‘I can’t be bothered,’ we might say, and it’s likely to make people cross. And, most of the time, and probably with ill grace, we somehow end up doing whatever it is that needs doing.

That’s the problem with ‘I can’t be bothered.’ It’s a blunt phrase that, just at a time when you really don’t feel like taking responsibility, puts you right in the firing line. It’s not what you want to say: the problem is with the suddenly unreasonable demand that is being made, not with your own response to it. What you want is a phrase that throws the blame where you instinctively know it belongs – on the person who has made the request, on the action itself, on the entire world if necessary, but not on you.

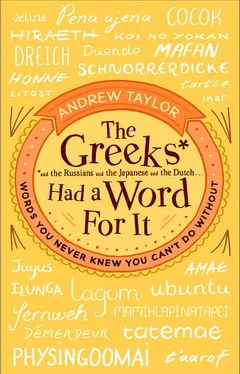

The Chinese have an invaluable little word – mafan ( MAH-FAHN ). Some people say that if you learn only one word of Chinese, then mafan is the one – although that could be a reflection on the frustrations of Chinese bureaucracy rather than a comment on the word itself.

It means something you’ve been asked to do is too bothersome – just too much trouble. It’s frustrating, annoying and completely unreasonable that you have been asked. But the important thing about it is that it focuses the blame where it should be – not on you.

Its applications are almost infinite. A tax form may be too complicated for anyone but a Professor of Incomprehensible Logic to understand, and you would ask, ‘Why is this so mafan ?’ Or it could be used against you in a restaurant, when you ask if you could have the noodles but without the meat – ‘No, that’s too mafan for the chef.’

And the beauty of it is that it’s not an exclusively dismissive or negative word. You can apologize – probably insincerely, but no one’s to know – for causing someone so much mafan . Tack -ni , meaning ‘you’, on to it and it is suddenly an extremely polite and courteous way of asking a question, more or less equivalent to ‘Excuse me, may I trouble you?’ So you might say, ‘ Mafan-ni , could you tell me the way to the station?’

But we do politeness well in English already. We have plenty of ingratiating little phrases with which to butter people up when we want them to do us a favour. It’s that subtle evasion of responsibility that we need, that deft avoidance of blame. ‘Shouldn’t you take the dog for a walk?’ ‘ Mafan .’

It shouldn’t work, of course. It would seem to drip with the same sort of dismissive contempt that an idle teenager can pour over the words ‘Whatever,’ or ‘Yeah, right.’ But the Chinese seem to manage mafan quite successfully. Perhaps we should give it a go in English.

Term of endearment for a child who asks a lot of questions – perhaps too many questions

‘Yes, but why?’

As anyone who has children will know, these words bring a thrill of joy to our hearts the first time we hear them, because we are new parents, and idealistic, and optimistic, and we want to encourage a healthy curiosity in our offspring. And so we offer a carefully crafted and well-thought-out explanation, not too simple but pitched at exactly the right level for our child’s understanding.

‘Yes, but why?’

The next explanation has a slightly puzzled edge to it. We thought we’d answered that one the first time. So we try again.

‘Yes, but why?’

The third explanation is probably a little shorter and slightly less carefully crafted. It might even have a barely perceptible edge of frustration. There is, after all, a newspaper that we want to read, or a programme to watch, or a car to polish.

‘Yes, but why?’

The fourth explanation is even shorter. It may well contain an unfortunate phrase like ‘For God’s sake!’ in it, or possibly something even less acceptable. And so it goes on, six or seven times or more, until, to our eternal shame, we come through clenched teeth to the final and unavoidable, ‘Because I say so!’

The diminutive suffix - uchka makes clear that it’s meant affectionately.

This child with the healthy curiosity that we were once so keen to encourage is what the Russians would call a pochemuchka ( POH-chay-MOO-chka ) – someone who asks too many questions. It comes from the Russian word pocemu (POH-chay-MUH) , which means ‘Why?’, and was first used in a popular Soviet-era children’s book [5] Boris Zhitkov, Što ja vídel or What I Saw , ed. Richard L. Leed and Lora Paperno (Indiana University: Slavica Publishers, 1988).

whose hero was a little boy given the nickname Alyosha Pochemuchka because he was never satisfied with the answers he got. The book was published in 1939, when Stalin was at the height of his power, so discouraging children from trying to find out too much was probably a wise move for cautious parents, but it’s generally the sort of light-hearted put-down that might be expressed in English with a warning like ‘Curiosity killed the cat.’

The diminutive suffix - uchka makes clear that it’s meant affectionately, but do we really need a word like this? Once we’ve got over the frustration of a long train of ‘Yes, but whys’, we don’t really want to tell our children not to ask too many questions.

But the term doesn’t have to be applied only to children. It may not be a clever way to address a Russian policeman who is asking you for details of where you’ve been and whom you’ve seen, but assimilated into English it might be a very useful word to use to a local government official who won’t go away, or anyone in authority for whom it would be much less aggressive than a bad-tempered ‘Mind your own business.’ That patronizing -uchka at the end, the verbal equivalent of patting the person you are speaking to on the head, might also give a very pleasant feeling of superiority.

Someone very skilled at getting others to pay out of a sense of duty

Make the mistake of getting out of a taxi without leaving a big enough tip and you may hear the taxi driver mutter under his breath, ‘ Schnorrer !’ ( SHNORR-uh ). This, you will understand instinctively, is not a compliment.

Originally, the word was used by Jews about Jews, describing a dishonest beggar – a man, for example, who might dress as a gentleman, talk with all the pretensions of a scholar and treat his companion with expansive and condescending civility, but who would still ask for the loan of the price of a phone call. And then ask again. And again for something else.

Such a man would give elaborate and generally entirely imaginary reasons for asking for help – he might have been robbed, his house might have burned down, or he might find himself temporarily embarrassed at a moment when he needs to pay to get his car mended, settle an annoying bill, or offer assistance to a relative who has fallen on hard times. In any case, since both the schnorrer and generally his victim as well are Jewish, there is an overriding moral duty to help him. The more emotional and affecting the story, the better.

A particular kind of schnorrer , the literary schnorrer , might offer copies of a book he has written – always a literary masterpiece, in which he has selflessly invested years of hard and unrewarded work – in return for whatever gift of money the wealthy recipient thinks appropriate. And if the gift is not large enough, the schnorrer is likely to make it very clear that he is unimpressed.

Rather than sitting at the roadside asking for alms, the schnorrer engages with his target, giving the impression that he expects support as of right and is actually conferring a favour by offering the opportunity to give him money or goods. The frequent translation ‘beggar’ fails to reflect the impudence and presumption of the true schnorrer , whose shameless audacity is best summed up in another Yiddish word, chutzpah ( HOOT-spa ). Other words like ‘sponger’, ‘chiseller’ or ‘freeloader’ miss the all-important element of entitlement, while ‘con man’ or ‘confidence trickster’ do not include the sense of duty that the true schnorrer seeks to instil in his victim.

Читать дальше