Okrand, who has a Ph.D. in linguistics, came to be the creator of Klingon through a happy accident involving the 1982 Academy Awards. At the time, he was working for the National Captioning Institute (where he still works), developing methods for the production of real-time closed-captioning for live television. That year’s Oscars presentation, the year of Chariots of Fire and On Golden Pond , was the first major live closed-captioned event. “I arrived in Hollywood a week before the broadcast, and they weren’t ready for me yet. I had nothing to do, so I called an old friend, who happened to work for Paramount. While we were having lunch there at the commissary, a secretary for the associate producer of Star Trek II came by, and my friend introduced me, mentioning that I was a linguist. The secretary said they happened to be looking for a linguist. They needed a few lines of dialogue in Vulcan [the language of Mr. Spock] for the movie, and I think an arrangement with another linguist had just fallen through. I thought it sounded like fun, so I asked when did they need it? End of the week.”

Despite his other obligations Okrand came through on time and skillfully—the scene, between Leonard Nimoy and Kirstie Alley, had been filmed in English, and he had to create lines that could be dubbed over their mouth movements in a believable way—so two years later, when the production team of Star Trek III wanted some scenes in Klingon, Okrand was their go-to linguist. This time he was not constrained by preexisting mouth movements—the actors would be filmed speaking Klingon—but there were two other preexisting conditions he had to take into account. The first was the existence of a few words of Klingon already invented by James Doohan (the actor who played Scotty) for a short scene in the first Star Trek movie. He had to incorporate those lines of Klingon into his own language. Second, he knew the language was supposed to be tough sounding, befitting a warrior race—which he achieved through the preponderance of back-of-the-throat sounds and the intentional absence of small-talk greetings such as “Hello.” (The closest translation in Klingon is nuqneH —“What do you want?”)

Okrand did not just make up a list of words. Knowing that fans would be watching closely, he worked out a full grammar with great attention to detail. Klingon both flouts and follows known linguistic principles, and its real sophistication lies in the balance between the two tendencies. It gets its alien quality from the aspects that set it apart from natural languages: its phonological inventory of sounds that don’t normally occur together, its extremely rare basic word order of OVS (object-verb-subject). Yet at the same time it has the feel of a natural language. A linguist doing field research among Klingon speakers would be able to work out the system and describe it with the same tools he would use in describing a remote Amazon language.

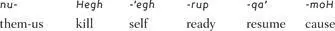

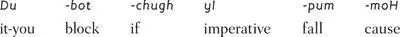

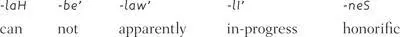

He would quickly deduce, for example, that Klingon is an agglutinating language. Such languages, like Hungarian and Finnish, build words by affixing units that have grammatical meanings to roots, one after the other. In these languages, entire phrases can be expressed in single words. This is how the Klingon proverb “If it is in your way, knock it down” can be expressed in only two words: “ Dubotchugh yIpummoH .” The words are composed of smaller meaningful units:

“If it blocks you, cause it to fall!”

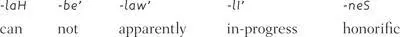

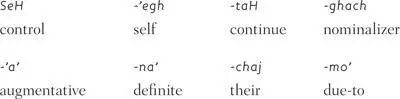

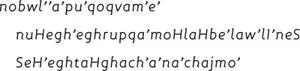

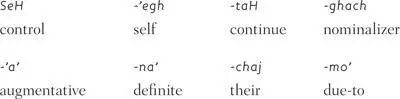

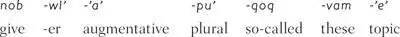

Klingon has twenty-six noun suffixes, twenty-nine pronominal prefixes, thirty-six verb suffixes, two number suffixes, a phrasal topicalizing suffix, and an interrogative suffix. Words have the potential to be very long. The Klingon Language Institute publishes a journal called HolQeD (Language Science, or Linguistics), which held a contest asking readers to come up with the longest possible three-word Klingon sentence. The winning entry, from David Barron:

“The so-called great benefactors are seemingly unable to cause us to prepare to resume honorable suicide (in progress) due to their definite great self-control.”

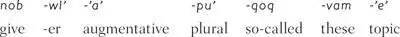

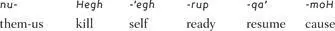

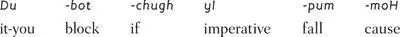

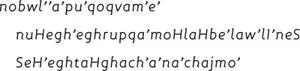

The sentence contains three roots (give, kill, control) and twenty-three affixes. Here is the breakdown:

“

“

As for these so-called great benefactors,”

“they are apparently unable to cause us to prepare to resume honorable suicide (in progress)”

“due to their defi nite great self- control.”

The functions of these affixes are common, from a linguistic point of view. The representation of causation (- moH ) or verbal aspects such as “in progress” (-lI') by verbal suffixes is routine in the language world. The use of an augmentative suffix (-‘ a ’) to convey literal or figurative largeness of the root to which it attaches occurs in languages as familiar as Italian, where the augmentative - one makes padre (father) into padrone (boss, master, big daddy). The - law ' ending in the second word belongs to a class of suffixes called evidentials, used in languages such as Turkish, which qualify statements according to how strongly the speaker can attest to their validity. Honorifics (- neS ), used to recognize superior social status in the person being spoken to or about, are a part of Korean and Japanese.

The nu- that attaches before the verb “to kill” in the second word is part of a complex verb-agreement system that uses prefixes to show who did what to whom. Most people are familiar with a system that uses word endings that indicate who is doing the verb. For example, in Spanish, the -o ending on a verb like hablar (to speak) indicates a first-person-singular subject ( hablo —“I speak”), while the - amos ending indicates a first-person-plural subject ( hablamos —“we speak”). Klingon has such affixes, but they attach before rather than after the verb root, and instead of having six or seven of them, like most Romance languages, it has twenty-nine. The prefixes proliferate because they indicate person and number not only of the subject (who is doing) but also of the object (who is being done to). For example, qalegh means “I see you,” and vIlegh means “I see them”; cholegh means “you see me,” and Dalegh means “you see them.” This type of system is unusual in the realm of languages that people typically study, but not as a general possibility for language.

Subject and object agreement by prefix is quite common, for example, in the Native languages of North America. However, it is not a feature of Mutsun, a West Coast language of the Utian family and the subject of Okrand’s dissertation. Many have speculated that Klingon is based on the Native languages that Okrand studied as a linguist. “I used some features from other West Coast languages, like the ‘tlh’ sound, for example,” said Okrand, “but my basic strategy was to switch sources whenever it started becoming too much like any one language in particular.” This strategy explains my reaction, as a linguist, to Klingon: it is completely believable as a language, but somehow very, very odd.

Читать дальше

“

“