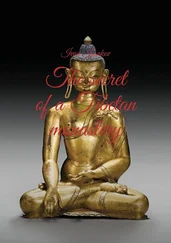

Pandion, however, considered that the sculptors of Kidogo’s tribe lacked a profound understanding of form. The same was true of the masters of Aigyptos. The statues of Tha-Quem were lifeless in their fixed poses despite the precision with which they were carved and the brilliant finish that resulted from many centuries of experience. Kidogo’s people, on the contrary, recorded in their carvings the most acute impressions but only in partial, deliberately stressed details. When the young Hellene pondered over the work of the local craftsmen, he had a vague feeling that the path to perfection in sculpture must lie in some completely new direction and not in the blind effort to reproduce nature nor in attempts to reflect certain partial impressions.

Kidogo’s people loved music and played on complicated instruments made of rows of little wooden planks fixed on long hollow gourds. Some of the sad and tenderly expansive songs affected Pandion greatly, reminding him of the songs of his homeland.

Cavius was sitting beside the dying fire near their house, chewing stimulating leaves* and pensively stirring with a stick ashes in which yellow fruits were baking.

( Leaves from any bush of the Sterculiaceae family.) He had learned to make flour from bananas and bake cakes from it.

Pandion came out of the house, sat down beside his friend and looked idly over the high rows of the houses and at passers-by.

A soft evening light descended on the dusty paths and was lost in the motionless branches of the shady trees.

Suddenly Pandion’s attention was attracted to a passing woman. He had noticed her when they first arrived at Kidogo’s village, but since then had not chanced to meet her. He knew that it was Nyora, the wife of one of Kidogo’s relatives. Even in a tribe whose women were famous for their beauty, Nyora was outstanding. She walked slowly past the friends with all the dignity of a woman who was conscious of her own beauty. Pandion gazed at her in frank admiration, and the creative urge came back to him in all its former strength.

Nyora wore a piece of greenish-blue cloth tightly bound round her loins; a string of blue beads, heavy heart-shaped earrings and a narrow gold band on her left wrist were her only ornaments. Her short black hair was gathered on the crown of her head and braided in a fantastic style that made her head seem longer. Her big eyes showed calm from under long lashes and the cheek-bones under the eyes formed little round hillocks, like those of healthy and well-fed children amongst the Hellenes.

Her smooth black skin was so resilient that her body seemed to be cast from iron; it shone in the rays of the setting sun, its coppery hue turning to gold. Her long neck, inclined slightly forward, gave her head a proud poise.

Pandion admired Nyora’s tall and lithe figure, her easy but restrained movements. To him she seemed like an incarnation of one of the three Graces, goddesses that, according to the belief of his country, had control over living beauty and made its attraction irresistible.

Suddenly the Etruscan gave Pandion a light tap on the head with his stick.

“Why don’t you run after her?” asked Cavius, half in joke and half in chagrin. “You Hellenes are always ready to fall in love with a woman…”

Pandion looked at his friend without anger but rather as though he were seeing him for the first time and then threw his arms impetuously round his shoulders.

“Listen, Cavius, you don’t like to talk about yourself… Aren’t you at all interested in women? Don’t you feel how beautiful they are? Don’t you feel that they are part of all this,” Pandion made a sweeping circle with him arm, “the sea, the sun, the beautiful world?”

“No, whenever I see anything beautiful I want to eat it,” laughed the Etruscan. “I’m only joking,” he added in serious tones. “You must remember that I’m twice as old as you and behind the bright face of the world I can see the other side that is dark and ugly. You have already forgotten Tha-Quem.” Cavius passed his finger over the red brand on Pandion’s back. “I never forget anything. I’m jealous of you, you will create beautiful things, but I can only wreak destruction in the struggle against the forces of darkness.” Cavius was silent for a few moments and then continued in a trembling voice: “You don’t often think of your own people back at home… It is many years since I saw my children; I don’t even know whether they are alive, whether my clan still exists. Who knows what may have happened there, in the midst of hostile tribes…”

The sorrow that tinged the voice of the always reticent Etruscan filled Pandion with sympathy. But how could he comfort his friend? And then the Etruscan’s words struck home painfully: “You don’t often think of your own people back home…” If Cavius could say such things to him… Could it be true that Thessa, his grandfather, Agenor, all meant so little to him? If such were not the case, he would have become as morose as Cavius, he would not have absorbed the great variety of life, and how would he have learnt to understand beauty? Pandion’s thoughts were so full of contradiction that he could not understand himself. He jumped up and suggested to the Etruscan that they go to bathe. The latter agreed, and the two friends set out across the hills beyond which, at a distance of five thousand cubits from the village, lay the ocean.

A few days before this Kidogo had gathered together the young men and youths of the tribe. The Negro told his people that his friends had no property of any kind except their spears and loin-cloths and that the Sons of the Wind would not take them aboard their ships without payment.

“If every one of you helps them just a little,” said Kidogo, “the strangers will be able to return home. They helped me escape from captivity and return to you.”

Encouraged by the general approval that followed, Kidogo suggested that they all go with him to the plateau where the gold deposits were and that those who could not go should contribute ivory, nuts, hides or a log of valuable wood.

Next day Kidogo informed his friends that he was going away on a hunt, but refused to take them with him, recommending that they save their strength for the forthcoming journey.

Kidogo’s travelling companions, therefore, knew nothing of the real object of his expedition. Although the problem of payment for the journey home worried them, they hoped that the mysterious Sons of the Wind would hire them as rowers. If the worst came to the worst, Pandion knew he would be able to offer the stones that came from the south, the old chief’s gift to him. Cavius, also without a word to Kidogo, gathered the Libyans together two days after his Negro friend had left and set out up the river in search of blackwood trees; he wanted to fell a few of them and float them downstream on rafts of light wood as the ebony and other blackwoods were too heavy to float in water.

Pandion was still lame, and Cavius left him in the village despite his protests. This was the second time that his comrades had left Pandion alone, the first time had been when they went on the giraffe hunt. Pandion was infuriated, but Cavius, superciliously thrusting out his beard, said that on the first occasion he had not wasted time and could do the same again. The young Hellene was in such a rage that he could not speak, and he rushed away from his friend, feeling deeply insulted. Cavius ran after him, slapped him on the back and asked his forgiveness, but, nevertheless, insisted on Pandion remaining behind, to complete his recovery.

After a long argument Pandion agreed; he regarded himself as a pitiful cripple and hurriedly hid himself in the house so as not to be present when his healthy comrades were leaving.

Left alone Pandion felt a still stronger urge to test his ability — he thought of his success with the statue of the elephant trainer. He had seen so much death and destruction during the past few years that he did not want to have anything to do with such an unenduring medium as clay; he wanted to work with more durable material. No such material was at hand and even if he found it, he still had no tools with which to carve.

Читать дальше