Michael Chabon - Gentlemen of the Road

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Michael Chabon - Gentlemen of the Road» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторические приключения, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gentlemen of the Road

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gentlemen of the Road: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gentlemen of the Road»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gentlemen of the Road — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gentlemen of the Road», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The elephant withdrew its burled trunk from Filaq's embrace and turned its slow head on the scraping millstones of its vertebrae, left, right, as if indicating the men around it, producing a clucking sound with its lips or throat. It made a backward lurch toward the troopers. One of the horses shied, and its rider raised his lance and drove it deep into the flank of the elephant.

Life blew in gusts from the hole in the side of the elephant with a rank smell and a comic flatulence. It sounded a few flat whuffling notes that seemed to raise a stirring echo from far away, and then it pitched forward, its massive skull dragging it down. The architecture of the head struck the ground with a formidable tolling, but the rest of it hit with the light snap of brushwood. Its fall kicked up a roil of dust and delicate falling flakes of scurf

“Damn me,” Amram said, unslinging Defiler of All Mothers from his back. The impostors threw down the streaming banners to be trampled in the mud, unfurled the candelabrum flag of Khazaria and drew their swords. Amram reared up and began to uncoil the bite of his Viking ax, but before he had the chance to swing it, one of the impostors dragged Filaq off the body of the dead beast and, reaching for the collar of the stripling's tunic, ripped the front away, revealing a white belly with a soft prominence, a curve of hip and two yards of linen swaddling cloth wrapped tightly around a slender chest. Filaq struggled, growled, cursed and finally screamed as the soldier tore off the linen drawers, revealing a gonfalon of russet hair with nothing to inspire it but the breeze. With a flourish of his dagger-one of those bold gestures so dear to emancipators-the soldier slit the swaddling cloth, and it sprang from Filaq's body, baring the startled gaze of a pair of breasts shaped by the hand of nature to fit the cup of a lover's palm.

On that plain of mud and grass and staring faces, along the battlements and bartizans of the walls of Atil barbed with pikemen and archers, from the Black Sea to the Sea of Khazar, from the Urals to the Caucasus, there was no sound but the wind in the grass, the clop of a sidestepping horse, the broken breathing of the Little Elephant, Filaq, with whom they had marched and slept and shivered, the son, the prince they had raised up on their shoulders to rule them as their bek, the revenger of the rape of their sisters and the burning of their houses and the pillage of their goods. All Zelik-man's disdain, all his resentment toward the foul-mouthed spoiled stripling who had plagued him since the rescue at the caravansary vanished with the double shock of the elephant's slaughter and the revelation. In their place he felt only pity for a white thing flecked with mud, a motherless girl, drooping in the grip of the soldier like a captured flag.

Before Amram could recover, the mounted impostors had him at the point of their lances. He studied the angles and distances, the lean faces under the helmets, the wonder of the girl, the glinting steel tips of the lances. He threw down his ax. They bound his arms behind him, and with the girl they drove him toward the gates of the city Zelikman reached for Lancet, but as if he had heard the snick of the blade Amram whipped his head around, seeking among the baffled faces of the Brotherhood for his old friend's, and in his own impassive mien there was neither a warning against hasty action nor the fatalism of defeat but a hint of amusement more useful and wise: Can you top this? And Zelikman recollected his own intelligence, forgot his outrage, resisted the urge to act in panic and left his blade where, for now, it belonged.

Like apes on a rock at sunset, like crows in the trees, like the bells in the watchtowers of a city under attack, the men of the Brotherhood fell to talking all at once, as those nearest the gates and those at the extremes of the encampment sought to reconcile the stark prodigies of observation with the grandiose inventions of rumor.

“Master?” Hanukkah said, approaching Zelikman warily, one hand extended like a man searching out a stairhead in the dark. He wore a mail shirt and one boot and no pants, with his arm in a sling and a bruise on his cheek, a hangover folded about him like a cloak, tottering, squinting, a loop of his woolen bedroll caught in a link of his mail so that the blanket dragged along behind him in the mud. “Is that you?”

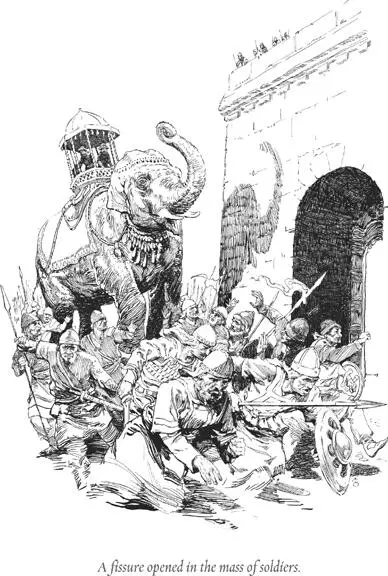

And he reached out, his pudgy cheeks slack, his bright little eyes drained by surprise of any visible emotion, to tug at one of the braids of Zelikman's beard. But the day was not yet replete with wonders, because before Zelikman could reply there were shouts from the rear and then the blatting tantara of an inhuman horn. A fissure opened in the mass of soldiers, and like a dike giving way before the ransacking arm of a flood they fell back or ran to get out of the path of Cune-gunde, the elephant, who came shambling toward the gates of Atil, her hide scrubbed, oiled and glistening in the sun, caparisoned in purple silk and cloth of gold, the tips of her tusks capped with gilded leather sheaths. On her back in a large rush basket jostled the nephew of Joseph Hirkanos with three or four of his uncles, clutching the sides of the basket. The effect of the fine silk robes they wore, like that of the bright ribbon braiding their beards and moustaches, was spoiled to a degree by the expressions of terror on their faces as she ran wild.

Cunegunde stopped beside the body of the dead elephant, and stared at it with an unreadable expression. She snuffled, and rumbled, and investigated its sounds and the pocks and scars of its hide. She redistributed her weight impatiently among the pillars of her frame, and some fundamental injustice or harsh fact about the world seemed to confront her afresh, with no gain in meaning or message. The dead animal was a distant cousin to her at best, Zelikman supposed, no nearer kin than Amram was to him.

Zelikman clapped Hanukkah on the shoulder and then ran toward the elephant. The Radanites riding in the howdah, not yet fully recovered from their jaunt, appeared taken aback by the sudden appearance, amid the legs of their merchandise, of one of their own guild. Even Joseph cried out in alarm as Zelikman grabbed hold of one of the gilt-embroidered purple strips that fluttered from the withers of the elephant and used it as a rope to pull himself up to the shoulders of the beast, whom his disguise neither alarmed nor, apparently, deceived. Twenty years earlier, at the St. John's Fair at Mainz, a Jewish boy sneaked into the stall where the elephant was kept for the night and fed her a ripe pear, and patted her flank, and spoke a kind word in the holy tongue, which he believed at the time to have been the original language of elephants and men, and now when that boy, grown to a man, lost his footing on the elephant's flank and began to slide down the silken panel to the ground, Cunegunde reached back and, with the tip of her trunk against the seat of his breeches, held him steady until he could regain his purchase.

“The offer to join us was a simple one, really,” Joseph Hirkanos said when Zelikman tumbled into the basket, looking him up and down from the tips of his curled slippers to his blackened hedgehog of a plaited beard to the clumsy windings of his head wrap. “But I divine that you find a way to complicate everything.”

CHAPTER ELEVEN

At the Feast of Booths it was the custom of the beks of Khazaria to pitch their leaf tents in the yard of the prison fortress called Qomr, a mound of yellowish brick rising up from the left bank of the turbid river, in whose donjon by long tradition the warlord was obliged to lay his head. But on his return to Atil from the summer hordes, the usurper Buljan ordered that his sukkah be erected on the donjon's roof, with its strategic views of the kagan's palace, the seafront, the Muslim quarter and the steppe, and above all with its relative nearness to the stars, among which his sky-worshiping and uncircumcised ancestors still hunted with infallible gyrfalcons for celestial game.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gentlemen of the Road»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gentlemen of the Road» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gentlemen of the Road» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.