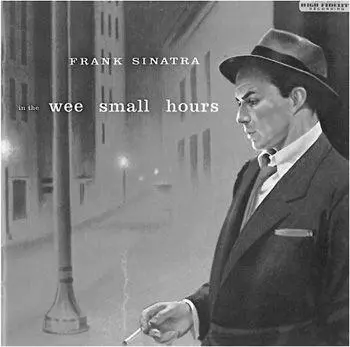

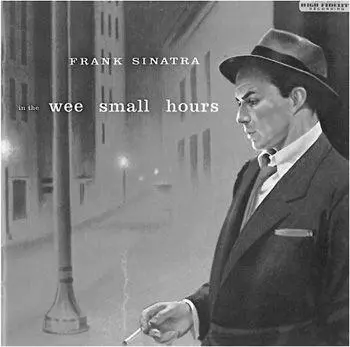

6. The cover of the 1955 record album by Frank Sinatra. The nursery rhyme ‘Wee Willie Winkie’ has done a great deal to popularise the word among non-Scottish children.

Eventually wee became an adjective meaning ‘extremely small’, ‘tiny’. And often it was used in a more general sense: ‘little’. A wee bairn was just a ‘small child’. Then an interesting development took place: wee became a term of endearment — a friendly, welcoming word — and began to lose its association with size. That’s how it’s often used today. If someone in Scotland invites you for a wee drink , beware! It won’t necessarily be a small one.

Scottish English emerged as a really distinctive dialect of the language very early on. It all began when English loyalists fled to Scotland after the Norman Conquest in 1066. They were made welcome there, and by the 13th century English had become the dominant language of the lowland south and east. Then, in 1296, Edward I of England invaded Scotland — the start of a 300-years war. It’s hardly surprising, accordingly, that with Scots identity at stake the English language would soon evolve a local character, quite unlike anything south of the River Tweed.

And it certainly did. Today, Scots English is alive and well, heard and seen in a variety of dialects, and with a local vocabulary of thousands of words, such as gang (‘go’), richt (‘right’), bonnie (‘pretty’) and mickle (‘great’). Some of the words and phrases have travelled well outside Scotland, as wee illustrates. But the prize for the most famous and well-travelled Scots expression has surely got to go to Auld Lang Syne — the Robert Burns poem sung traditionally at New Year. It literally means ‘old long since’ — that is, ‘for old times’ sake’. The words and tune have attracted the singers too, such as Billy Joel and Bobby Darin, and they’ve appeared in dozens of films. Not a bad result, for a British regional dialect.

27. Grammar — a surprising link (14th century)

27. Grammar — a surprising link (14th century)

Grammar is glamorous? For many people, that would be an impossible association of ideas, remembering a time when they were taught English grammar in school, trying to analyse complicated sentences into parts, and learning rules and terms whose purpose was never clear. Glamorous it wasn’t. For others, the association would be pointless, for they were never taught any English grammar at all.

This was a great shame, as grammar, when taught properly, is indeed an exciting and stimulating subject. It’s the study of the way we compose our sentences, of how we say what we mean and of the different effects we convey by varying the order of our words. In short, grammar shows us how we make sense. And the more we know about grammar, the more we understand how language works.

But this book isn’t about grammatical constructions; it’s about words. And when we explore the origins of the word grammar , we find some real surprises. Would you expect an encounter with magic and the supernatural? Read on.

Grammar comes from a Latin word, grammatica , which in turn derives from gramma , meaning a written mark, or letter. It originally included the study of everything that was written — literature as well as language — and eventually this sense was extended to mean the knowledge that a person acquires through literacy. But people who could read and write were an élite. They included not only monks and scholars but also those who dealt in astrology and magic. This is where the supernatural comes in. In medieval Europe, the word grammar was often used to talk about the study of the occult. And when the word arrived in English, in the 14th century, it brought in those associations. A new word emerged: people would talk about gramarye , meaning ‘occult learning’, ‘necromancy’.

It’s this magical sense that leads to glamour . In the 18th century in Scotland, people took up the word grammar , meaning ‘an enchantment’ or ‘a spell’, but they changed the pronunciation. Devils and wizards were said to cast the glamour over the eyes of onlookers. From here it was a short step to the meaning of an alluring charm surrounding someone or something. And in the 20th century, we see the word arriving at its present-day sense of ‘charm’ and ‘attractiveness’. In the 1930s, people talked about glamour boys — a phrase given popular appeal when it was used to describe the handsome young airmen of the wartime RAF. Eventually the adjective came to be used chiefly for women, especially after the movies popularised the phrase glamour girls , and the pin-up photograph became widespread.

The word took an unexpected direction in the 1950s, when it began to be used as a euphemism for nude or topless modelling. If you were offered glamour photographs , you wouldn’t expect to see much clothing. Girls, such as those gracing page 3 in The Sun newspaper, were described as glamour models , and the agencies and events promoting them were said to be on the glamour circuit . The term is still widely used in this way.

The unexpected link between grammar and glamour illustrates a general point about the history of words. Often, a source word develops meanings that are so different from each other that we don’t suspect they have a common origin. Who would ever guess that there’s a common origin for salary , sausage, sauce and salad ? And who would ever have predicted that grammar would one day give birth to such a flamboyant and publicity-seeking child as glamour ? Grammar hasn’t yet achieved such a vivid popular presence — but I live in hope.

28. Valentine — first name into word (14th century)

28. Valentine — first name into word (14th century)

On 14 February each year, in many countries, people send valentines as love tokens — usually a card, flowers or a small gift. Often it’s a chance for one person to express secret admiration for another. People sometimes spend ages deciding what to send and whether they ought to send it. But they probably don’t spend a moment reflecting on the linguistic character of what it is they’re sending.

Valentine is an example of a first name being used as a common noun. The practice is surprisingly common, though many of the uses are specialised or slang. Certain kinds of apples, pears, daisies, magpies and fish have all at some time or other been called Margaret . Certain kinds of flags ( Blue Peter ) and card tricks (in whist or bridge) have been called Peter — as have cash registers, prison cells and penises.

Sometimes the name becomes part of a generally used idiom. People talk about a Jack of all trades , simple Simon , a proper Charlie , taking the Mickey and every Tom, Dick or Harry . In Australian English, Sheila is used colloquially for a young woman and John for a policeman (from French gendarme — ‘johndarm’). John can be a lavatory in American English. Literature provides examples too, such as a Sherlock for a detective or a Lolita for a sexually precocious young girl. And the Bible has given us an Adam for a gardener, a Samson for a strong man and a Solomon for a wise man. Named disasters can travel too: ‘We don’t want to see another (hurricane) Katrina.’

Читать дальше

27. Grammar — a surprising link (14th century)

27. Grammar — a surprising link (14th century) 28. Valentine — first name into word (14th century)

28. Valentine — first name into word (14th century)