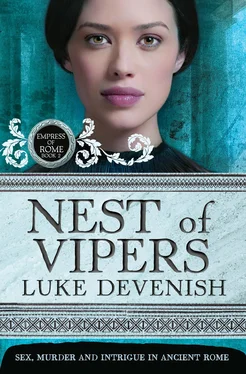

Luke Devenish - Nest of vipers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Luke Devenish - Nest of vipers» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторические приключения, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nest of vipers

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nest of vipers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nest of vipers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nest of vipers — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nest of vipers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The slave struck the prostrate choirmaster twice on the legs, and the hapless man bit back his pain as the forty assembled children of the Patrician Youth Choir bit back their own cries of fear and distress.

The room stayed in tomblike silence. Tiberius rose unsteadily from his chair and fell to his knees before the tapestry.

'Civil war can be avoided, Caesar,' Sejanus said from the other side of the door, still watching Tiberius through the peephole.

The reminder that Sejanus was still there snapped Tiberius from the tapestry. 'How?'

'By removing the ringleaders.'

'Who are they?'

'I have made a list,' said Sejanus. He began to slip a sheet of papyrus under the door. 'And I have detailed some other matters — '

'More tall tales from spies, you mean.' Tiberius watched the papyrus curl under the door — as did the frightened children of the Patrician Youth Choir. But he didn't move to read it. 'I will not have my daughter-in-law attacked, Sejanus,' he said, as his eye returned to the tapestry. 'Grief has made Agrippina unstable — she isn't well. She no longer knows her own mind.'

Another wave of hurt crushed Sejanus. 'But she plots against you, Caesar. I have the evidence. She is a danger to you.'

'She no longer knows her own mind.'

Sejanus said nothing for a time. Then he said quietly, 'She is innocent — a figurehead for the sedition of others.'

Tiberius ran his hands along the rich embroidered fabric. 'She is a widow worthy of Rome's respect.'

'You will see that I have not even listed her,' said Sejanus. 'You have no reason to fear for her, Caesar.'

'Good. Very good…'

Another child began to weep from the choir. The slave with the iron rod tensed himself, expecting to be called for further disciplinary measures. But Tiberius only brushed aside the tapestry from the wall.

'Why don't you sing something?' he said over his shoulder.

The children gaped at each other in bewilderment. From the floor in front of the curule chair the prostrate choirmaster dared to raise his head a fraction. 'What would please you, Caesar?'

Tiberius gazed into the alcove. 'Something pretty…'

The choirmaster looked to the rod-wielding slave to see if he would be beaten again, but the slave seemed as confused as he was. The choirmaster stood gingerly, his legs black with bruises. 'Choir,' he called to the frightened children, 'let's start with number fourteen.'

The children haltingly began to sing as a tiny voice inside Tiberius willed him not to move a muscle of his hand, even though he let it hover in the air. The tiny voice then willed him not to go any further, even though his hand began to circle and descend. The tiny voice then told him he was weak and effeminate if he intended giving in to his cravings, and that if he went any further it was clear he lacked the resolve of the Fathers.

The tiny voice was familiar — a voice Tiberius knew and loved — yet he hadn't heard it in many long years. It was the voice of his dead brother.

'Shut up! Just shut up!' Tiberius screamed as his fingers made contact with the rim of the large silver bowl.

The children snapped into silence.

'Who told you to stop?' Tiberius turned on them. 'Sing!'

The children lurched into song again as Tiberius felt the contents of the bowl with his fingertips.

From the peephole at the door Sejanus saw everything. He was shamed by the sight — disgusted by it too. He knew that his Emperor was debasing himself. But he also knew that it was best that it happened — best for Tiberius, best for Rome. 'Shall I summon the slave to remove your night soil, Caesar?' he spoke through the door join.

Tiberius shook his head. Then he placed his face inside the bowl. The taste was unexpectedly sweet; the draught of the Eastern flower had obliterated all the filth and impurities with its healing magic.

'Have you read the names upon the ringleader's list yet, Caesar?'

The Emperor paused in lapping his excrement. 'I will read it shortly,' he replied, feeling much better humoured. 'I shall read it with considerable attention.'

Drusus's eyes were on Sosia's yellow stola. The feather-light fabric of it transfixed him in the last of the sun's rays, which streamed through the windows of the dining room. The desire to reach out from where he lay on his couch and touch the lovely garment was so strong it was dangerous. It made Drusus's heart beat like a musician's instrument; it made the sweat gather in the pits of his arms. His practised look of calm hid the frenzy of excuse-making that raged inside his mind. If he touched it, Drusus told himself, he could claim he'd seen a bee on Sosia's arm and that he'd sought to brush it off. Or he could say he'd seen the stola about to snag on a furniture nail. Or he could even say that he simply wanted to feel it, which was the truth — why should it be thought of as shameful? The garment was overwhelmingly beautiful. It was a pleasure to Drusus's eyes — and it was surely an unparalleled pleasure to the skin, too. His hand left the dining cushion and floated in the air, towards his mother's unwitting friend as she delivered her news.

'Drusus,' said his grandmother Antonia.

His hand fell back to the dining cushion with a clap as Antonia looked sternly at him. 'Have you been listening?'

Drusus reddened. His grandmother knew everything — all the contemptible urges and needs that dwelled within him. She knew what he wanted; she knew what he was. She had even written a letter about it to his father, Germanicus, that he had been ordered to deliver in person so that he would receive the consequences. But when the family came to Antioch, they found his father dead. His grief-maddened mother had opened the letter, but the words inside had not been written by his grandmother at all; they said nothing about him. When Drusus read the letter himself, it made no sense; it just contained lurid accusations. All that had mattered to Drusus was that the terrible words — 'transvestite', 'perversion', 'obscene' — had not been there and would never be seen. But his grandmother still knew, even though she had not sought to use it against him since.

'Listening to what?' said Drusus.

There was an uncomfortable pause among the dinner guests. Sosia and her senator husband, Silius, were Agrippina's guests of honour, both seated at her right. Antonia and her widowed daughter Livilla were also in attendance, along with all of Agrippina's children except for Nero. The two youngest sisters began to giggle in their chairs, but the older girl, Nilla, watched her brother Drusus with quiet interest. Agrippina cast an indulgent look at Sosia and Silius, but Antonia's look grew darker.

'Listening to what Sosia has been telling us,' Antonia said. 'It is very serious, Drusus — the Emperor has worked himself up into a state about it.'

'I think it's ridiculous,' said Agrippina. 'What on earth does it matter?'

Antonia's look moved to her daughter-in-law. 'Tiberius is not.. wholly well.'

I hovered among the serving slaves, taking all this in.

'His mind is troubled,' Antonia said — and it was all she would say.

'He's madder than ever,' said Sosia, who had none of Antonia's tact.

The corpulent Senator Silius looked pained from where he sprawled on his dining couch.

'Well, it's true,' said Sosia for his benefit. 'We're among friends here and we can speak with honesty, can't we? His mind is slipping, cracking, whatever you wish to call it. He's making decisions that are deranged — he finds treasonous activities that simply aren't there.'

'He was kind when he was young — a good and decent man,' said Antonia. 'I'll never forget how good he was to me when his brother, my husband, died — your great father, Livilla.'

Curled up like a cat on her own couch, Livilla said nothing, concentrating intently on her food.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nest of vipers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nest of vipers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nest of vipers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.