During the mid-1920s the tone of Kraus’s writings became more hopeful as he supported the reforms of the Social Democrats, who were constructing a more egalitarian community in Vienna. Recognizing that the war had left a legacy of nationalist resentment and social deprivation, he actively engaged in the political struggle. It was in the sphere of culture that he became most directly involved, for he shared the Austro-Marxist view of “Bildung” (culture and education) as a force for social renewal. His recitals made a significant contribution to socialist cultural politics, as members accustomed to the tedium of party meetings were roused from their slumbers by his captivating performances. His gift for composing and reciting topical verses, inserted into works by Nestroy or Offenbach, revived one of the most potent of popular traditions, using hard-hitting epigrams to clinch the connections between culture and politics.

One of the primary aims of the educational reforms was to remove chauvinistic literature from libraries, and in 1922 a purge was undertaken of books that glamorized militarism, the Habsburg dynasty, and the Catholic Church. Kraus proposed radical new texts for inclusion in school textbooks. In place of the cult of military valour, children should learn about the debilitating effects of war on the civilian population. The need to educate the next generation in an antimilitarist spirit led him to wonder why the reformers had not included any poems from The Last Days of Mankind in their school anthology (F 588–94, 86). This would help to ensure that “little Aryans, when they grow up, would not develop into such big Aryans that they can’t wait for a World War” (F 668–75, 58).

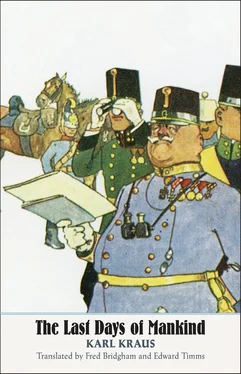

Kraus responded to Hitler’s seizure of power in Germany by composing Dritte Walpurgisnacht (Third Walpurgis Night), an incisive analysis of Nazi atrocities compiled during the summer of 1933. It could not be published until after the defeat of Hitler’s Germany, and there is as yet no English translation. Kraus did not live long enough to witness the annexation of Austria, followed by an even more apocalyptic Second World War. He died in Vienna of natural causes on 12 June 1936 and lies buried in a Grave of Honour. His most eloquent memorial is The Last Days of Mankind . To mark the play’s centenary we now present the complete text in English for the first time, incorporating translation strategies that are summarized in our Afterword and elucidated in the Glossary.

Notes

1. References to Die Fackel , ed. Karl Kraus (Vienna, 1899–1936), are identified by the abbreviation F followed by the issue and page number.

2. For a comprehensive account of the apocalyptic themes that shaped Kraus’s career, see Edward Timms, Karl Kraus — Apocalyptic Satirist , Part 1: Culture and Catastrophe in Habsburg Vienna (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986), and Part 2: The Post-War Crisis and the Rise of the Swastika (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2005).

3. See Paul Reitter, The Anti-Journalist: Karl Kraus and Jewish Self-Fashioning in Fin-de-Siècle Europe (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

4. For an English translation of “In dieser großen Zeit”, see In These Great Times: A Karl Kraus Reader , ed. Harry Zohn (Montreal: Engendra Press, 1976; repr. Manchester: Carcanet, 1984), 70–83. Much as we admire the pioneering translations of Harry Zohn, we feel that “In This Age of Grandeur” comes closer to capturing the resonance of Kraus’s title.

5. Arthur Ponsonby, Falsehood in War-Time: Containing an Assortment of the Lies Circulated Throughout the Nations During the Great War (London: Garland, 1928), 11; for an update, see Phillip Knightley, The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero, Propagandist and Myth-Maker from the Crimea to Iraq (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004).

6. www.newyorker.com/news/amy-davidson/shattered-school-in-gaza-2 ( New Yorker , July 30, 2014; viewed August 2014).

7. G. K. A. Bell, “Obliteration Bombing”, in Bell, The Church and Humanity 1939–1946 (London and New York: Longmans, 1946), 129–41.

8. Kant’s Schriften (Akademieausgabe), vol. 8 (Berlin, 1912), 346 and 356; cf. Kant’s Political Writings , ed. Hans Reiss, tr. H. B. Nisbet (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970), 96 and 104.

The performance of this drama, which would take some ten evenings in terrestrial time, is intended for a theatre on Mars. Theatregoers on planet earth would find it unendurable. For it is blood of their blood and its content derives from the contents of those unreal unthinkable years, out of sight and out of mind, inaccessible to memory and preserved only in bloodstained dreams, when operetta figures played out the tragedy of mankind. The action is likewise without heroes, fractured and improbable, as it picks its way through a hundred scenes and hells. The humour is no more than the self-reproach of an author who did not lose his mind at the thought of surviving, with his faculties intact, to bear witness to such profane events. He alone, compromised for posterity by his involvement, has a right to this humour. As for those contemporaries who allowed the things transcribed here to happen, let them subordinate the right to laugh to the duty to weep.

The most improbable actions reported here really occurred. Going beyond the realm of Schillerian tragedy, I have portrayed the deeds they merely performed.* The most improbable conversations conducted here were spoken word for word; the most lurid fantasies are quotations. Sentences whose insanity is indelibly imprinted on the ear have grown into the music of time. The document takes human shape; reports come alive as characters and characters expire as editorials; the newspaper column has acquired a mouth that spouts monologues; platitudes stand on two legs — unlike men left with only one. An unending cacophony of sound bites engulfs a whole era and swells to a final chorale of calamitous action. Those who have lived among men, and outlived them — as actors and mouthpieces of an age that has exchanged flesh for blood and blood for ink — have been transformed into shadows and puppets and re-created as dynamic nonentities.

Spectres and wraiths, masks of the tragic carnival, necessarily have real-life names, for nothing is fortuitous in an age conditioned by chance. This gives no one the right to regard the action as a local affair. Even what occurs at the corner where Vienna’s Ringstrasse meets the Kärntnerstrasse is controlled from some point in the cosmos. Let those who have weak nerves, even if strong enough to endure those times, turn their backs on our play. One should not expect the age when such events could occur to treat this conversion of horror into words as other than a joke, especially when the most gruesome dialects resound from the depths of the homely territory it plumbs, or to think of what has just been lived through and outlived as other than an invention. An invention whose contents they despise.

Far greater than the infamy of war is that of men who want to forget that it ever took place, although they exulted in it at the time. War is no longer a live issue for those who have outlived it, and while the masks parade on Ash Wednesday, they do not want to be reminded of one another. It’s all too easy to understand the disenchantment of an epoch forever incapable of experiencing such events, or grasping what’s been experienced, compounded by the failure to be convulsed by its collapse. It is an age whose actions exclude the impulse for atonement, but it has an instinct for self-preservation that enables it to close its ears to the gramophone record of its heroic melodies, and a readiness for self-sacrifice that will enable it to strike them up again should the occasion arise. For the continuing existence of war appears least inconceivable to people whom the slogan “Now we are at war” enables to commit and endorse every possible infamy; but the reminder “Now we were at war!” disturbs the well-earned rest of the survivors.

Читать дальше