She hasn’t been pulling since the beginning of the race and I have finally given up hope she will toughen up on the trail. I evidently made a mistake bringing her; she had foot problems all winter and ran far fewer miles than the other dogs. With 20–20 hindsight, I wish I’d brought one of my other seasoned veterans, but there’s not much I can do now.

A team leaves McGrath, whose main street is the airport parking ramp. The town is a major staging point for the Iditarod logistics effort. Everything for the remote checkpoints at Rohn, Ophir, Cripple, and Iditarod is flown from here by the Iditarod Air Force. Many mushers take their 24-hour layovers at McGrath because of its good facilities.

I spend only a few hours in McGrath, just long enough to feed the dogs and make a quick trip to the local hardware store for more hose clamps to finish fixing the sled. In previous years when I was flying for the race McGrath was one of our major bases and I know the town well.

Founded in 1907 as a steamboat landing to serve the Ophir gold district, it assumed its current identity when the Army built an air base here just before World War II. Even today main street for the town’s 500 people is the airport parking ramp. Among other things McGrath has the only bar for 200 miles in any direction — McGuire’s, right next to the airplanes along with two grocery stores, hardware store, roadhouse/restaurant, airline terminal, flight service station, and local public radio station, KSKO-AM. The radio station is the only one for about the same radius as the bar and is a favorite information source for mushers on the trail.

As much as I’d like to grab a quick brew at McGuire’s ($3.00 per can and you have to put up with the bartender’s atrocious jokes), I have to get moving. I hope to be in Ophir tonight, almost 60 miles up the trail. We roll out of the checkpoint and across the Kuskokwim and are on the 20-mile trail to Takotna a little past noon. I’m running during the heat of the day again, but I don’t have much choice.

I soon discover this relatively short haul involves a nonstop climb up a long ridge before it drops abruptly down to Takotna. It takes forever for the dogs to pull up the endless slope over a million moguls created by fast-moving snowmachines. There is nothing more frustrating for a dog team than an uphill trail with two- and three-foot moguls. The dogs can’t get up enough speed to pull cleanly over the tops of the bumps, resulting in a nauseating pull-drop-slam-stop rhythm which causes the team to work twice as hard as on a smooth trail.

Even the expansive view as we creep along the top of the ridge can’t make up for the drudgery. The dogs are much relieved when we finally roar down the 500-foot hill to the river for the last couple of miles up to the town. By the time we pull to a stop in front of the tiny town’s combination community center and school it’s taken us almost four hours; most other teams have done it in three or less. I’m going to have to get used to spending a lot more time on the runners than everyone else, but as long as the dogs keep moving, so will I.

My plan is to change my runner plastic here, snack the dogs, and move on to Ophir. Changing the plastic normally takes 10 minutes, but as I rip off the scarred bottoms that have withstood everything since Fourth Avenue I find a hidden legacy of the Post River collision: the heads have popped off four of the retaining screws on the metal guides which hold the plastic. I can’t get the new plastic back on without re-anchoring the metal to the wooden runner.

This is well beyond the capability of my minimal trail tool kit. Fortunately the checker finds a power drill and we string an extension cord from the community center to the sled, across the village’s main street. I carefully countersink new holes and reattach the metal with drywall screws which have magically materialized from someone’s garage. It takes two hours to do everything properly. I’m glad I didn’t wait to change the plastic at Ophir, a true ghost town where I’d be strictly out of luck.

I’m finally ready to move out just after sunset on the 38-mile run to Ophir, which the checker assures me is actually closer to 30. Just before I pull the hook, Rich Bosela, who finished the race a few years ago, comes back into town with apparently ill dogs.

They could have eaten spoiled meat; the recent warm weather has partly thawed some of the meat in the food bags and I’ve heard several reports of sick dogs. I’ve carefully avoided feeding my team anything that even appears to have melted and so far haven’t had any problems. I hope Rich can get everything squared away and get moving again; he’s a charter member of the back-of-the-pack group and has been good company.

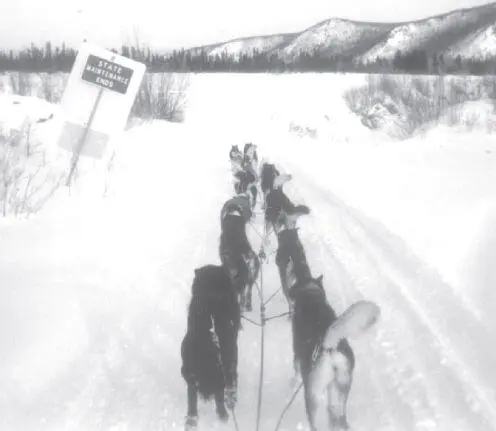

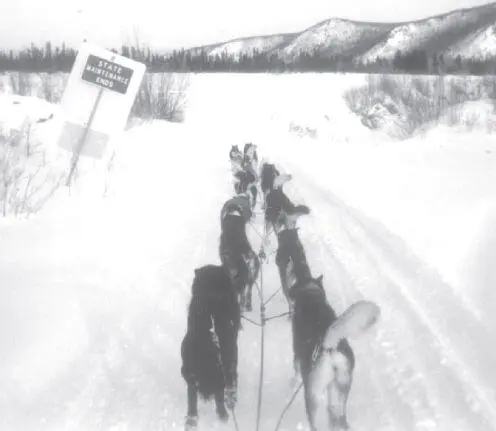

The one-lane gravel road from Takotna to Ophir was built in the 1920s to connect the mines in the rich Innoko mining district to a steamboat landing on the Kuskokwim River. Although isolated from the state’s highway network, it is still maintained for vehicles during the summer — at least as far as this “State Maintenance Ends” sign, a mile or so short of the Ophir

The trail to Ophir follows an old road built back in the 1920s to connect the mining district to a steamboat landing on the Kuskokwim River. Barges have replaced the steamboats and several of the mines are still active, so the state maintains the road. It’s not connected to the rest of the state road system and isn’t plowed over to Ophir in the winter, but it’s just fine for dog teams and snowmachines.

The first thing we encounter on leaving Takotna is a brutal eight-mile grade up to the pass leading to the Innoko River and Ophir. The climb is all on the road but that doesn’t make the 1,000-foot ascent any less difficult. The dogs pull steadily up the slope as light snow starts to fall. I’m thankful my team includes more big dogs than most; they may be slow, but they provide solid pulling power for hills like this.

Читать дальше