Stefan Zweig - The Royal Game

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Stefan Zweig - The Royal Game» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Языкознание, Критика, на немецком языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Royal Game

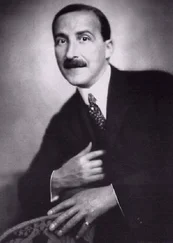

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:9783962172770

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Royal Game: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Royal Game»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Royal Game — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Royal Game», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

One winter evening while the two players were engrossed in their daily game, the jingle of sleigh bells came from the village street, approaching with greater and greater speed. A peasant, his cap dusted with snow, stumped in hurriedly—his old mother was dying, and he wanted the parson to hurry so that he would be in time to administer the last rites. The parson followed without hesitation. As he was leaving, the constable, who was still drinking his beer, lit a fresh pipe and was preparing to pull on his heavy top boots when he noticed that Mirko’s gaze was riveted on the chessboard with the unfinished game.

“So, you want to play it out, do you?” he said jokingly, completely convinced that the sleepy boy did not know how to move a single piece on the board correctly. The boy looked up shyly, then nodded and took the parson’s chair. After fourteen moves the constable had been beaten, and, he had to admit, through no careless error of his own. The second game ended no differently.

“Balaam’s ass!” exclaimed the astounded parson upon his return, explaining to the constable, who was not so well versed in the Bible, that by a similar miracle two thousand years ago a dumb creature had suddenly found the power of intelligent speech. In spite of the late hour, the parson could not refrain from challenging his semiliterate famulus. Mirko beat him too with ease. He played doggedly, slowly, stolidly, without once lifting his bowed broad forehead from the board. But he played with unassailable certainty; during the days to come neither the constable nor the parson was able to win a game against him. The parson, who knew better than anyone how backward his pupil was in other respects, now became curious in earnest as to how far this one strange talent might withstand a more rigorous test. After having Mirko’s unkempt blond hair cut at the village barber’s, to make him somewhat presentable, he took him in his sleigh to the small neighboring city where, in a corner of the café in the main square, there were chess enthusiasts for whom (as he had found) he himself was no match. There was no small stir among them when the parson pushed the tow-headed, rosy-cheeked fifteen-year-old in his fur-lined sheepskin jacket and heavy, high-top boots into the coffeehouse, where, ill at ease, the boy stood in a corner with shyly downcast eyes until someone called him over to one of the chess tables. Mirko lost against his first opponent, because he had never seen the “Sicilian opening” in the good parson’s game. He drew the second game, against the best player. From the third and fourth games on, he beat all his opponents, one after another.

Now it is rare indeed that anything exciting happens in a small provincial city in Yugoslavia, and the first appearance of this rustic champion caused an instant sensation among those in attendance. There was unanimous agreement that the boy wonder must definitely remain in the city until the next day, so that the other members of the chess club could be assembled and especially so that old Count Simczic, a chess fanatic, could be reached at his castle. The parson looked at his ward with a pride that was quite new, but, for all his joy of discovery, he still did not wish to neglect his duty to perform the Sunday services; he declared himself willing to leave Mirko behind for a further test. The young Czentovic was put up in the hotel at the chess club’s expense and saw a water closet that evening for the first time. The next afternoon, the chess room in the café was jammed. Mirko, sitting motionless in front of the board for four hours, defeated one player after another without uttering a word or even looking up; finally a simultaneous game was proposed. It took some time to make the ignorant boy understand that in a simultaneous game he would be the only opponent of a range of players. But once Mirko had grasped this, he quickly warmed to the task. He moved slowly from table to table, his heavy shoes squeaking, and in the end won seven of the eight games.

At this point great deliberations began. Although this new champion was not strictly speaking a resident, regional pride was keenly aroused just the same. Perhaps the small city, whose presence on the map had hardly ever been noticed, could finally boast of an international celebrity. An agent by the name of Koller, who otherwise represented nobody but chanteuses and cabaret singers employed at the garrison, announced that, in return for a year’s subsidy, he would arrange to have the young man given professional training in the art of chess by an excellent minor master of his acquaintance in Vienna. Count Simczic, who in sixty years of daily play had never encountered such a remarkable opponent, immediately underwrote the amount. That day marked the beginning of the astonishing career of the boatman’s son.

After half a year Mirko had mastered all the secrets of chess technique, though with a peculiar limitation that was later to be much noted and ridiculed in professional circles. For Czentovic never managed to play a single game by memory alone—“blind,” as the professionals say. He completely lacked the ability to situate the field of battle in the unlimited realm of the imagination. He always needed to have the board with its sixty-four black and white squares and thirty-two pieces physically in front of him; even when he was world-famous, he carried a folding pocket chess set with him at all times so that, if he wanted to reconstruct a game or solve a problem, he would be able to examine the positions of the pieces by eye. This failing, in itself minor, betrayed a lack of imaginative power and was the subject of lively discussion in elite circles, of the sort that might be heard among musicians if a prominent virtuoso or conductor had proven himself unable to play or conduct without an open score. But this strange idiosyncrasy did nothing whatever to slow Mirko’s stupendous climb. At seventeen he had already won a dozen prizes, at eighteen the Hungarian Championship, and at twenty he was champion of the world. The most audacious grandmasters, every one of them infinitely superior to him in intellectual gifts, imagination, and daring, fell to his cold and inexorable logic as Napoleon to the ponderous Kutuzov or Hannibal to Fabius Cunctator (who, according to Livy’s report, displayed similar conspicuous traits of phlegm and imbecility in childhood). Thus it happened that the illustrious gallery of chess champions, including among their number the most varied types of superior intellect—philosophers, mathematicians, people whose natural talents were computational, imaginative, often creative—was for the first time invaded by a total outsider to the intellectual world, a dull, taciturn peasant lad, from whom even the craftiest newspapermen were never able to coax a single word of any journalistic value. Of course, what Czentovic denied the newspapers in the way of polished sentences was soon amply compensated for in anecdotes about his person. For the instant he stood up from the chessboard, where he was without peer, Czentovic became an irredeemably grotesque, almost comic figure; despite his solemn black suit, his splendid cravat with its somewhat showy pearl stickpin, and his painstakingly manicured fingernails, his behavior and manners remained those of the simple country boy who had once swept out the parson’s room in the village. To the amusement and annoyance of his professional peers, he was artless and almost brazen in extracting, with a miserly, even vulgar greed, what money he could from his talent and fame. He traveled from city to city, always staying in the cheapest hotels, he played in the most pathetic clubs as long as they paid his fee, he permitted himself to appear in soap advertisements, and even—ignoring the mockery of his competitors, who knew quite well that he couldn’t put three sentences together—sold his name for use on the cover of a Philosophy of Chess which had actually been written for the enterprising publisher by an insignificant Galician student. Like all headstrong types, Czentovic had no sense of the ridiculous; ever since his triumph in the world tournament, he considered himself the most important man in the world, and the awareness that he had beaten all these clever, intellectual, brilliant speakers and writers on their own ground, and above all the evident fact that he made more money than they did, transformed his original lack of self-confidence into a cold pride that for the most part he did not trouble to hide.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Royal Game»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Royal Game» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Royal Game» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.