The director listened with half an ear, busy framing with gloved hands an olive tree that looked like the play-thing of a petulant elephant. Eventually rejecting the tree as insufficiently picturesque for his purposes, he drifted over to join us. There we stood, hunched into our coats while Pessoa valiantly lectured on the glories that were Lisbon, a brisk wind out of Antarctica making it difficult to admire the view through watering eyes. Fflytte seemed the most impervious, and the most appreciative, visually devouring the red tile, the white walls, the noble dimensions of the plaza far below, the ruler-sharp line of the Avenida. On the rising hillside across from us, a patch of green among the red tiles indicated a garden at the back of the Teatro Maria Vitória.

Pessoa, dressed in the thinnest coat of us all, methodically worked his way down the central valley of Lisbon: here the skeletal remains of a famous convent, there the lines of the shopping district and the roof of our hotel, across from us the odd construction of an outside lift used to raise pedestrians up yet another of the city’s cliff-like hills. I muttered that the city must have been originally settled by mountain goats, a jest that either Pessoa did not understand or did not appreciate, because after a glance at me, he led us down the esplanade towards the waterfront, where the buildings at our feet grew smaller, their right angles grew skewed, and the streets, to all appearances, disappeared completely.

And there the director froze. He stood with his toes against the stones of the wall, bending his waist forward, his attitude so fervent one expected a vision of the risen Jesú to glisten against the faraway southern shore. A hand shot out, forefinger extended – then, as if leather made an intolerable barrier between himself and the object of his attentions, Fflyte tore off his glove and extended the bare finger, trembling gently with passion, or cold.

“Look!” he breathed.

We looked. At a harbour, a nice large harbour with the ocean off to the right somewhere. We studied the hills across the water, and boats of all sizes and descriptions, sailing or (more often, it being Sunday for fishing-folk as well) resting at anchor. From Fflytte’s attitude, I expected a cavorting whale or mermaid, or someone strolling on the surface of the grey water. I took a closer look at the angle of his pointed digit, then tried again.

“The boat?” Hale asked, after a similar reconsideration of the forefinger. Which words didn’t help me much, since there were perhaps a hundred boats out there, but Fflytte looked up at his cousin with a face lit with the joy and yearning of a young girl cajoling for a Christmas pony.

“Oh, it would be perfect.”

As my eyes continued to examine and reject one floating object after another, my memory dug out and brushed off for my consideration a topic that had been touched upon during our meandering walk to the tram: Fflytte saying that we should need a boat in Morocco for one or two shipboard scenes. However, since this was still Lisbon, and since I knew the director well enough to suspect that his needs changed by the hour, much less the week, I had not inscribed his remark onto my mental to-do list.

However, it had concerned a boat, and there were a lot of boats before me. I cleared my throat. “Er, which …?”

Fflytte whirled on me with an outraged look, as if I had failed to pick out which in a group of otherwise unremarkable girls was his own adorable, beautiful, and in all ways unique fiancée. “ That one!”

“Two masts,” Hale murmured, rather more helpfully.

Having had it both confirmed and narrowed down, I looked along the waterfront until I indeed came to a two-masted sailing boat.

Or what had once been a two-masted sailing boat. At a distance, I could not be certain, but it did not appear to me as if the masts stood quite parallel to each other. And as a non-sailor, I could not be certain, but drunken masts did not strike me as a promising start.

Fflytte whirled, his eyes burning with need. “How do we get down there?” he demanded of Pessoa, who for once seemed prepared for the strange impulses of his temporary employer. He pointed so readily at the exit that he might have been expecting the director’s demand. Fflytte seized the translator’s arm and hurried him towards the exit. I glanced at Hale, whose expression was, as I’d feared, somewhere between irritation and amusement.

“Tell me he’s not serious,” I pleaded.

He looked after the back of his fast-retreating cousin, and the complicated visage settled into a sort of sad affection. “Of course he’s serious, Miss Russell. That’s how Randolph looks when he falls in love.”

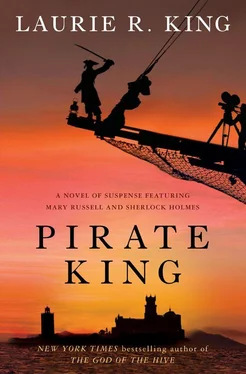

PIRATE KING: I sink a few more ships, it’s true,

Than a well-bred monarch ought to do.

SHE’D BEEN A brigantine, once upon a time – from the Italian for brigand -and if this was love at first sight, love truly was blind.

She was a wreck.

No, she was worse than a wreck: A wreck would at least carry a faint trace of romance from the by-gone days and the glory that was sail.

Her name was Harlequin , and she was every bit the hotchpotch that name suggested. Granted, her lines had once been clean, but that was before she’d been converted into a fishing boat and given an engine and strewn about with lines and props and cabins and God-knows-what-all. An Arab mare with bobbed tail and denuded mane, daubed with spots and hitched to a rag-and-bone cart, wouldn’t have had her beauty more thoroughly hidden than this boat.

But Randolph Fflytte saw it. He saw instantly through twenty years of cart-horse behaviour, two decades of make-shift make-do, thousands of nautical miles of heavy-handed adaptations to her original lines, to the sleek, quick beauty she’d been when she danced down the rollers from her birth dock to slip demurely into the sea.

He stood on the dock and gazed across the intervening water at her, his face transformed. He looked inches taller. I would not have been too surprised if he had stepped off the chewed-up boards and trotted across the oily, debris-clogged water, just to touch her scaley hull.

“But we leave for Morocco in six days!” I protested. Geoffrey Hale and I were standing back, keeping an eye on Fflytte and Pessoa, two unlikely outlines side by side at the edge of the dock nearest the Harlequin . “We’d have to write whatever scenes he wants and rehearse them and then film them – assuming that boat doesn’t founder as soon as three people board it.”

“With any luck, it’ll go down before morning.” Hale sounded no more pleased at the prospect of arranging to film on this floating anachronism than I was. I opened my mouth to offer my services as amateur incendiarist, then reminded myself that revealing unlikely skills was not compatible to an undercover investigation. I changed what I had been about to say.

“Maybe he can shoot whatever scenes he has in mind while it’s at anchor? Draping sheets where the sails are supposed to be?”

My only answer was Hale’s slow sideways glance and raised eyebrow. I had to agree: With a reputation for realism (God, that word!) to protect, bed-sheets would not meet Fflytte’s standards.

With a sigh, I took out my note-pad. “What are we going to need?”

“Pessoa can find out,” Hale answered. “He’s the one who drew Randolph’s attention to the boat; he’s the one who can wade through fish guts to find the owner. By the time he’s finished, he’ll regret not hurrying us past that view-point.”

Hale looked sourly at the two men: Mr Pessoa looked remarkably pleased with himself, smug as any match-maker. It had not yet occurred to him that the racket he heard in the background was the sound of a spanner clanging against the finely tuned machinery of a film-crew.

Читать дальше