Но самым знаменитым в России стихотворением Теннисона стала «Годива». Баллада, основанная на старинном предании о доброй леди Годиве, которая, чтобы спасти земляков от непосильных поборов, согласилась проехать нагой по улицам своего города. В этом стихотворении счастливо сошлись туманный средневековый колорит и позитивное «народническое» содержание. «Годива» угодила всем: и некрасовскому «Современнику» 1859 года (перевод М. Михайлова), и эстетам Серебряного века (перевод И. Бунина, 1906). Недаром Осип Мандельштам через много лет вспоминал в стихотворении «С миром державным я был лишь ребячески связан…»:

Не потому ль, что я видел на детской картинке

Леди Годиву с распущенной рыжею гривой,

Я повторяю еще про себя под сурдинку:

Леди Годива, прощай… Я не помню, Годива.

После революции в Советской России Теннисон за свои консервативные взгляды и «связь с британским империализмом», естественно, стал персоной non grata . Но одна его строка, заключительная строка «Улисса» — без имени автора, — сделалась широко известной благодаря В. Каверину и его роману «Два капитана». Одна только строка, но зато какая:

Бороться и искать, найти и не сдаваться!

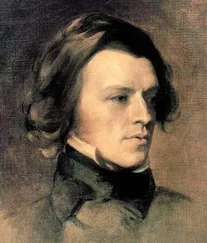

Сын Теннисона, Хэллем, запомнил со слов отца, как тот мальчуганом, еще не умеющим читать, бывало, выбегал из дома в непогоду и, широко расставив руки, кричал в необъяснимом восторге: «Я слышу голос, говорящий в ветре!»

В конечном итоге «все оправдалось и сбылось». Он прошел и медные трубы славы, и посмертное непонимание. Весы выровнялись, роли определились. Великий поэт узнается по тому, сколь прочным звеном он входит в цепь родного языка и поэзии. Альфред Теннисон — прочное звено. Истинная предтеча символистов, сновидец, путешественник по золотым мирам прошлого, предвестник будущего.

Он поет о том, каким будет мир,

Когда годы и время пройдут.

The rain had fallen, the Poet arose,

He pass’d by the town and out of the street,

A light wind blew from the gates of the sun,

And waves of shadow went over the wheat,

And he sat him down in a lonely place,

And chanted a melody loud and sweet,

That made the wild-swan pause in her cloud,

And the lark drop down at his feet.

The swallow stopt as he hunted the fly,

The snake slipt under a spray,

The wild hawk stood with the down on his beak,

And stared, with his foot on the prey,

And the nightingale thought, ‘I have sung many songs,

But never a one so gay,

For he sings of what the world will be

When the years have died away.’

Ливень схлынул, и вышел Поэт за порог,

Миновал дома, городской предел,

Ветерок подул от закатных туч,

Над волнами ржи, как дрожь, пролетел.

А Поэт нашел одинокий холм

И так звонко, так сладко песню запел —

Дикий лебедь заслушался в небесах,

Наземь жаворонок слетел.

Стриж забыл на лету догонять пчелу,

Змейка юркнула в свой приют,

Ястреб с пухом жертвы в клюве застыл,

Он скорей растерян, чем лют;

Соловей подумал: «Мне так не спеть,

На земле так, увы, не поют —

Он поет о том, каким будет мир,

Когда годы и время пройдут».

Г. Кружков

‘Mariana in the moated grange’ —

Measure for Measure

With blackest moss the flower-plots

Were thickly crusted, one and all:

The rusted nails fell from the knots

That held the pear to the gable-wall.

The broken sheds look’d sad and strange:

Unlifted was the clinking latch;

Weeded and worn the ancient thatch

Upon the lonely moated grange.

She only said, ‘My life is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said;

She said, ‘I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!’

Her tears fell with the dews at even;

Her tears fell ere the dews were dried;

She could not look on the sweet heaven.

Either at morn or eventide.

After the flitting of the bats,

When thickest dark did trance the sky,

She drew her casement-curtain by,

And glanced athwart the glooming flats.

She only said, ‘The night is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said;

She said, ‘I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!’

Upon the middle of the night,

Waking she heard the night-fowl crow:

The cock sung out an hour ere light:

From the dark fen the oxen’s low

Came to her: without hope of change,

In sleep she seem’d to walk forlorn,

Till cold winds woke the grey-eyed morn

About the lonely moated grange.

She only said, ‘The day is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said;

She said, ‘I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!’

About a stone-cast from the wall

A sluice with blacken’d waters slept,

And o’er it many, round and small,

The cluster’d marish-mosses crept.

Hard by a poplar shook alway,

All silver-green with gnarled bark:

For leagues no other tree did mark

The level waste, the rounding gray.

She only said, ‘My life is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said;

She said, ‘I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!’

And ever when the moon was low,

And the shrill winds were up and away,

In the white curtain, to and fro,

She saw the gusty shadow sway.

But when the moon was very low,

And wild winds bound within their cell,

The shadow of the poplar fell

Upon her bed, across her brow.

She only said, ‘The night is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said;

She said, ‘I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!’

All day within the dreamy house,

The doors upon their hinges creak’d;

The blue fly sung in the pane; the mouse

Behind the mouldering wainscot shriek’d,

Or from the crevice peer’d about.

Old faces glimmer’d thro’ the doors,

Old footsteps trod the upper floors,

Old voices called her from without.

She only said, ‘My life is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said;

She said, ‘I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!’

Читать дальше