In 1959 he went to Poland. “Nobody went to Poland in ′59 except crazy Esperanto people,” he said, “and I traveled all over the place. I was in Iran right before the revolution with Esperantists, and what I heard the Esperantists saying about Iran was nowhere to be found in the newspapers. Here I was in direct contact with a collection of people who were not beholden to the United States or Britain or whatever, and were not going to tell me what they thought I wanted to hear. So I was able in a sense to get a particular notion of the truth that other people didn’t have.”

I mentioned a man I had met at the Havana congress, an Icelandic fisherman who couldn’t be more gaunt, or more silent, or farther from home. He first learned about Esperanto from a radio broadcast, studied it from a book, and had been to every universal congress since—Berlin, Tel Aviv, Zagreb, Fortaleza, Gothenburg. That July, he was headed for Beijing. “You know,” Tonkin said, “there are a lot of Esperantists out there who just haven’t yet found their way to Esperanto.”

Back where it all started for me, at that MIT conference, I never did gain an understanding of the role of rock music in Esperanto culture. But I did get to hear Kimo play. On a stage set up on the lawn in front of the student center on the main quad, he brought out his accordion while his friend Jean-Marc LeClerq, formerly of the group La Rozmariaj Beboj (the Rosemary’s Babies), tuned his guitar. They began with the mellow strains of “Besame mucho”: “Kisu min / Kisu min multe.”

Two gray-haired women in matching green dresses twirled to the music, their feet bare in the grass. A large-bellied man with a big green star on both his cap and his belt buckle stood with his hands in his pockets, swaying awkwardly. Others joined the ladies, or perched on benches and sang along. Outsiders wandered by. The curious ones stopped to listen or to take a leaflet from a friendly college student in an Esperanto T-shirt. Others sniggered or rolled their eyes as they refused the leaflet and continued on. I sat at a careful distance from the stage, hoping it wasn’t too obvious that I was part of this group but feeling guilty for thinking so. While Esperantoland has its share of people you don’t want to meet—insufferable bores, sanctimonious radicals, proselytizers for Christ, communism, or a new kind of vegetarian healing—for the most part, the Esperantists I encountered were genuine, friendly, interested in the world, and respectful of others. Though I may not have fully crossed over myself, I did develop a protective defensiveness about them.

Is it crazy to believe that Esperanto has a chance in the age of English? It’s insane. Ask any businessman in Asia, any hotel operator in Europe. Is it ridiculous to believe that a universal common language will bring peace to the world? Of course it is. We have all the brutal evidence we need: the fact that Serbians and Croatians speak the same language did not prevent the bloodshed in Yugoslavia; the shared language of the Hutus and Tutsis did nothing to stop the massacres in Rwanda. Do Esperantists really believe either of these propositions? Whether they do or they don’t, as far as they are concerned, they’re doing their part. It can’t hurt.

The world may not need Esperanto, but it does need people who, like Zamenhof, are moved to act against the “enmity of nations.” Knowing Zamenhof’s fate makes it difficult to dismiss his life’s work with a chuckle. During the bloody peak of World War I, Zamenhof’s brother Aleksander killed himself upon being ordered into the Russian army because he couldn’t bear to face once again the horrors he had witnessed while serving as an army doctor during the Russo-Japanese War. Not long after that, in the midst of death and destruction on a scale he never could have imagined, Zamenhof’s heart gave out. He was lucky. He would not have to know that his lineage would end in yet another world war with the murder of his children at Treblinka.

Kimo and Jean-Marc began another song whose tune was unfamiliar to me. An original Esperanto song. Normando, a slight man with a hint of gray in his beard, came and sat on the grass across from me, his legs folded under him, facing me with his back to the stage. He proved to be a sweet-natured Esperanto ambassador who had been kindly introducing me to people and explaining special phrases and vocabulary to me in a modest, non-pedantic way. He leaned forward and in French-Canadian-accented Esperanto explained that the song we were hearing was called “Sola.” People closer to the stage began to sing along, and he said it is often played at youth congresses, where it is a sort of anthem. The lyrics tell the story of a young person who feels completely alone, but then goes to an Esperanto congress and feels such friendship and connection to the world that his loneliness leaves him … until he is back in his own nation in his own little room. “This song,” he almost whispered, “is so meaningful for Esperantists. Sometimes, when it’s played at the congresses, you see people crying.”

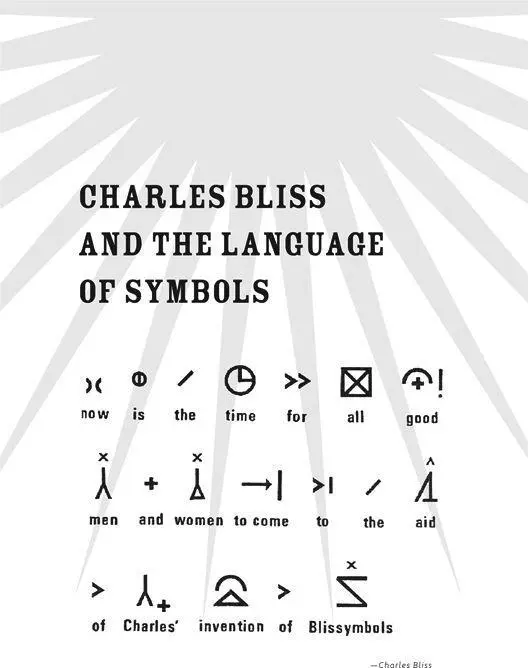

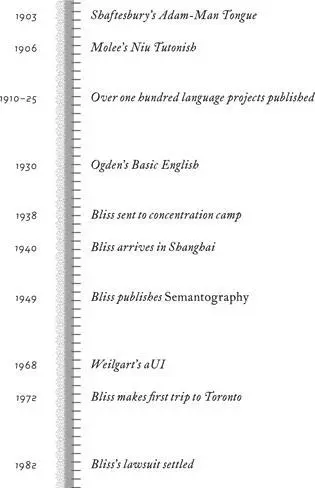

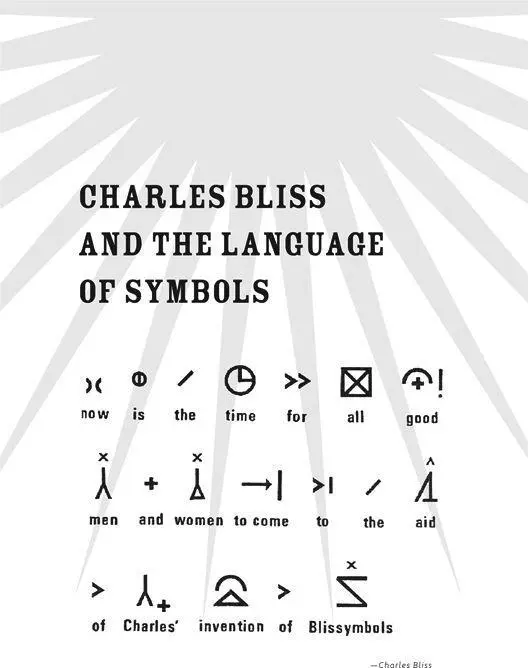

Charles Bliss and the Language of Symbols

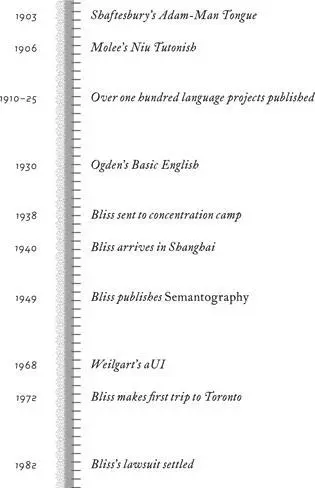

Though Esperanto has survived into the present day, the era of the international language has not. In the years between 1880 and the beginning of World War II, over two hundred languages were published, most of them variations on the same theme: European roots, a set of grammatical endings, no irregularities. The number of projects, and the enthusiasm for them, began falling off in the 1930s, and by the end of the war the era of the international language was over.

There were a few reasons for this. One was the rise of a new lingua franca, on a scale more global than any had been before—English. The era of the international language coincided with the greatest period of growth and consolidation in the British Empire. English was spread to every continent. And Britain’s position at the center of the Industrial Revolution ensured that wealth, status, and power became associated with English. The rising power of the United States during this time added fuel to the English fire, and it soon took over as the primary engine of spread.

In some ways, the noticeable expansion of English was good for the international language movement. The language inventors, looking at the growth of English, saw a threat to their own national languages (most of them were not native English speakers) and worked that much harder to convince the world that a universal neutral language was needed. They found a sympathetic ear. The most active international language supporters were in France and Germany—countries whose languages had the most to lose from the encroachment of English (French was losing its position as the primary language of diplomacy, and German as the primary language of science).

However, in most ways, the advance of English was very bad for the international language movement. The more common reaction was to stick up not for an invented neutral language but for your own home language, as France did in meetings of the League of Nations. Another alternative was to just accept English as the new lingua franca, as Sweden and Norway did in those same meetings. (Denmark wanted Ido.)

By the beginning of the 1920s, English had accumulated a heap of advantages—economic power, political power, large numbers of speakers—but it was not the only potential world language in town. French, Portuguese, Russian, and other colonial languages also enjoyed such advantages (though none on as grand a scale). However, by the end of the 1920s, English had added to its arsenal even more compelling advantages: jazz, radio, Hollywood. It became the language of a new, media-driven popular culture. It was the lingua franca not just of elite pursuits—diplomacy, business, science, belles lettres—but of good ol' entertainment. It swaggered around with a gum-cracking friendly confidence, shaking hands and winning people over.

Читать дальше