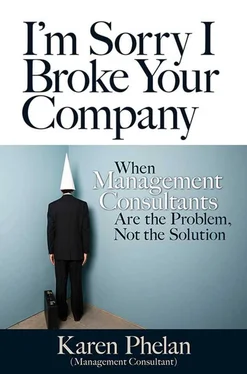

Karen Phelan - I'm Sorry I broke Your Company

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Karen Phelan - I'm Sorry I broke Your Company» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: San Francisco, Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Жанр: management, popular_business, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:I'm Sorry I broke Your Company

- Автор:

- Издательство:Berrett-Koehler Publishers

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- Город:San Francisco

- ISBN:978-1-60994-740-8; 978-1-60994-741-5

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

I'm Sorry I broke Your Company: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «I'm Sorry I broke Your Company»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

I'm Sorry I broke Your Company — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «I'm Sorry I broke Your Company», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The reason why businesses love measures is because they mistakenly believe that measures are real, hard data. Another misguided management mantra, «The numbers don't lie,» forgets that people are the ones monitoring, collecting, configuring, and reporting the measures. Measures are not objective. Measures lie all the time, even financial ones. Finance is not a science but a matter of opinion; the rules are only generally accepted accounting principles (the United States uses GAAP versus international financial reporting standards [IFRS]) and can differ from country to country. What goes into a unit cost, or a capital expenditure versus an expense, or what qualifies as an asset can vary from company to company and can be manipulated to paint the desired picture. An extreme example is the financial games Enron played.

For one client, I was asked to improve the company's manufacturing costs, which had recently ballooned. Nothing at the plant had changed except for the way overhead costs were allocated. Bundling up overhead costs and divvying them up by space occupied or by number of employees is not a true representation of what something costs. Yet most companies use some kind of overhead allocation formula because it is convenient. It takes too much time to figure out which products use the most electricity or what department consumes the most network bandwidth. What something costs is a matter of convention rather than a «hard» number. Revenues are harder to fudge, but when a sale is booked is a matter of convention. This can make a difference in meeting those quarterly targets.

You can play lots of games in accounting and financial reporting, and when you get to the squishier measures, there is even more room for creativity. When does the clock start on new product development cycle time — when the product is an idea or when it has a budget or when a project manager gets assigned? Are classroom supplies included in the training dollars per employee? Does defective product quantity include the pieces that were reworked to meet the specifications? See how much fun you can have? Even better, you can change the definitions every year to show improvement. Include the rework one year and exclude it the next, and, voila, defective parts show a dramatic decline! (But make sure you include a tiny footnote on the chart to document the change in measurement. You don’t want to be accused of fraud!)

In reaction to all this game playing, companies often implement countermeasures. These are additional measurements that act as a balance to the original metric designed to achieve the strategic goal. Lets revisit the sales function where sales commissions are based on target revenue volumes at the expense of profit margins. The next iteration of the game includes a profitability measure. Now we have salespeople pushing the high-margin products, which seems like a good thing, except they are pushing them instead of other, cheaper products. The result is angry customers who have been bullied into buying pricier items. Annoyed, they start to buy from competitors. Or in reverse, lets add a customer satisfaction index to the mix instead of profitability. Now the salespeople have no incentive to sell products at a reasonable margin. Selling at or near cost improves both sales volumes and customer satisfaction even though it hurts the company. So the only thing that makes sense is to measure revenues, profitability, and customer service. Now we have increased returns! Customers are motivated to buy with a no-questions-asked-free-returns policy. So add customer returns to the mix. After a few rounds of this game, the result is a laundry list of measures and targets. The focus on and priority of the strategic objectives are gone, and the only work that gets accomplished is the measurements. Worse, long-term goals or work that isn’t covered by an annual measure falls by the wayside. Any incentive to invest in the long-term future of the company is gone.

These examples show the game playing and willful manipulation that occur in these measurement systems — a worst-case scenario. Yet even when no game playing or manipulation is involved and the people being measured are compliant — a best-case scenario— these trickle-down measurement systems do the opposite of what is intended. I learned a very interesting lesson about conflicting metrics from a big supply-chain process reengineering project. The client had typical supply-chain problems — lots of inventory, long lead times, many unfulfilled orders, and unhappy customers. A few weeks into the engagement, the flagship plant burned down, severely diminishing the amount of product, throwing everyone into a panic. Rather than continue with the project, some of the consultants were asked to help manage the crisis. During the ensuing weeks, the consultants established a process for contacting customers, negotiating orders and due dates, working with contract suppliers, and shipping to meet delivery dates. As expected, the surplus inventory was eliminated, but additionally, the lead times decreased, orders arrived as planned, customers paid earlier, and both customer satisfaction and profitability improved, albeit at reduced revenues.

The bottom line improved because the margins on the smaller sales revenues increased and the costs of carrying inventory and accounts receivables decreased. These results blew me away— all the improvements without the process reengineering. At the time, I wasn’t sure why, but over the next few years, I continued to work in supply chain and eventually figured out why those large, segmented projects rarely showed the improvements we expected. Here is a typical supply chain, the typical measures, and the consequences of rewarding those measures. I am assuming no game playing occurs.

Sales —Salespeople are responsible for selling the goods and obtaining the customer orders. As I've already discussed, most sales functions have quarterly sales quotas, resulting in a big push to meet the quota at the end of quarter when it looks like it won't be met. Customers who are planning to place orders in the beginning of the next quarter are given rebates or other promotions to place them before quarter end. Besides the peak at the end of the quarter, this causes a trough at the beginning of the next quarter.

Result: Sales representatives are creating artificial spikes and troughs in demand and may be eating into profit margins with promotions. The dreaded supply-chain bullwhip effect of spikes in demand actually starts in-house.

Order entry /customer service —Each order gets processed either by a computer or by a human. Either way, the purpose of this function is to ensure the order information is correct and determine when the order can be filled. Although some companies use processing times as their metrics, most companies have learned the dangers of quantity measures (filling lots of orders quickly but incorrectly) and prefer quality metrics like order accuracy. Accuracy is important because it can be costly to fill the wrong order, process a return, and then fill it again correctly. Plus, incorrect fulfillment tends to annoy customers.

Result: Customer service representatives are incentivized to verify that all the order information is correct, erring on the side of caution and possibly double-checking with the customer or sales rep, which is at odds with minimizing the overall order lead time.

Warehouse —If product inventory is on hand, the warehouse picks the product and stages it for shipping. Inventory management is a delicate balance. Too much inventory means that lots of money is tied up in unsold product that incurs warehousing costs and risks obsolescence from sitting too long on the shelves. Too little inventory could mean stockouts, where customer orders cant be filled until more product is made, risking the loss of sales. Inventory managers typically determine how much stock to keep on hand by calculating how long it takes to make the product plus how long it takes to process an order (order lead time) and using a fudge factor based on the variability in demand. If product demand does not fluctuate much, they don’t need much safety stock to cover the variation. However, if demand is irregular, they need to store enough product to cover the peaks in demand. If it takes a long time to make the product, they again need to store a lot of inventory. However, more inventory means more carrying costs and more risk of obsolescence — hence, the delicate balance. Their ideal world would be to have stable demand and short order lead times.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «I'm Sorry I broke Your Company»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «I'm Sorry I broke Your Company» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «I'm Sorry I broke Your Company» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.