On Andromeda's gun-deck, Lieutenant Frey received the message to cease fire from Mr Paine who also added the request for the larboard guns to be withdrawn and the ports shut.

'What's amiss?' asked Frey, unable to do more than shout to hear his own voice.

'We need your men on deck, sir. Most of our fellows are aboard the Frenchman and that bloody Russian's just coming up on her disengaged side!'

'Where's the captain?' Frey asked.

'I last saw him going over the side with his hanger in his teeth.'

'Good God!'

Frey turned and began bellowing at his men.

As McCann shuffled forward in the oppressive gloom of L'Aigle's gun-deck, resistance became increasingly fierce. It was clear that some of the soldiers had either retreated to the shelter of the guns amidships, or had been held in reserve there. A volley met the marines and several men fell. McCann took shelter behind the round bulk of the main capstan and prepared to return fire as if in his native woods, sheltering behind the bole of a hickory tree.

As his eyes became accustomed to the semi-darkness McCann began to select targets and fire with more precision. A small group of marines took cover either with him or behind adjacent guns. He was conscious of an exchange of fire at the far end of the deck where Ashton was attacking down through a pale shaft of sunlight lancing in by way of the forward companionway. It was clear that there, too, resistance was disciplined and effective. Then above the shots and yells, McCann heard Ashton's voice.

'McCann! Where the devil are you? Come and support me you damned Yankee blackguard!'

Ashton's intemperate and ill-considered plea took no account of McCann's own predicament, but was a reaction to the situation Ashton's headstrong action had landed him in. But its insulting unreasonableness struck a chord in McCann's psyche, and his spirit, loosened by the heat of battle, broke in hatred, remorse and the final bitter explosion of his reason.

And then McCann saw Ashton standing half way down the forward companionway, illuminated by the shaft of light that lanced down from the clear blue sky above. He presented even an indifferent marksman a perfect target, and the fact that no Frenchman amidships had yet hit him confirmed McCann in his belief that Ashton had been providentially delivered to his own prowess. He knew the moment was fleeting and his Tower musket was discharged: McCann drew a pistol from his belt, laid it on Ashton's silhouetted head, and fired. As the smoke from the frizzen and muzzle cleared Ashton had vanished. McCann's triumph was short-lived; a second later he heard Ashton's voice: 'McCann, give fire, damn you!'

Alone, his bayonet fixed and his musket horizontal, Sergeant McCann forsook the shelter of the capstan and, with a crash of boots and an Indian yell, ran forward. Four balls hit him before he had advanced five paces, but his momentum carried him along the deck and he could see, kneeling and levelling a carbine at him, a big man whose bulk seemed to fill the low space.

'Sergeant McCann...!' Ashton's plaintive cry was lost in the noise of further musketry. McCann saw the yellow flash of the big horse-grenadier's carbine. The blow of the ball stopped him in his tracks, but it had missed his heart and such was his speed that it failed to knock him over. He shuffled forward again and in his last, despairing act as he fell to his knees, he thrust with his bayonet. Gaston Duroc of the Imperial Horse Grenadiers parried the feeble lunge of the British marine with his bare hand.

'Sergeant McCann, damn you to hell!' cried Lieutenant Ashton, retreating back up the forward companionway and calling his men to prevent the counter-attacking French from following and regaining the upper-deck.

Captain Drinkwater was aware of men about him, though there were few enough of them.

'My lads...' he began, but he was quite out of breath and, besides, could think of nothing to say. It would be only a moment or two before the Russians stormed into L'Aigle and wrested the French ship back from his exhausted men. He closed his eyes to stop the world swaying about him.

'Are you all right sir?'

He had no idea who was asking. 'Perfectly fine,' he answered, thanking the unknown man for his concern. And it was true; he felt quite well now, the pain had gone completely and someone seemed to be taking his sword from his hand. Well, if it meant surrender, at least it did not mean dishonour. If they survived, Marlowe and Birkbeck would manage matters, and Frey ...

The bed was wondrously comfortable; he could sleep and sleep and sleep...

He could hear Charlotte Amelia in the next room. She was playing the harpsichord; something by Mozart, he thought, though he was never certain where music was concerned. And there was Elizabeth's voice. It was not Mozart any more, but a song of which Elizabeth was inordinately fond. He wished he could remember its name ...

'Congratulations, Lieutenant.'

Frey bowed. 'Thank you, sir, but here is our first lieutenant, Mr Marlowe.' Frey gestured as an officer almost as dishevelled and grubby as himself came up. A broken hanger dangled by its martingale from his right wrist. In his hands he bore the lowered colours of L'Aigle.

'What's all this?' Marlowe demanded, his face drawn and a wild look in his eye. His cheek was gouged by a black, scabbing clot. The appearance of the Russian had surprised him too, for he had been occupied with the business of securing the French frigate upon whose deck the three men now met.

'Captain Count Rakov, Marlowe,' Frey muttered and, lowering his voice, added 'executing a smart volte-face in the circumstances, I think.'

'I don't understand ...'

'For God's sake bow and pretend you do.' Frey bowed again and repeated the introduction. 'Captain Count Rakov ... Lieutenant Marlowe.'

'Where is Captain Drinkwater?' asked the Russian in a thick, faltering accent. 'I see him on the quarterdeck and then he go. You,' Rakov looked at Marlowe, 'strike ensign.'

'I, er, I don't know where Captain Drinkwater is ...' Marlowe looked at Frey.

'He is dead?' Rakov asked.

'Frey?'

'Captain Drinkwater has been wounded, sir,' Frey advised.

'And die?'

'I do not believe the wound to be mortal, sir.' Frey was by no means certain of this, but the Russian's predatory interest and the circumstances of his intervention made Frey cautious. Rakov's motives were as murky as ditchwater and they were a long way from home in a half-wrecked ship. Frey was not about to surrender the initiative to a man who had apparently changed sides and might yet reverse the procedure if he thought Captain Drinkwater's wound was serious.

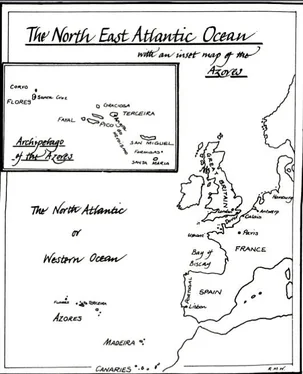

'In fact, Mr Marlowe,' Frey lied boldly, 'he left orders to proceed to Angra without delay.' Frey turned to Rakov and decided to bluff the Russian and hoist him with his own petard. And he asked that you, Count Rakov, would assist us to bring our joint prizes to an anchorage there. He regretted the misunderstanding that occasioned us to fire into each other. I believe there was some confusion about which ensigns these ships were flying.'

Rakov regarded Frey with a calculating and shrewd eye, then turned to Marlowe. 'You command, yes?' he broke the sentence off expectantly.

'Yes, yes, of course,' Marlowe temporized. 'If that is what Captain Drinkwater said ...'

'He was quite specific about the matter, gentlemen,' said Frey with a growing confidence.

'You British ...' said the Russian and turned on his heel, leaving the non sequitur hanging in the air.

'Whew,' exhaled Frey when Rakov was out of earshot.

'D'you mind telling me what all that was about, damn it?' Marlowe asked.

'I think we won the action, Frederic, in every sense. Now, you had better see whether we have enough men to get this bloody ship to Terceira.'

Читать дальше