The Blisses set up a photography and moviemaking business in Shanghai’s bustling Jewish community. Over twenty thousand Jews who could not get visas for anywhere else had poured into Shanghai in the early years of the war, and they brought their European way of life with them—filling the streets with cafés, concert halls, and Yiddish newspapers. But Charles, as he puts it, “went ‘oriental’” He became fascinated with “those queer and mysterious Chinese characters” when he saw them “at night in thousands of multi-coloured neon tubes filling the sky and making it a beautiful sight out of a fairy tale.”

He hired a teacher and learned some characters, and he noticed, with astonishment, that when he recognized the characters on a shop sign or a newspaper headline, he read them off in his own language, not in Chinese. “Later on,” he says, “the familiar words of my language disappeared and I could visualize directly the real things depicted by the signs.” He thought he had discovered a potential universal language, a direct line to concepts. But the Chinese system was too complicated and arbitrary. Most of the symbols didn’t look anything like the things they were supposed to represent, so it was too hard to learn. After a year of study, he gave up trying, and he started working on a new invention—a better, simpler system of pictorial symbols, “a logical writing for an illogical world.”

Such a language, he thought, would not just enable people of different nations to communicate easily with each other, but it would also free their minds from the awful power of words. Bliss had seen how Hitler’s slogans made people believe that lies were true. Propaganda—mere words—had instigated terrible acts. Such misuse of language would be impossible, he thought, in a “logical” system of symbols that represented the natural truth. One could not get away with malicious manipulation of words in such a system, because inconsistencies and falsehoods would be instantly exposed. Here was an invention, Bliss thought, that would benefit humanity more than any invention before it.

At the end of the war Charles and Claire immigrated to Australia, where they settled in the suburbs of Sydney. They were full of excitement about their future. “We felt that the scholars of the Western world would receive me and my work with open arms. We were sure that the University of Sydney would offer me a place to work out the primers and textbooks for this wonderful idea.” But no one was interested.

Charles decided to work on his own, living off their savings, and write a book that would prove the value of his idea and convince the world to pay attention. For three years he worked feverishly, the words spilling out in such a torrent that he began typing directly onto wax stencils for printing—no editing. He finished the book in 1949, just as their money was running out. Claire sent six thousand letters to universities and government institutions all over the world announcing the publication of his fantastic new invention. They waited for the orders to start rolling in.

There was no response. Despite having lived through the horrors of the Nazis and the privations of refugee life in Shanghai, Charles would refer to the time after the publication of Semantography as their years of despair. He got a job as a spot welder in an automobile factory and worked on his symbols by night. His efforts to gain recognition became larger and more desperate. When he heard that a prominent American educator was coming to Sydney on a lecture tour, he went to the airport and managed to push his way into the man’s taxi, where he spent the whole ride to the hotel firing off a sales pitch.

And when the philosopher Bertrand Russell came to town, Bliss somehow managed to wangle an audience with him. These kinds of actions did not endear Bliss to the public officials who sponsored lecture tours, but sometimes they did get him results. Russell wrote him a polite letter of endorsement (which Bliss quoted, or reproduced in full, in everything he ever subsequently published), and Bliss got his name, and his system, into the local papers.

He struggled on, giving lectures on Semantography to any organization that would have him, until Claire died of a heart attack in 1961. Charles was devastated. He no longer wanted to go on living. But “after 3 years of desolation,” he regained his “fighting spirit” and started working again, this time to vanquish the bureaucrats and university professors who, in his eyes, had murdered Claire with their apathy. He was also moved to action by the “tourist explosion.” Governmental bodies started looking for ways to standardize and improve symbols on road signs and in airports, and “academic busy-bodies ran to scientific foundations and asked for millions of dollars for research.” But they never mentioned Bliss’s work in their papers. So Charles changed the name of his system to Blissymbolics, so the “would-be plagiarists could not take over.”

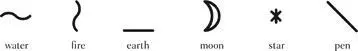

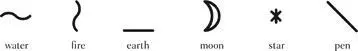

Blissymbolics was in some ways a throwback to the seventeenth-century philosophical languages. Bliss broke down the world into essential elements of meaning and derived all other concepts through combination. But his symbols got their meaning not by referring back to a conceptual catalog (à la Wilkins) or a stanza and line of a memorized verse (à la Dalgarno) but by presenting a picture. Here are some of his basic symbol elements:

Bliss conveys more complex notions in a less direct manner—rain is not a drawing of rain, but a combination of “water” and “down”:

The basic symbol for water occurs in the symbols for all kinds of concepts having to do with liquid:

The combinations are not strictly pictorial, but there is a connection between the meaning of the symbol and the way it looks. Because of this connection, Bliss claims, “the simple, almost self-explanatory picturegraphs of Semantography can be read in any language.”

However, the further from the world of concrete objects Bliss gets, the more dubious this claim becomes. See if you can determine the meaning of the following combination:

Does it mean “depression,” sad because of negative thoughts? Or maybe something like “forced optimism,” when you feel unhappy and you mentally negate it? Or maybe it’s some kind of bad emotion that happens when you have run out of ideas? Giving up?

According to Bliss’s explanation, the meaning of the combination is “shame,” the feeling you get when you are “ unhappy  because your mind

because your mind  thinks no

thinks no  to what you have done.”

to what you have done.”

Well, sure. That’s one way to create a picturable image for “shame.” But it is not the only way. Another symbol-based language, aUI (the language of space), was developed by John Weilgart in the 1960s, at the same time Bliss was struggling to be heard. His word for “shame” was formed like this:

Читать дальше

because your mind

because your mind  thinks no

thinks no  to what you have done.”

to what you have done.”