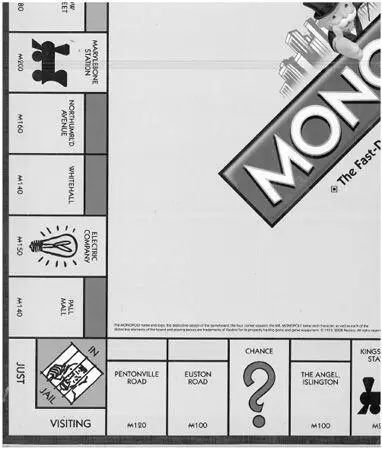

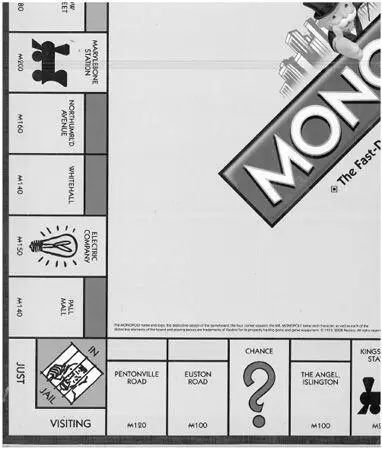

5. In Monopoly, one goes directly to jail, not gaol. Over a hundred local variants of the game have now been licensed. A spin-off dice-game was called ‘Don’t Go To Jail’.

But at least the meaning stayed the same in this instance. In many other cases of ‘double borrowing’, the two words developed different meanings. Today, convey (from Norman French) doesn’t have the same meaning as convoy (from Parisian French). Nor are Norman reward , warden , warrant and wile the same as Parisian regard , guardian , guarantee and guile .

Three hundred and fifty years on, the problem of gaol and jail is still there in British English. The Americans sorted it out in the 18th century, opting for jail , and that’s the only form found in the USA today. But Britain kept both. Official legal documents preferred the gaol spelling. British and Irish prisons were originally spelled Gaol . Oscar Wilde wrote a ‘Ballad of Reading Gaol’. In speech, of course, there’s no difference: both words are pronounced ‘jail’.

Gaol seems to be disappearing from everyday writing nowadays in Britain, though lawyers still use it. And it’s still popular in some other countries, such as Australia. Overall it’s definitely the junior partner: a mere 2 million hits on Google in 2010, compared with 52 million for jail . It’s difficult to say just when the replacement trend started. Some people put it down to the influence of the popular board game Monopoly, invented in the USA. When the game was ‘translated’ into Britain in the 1930s, the non-London squares weren’t changed. That’s why there is a distinctly American-looking policeman on the ‘Go To Jail’ square. And suddenly British players were being sent ‘directly to jail’.

22. Take away — a phrasal verb (13th century)

22. Take away — a phrasal verb (13th century)

It must have come as quite a shock to Samuel Johnson, slowly working his way through the alphabet for his Dictionary of the English Language in the early 1750s, when he reached the letter T. The end of his great project was in sight, and then he encountered the verb take , with its remarkable number of senses. He had had to deal with complicated verbs before: come had ended up with 56 senses, go had 68 and put had 80. But take was going to require an unprecedented 124.

The high total was caused by a large number of combined forms, where take was used along with another word, such as in , off , up and out , or two words, as seen in take up with . These are called phrasal verbs in modern grammatical parlance. The combination of words expresses new senses. Take off , for example, has such meanings as ‘become airborne’, ‘be successful’ and ‘remove’. Aircraft and projects can take off. Clothes can be taken off.

Phrasal verbs became an important feature of English vocabulary during the Middle Ages. Take away is first recorded around 1300 in its general sense of ‘remove’ or ‘withdraw’, and it soon developed special applications. If someone was taken away , it could mean he died or was killed. If servants were taking away , they were clearing the table after a meal. If something took away from an achievement, it detracted from it. And other senses have arrived in modern times. Since the 1930s, we have had the option of eating food in the place where it has been prepared or taking it away to eat elsewhere.

A few phrasal verbs take on a second life as nouns. If I hand something out , what I deliver is a handout . If I tell someone to go ahead , I give them a go-ahead . And this has happened to take away too. In Britain, the shop that sells food that can be eaten off the premises is called a takeaway (often hyphenated, as take-away ), usually with a characterising adjective: a Chinese takeaway , an Indian takeaway . The word can be used as an adjective too: a takeaway curry , takeaway hamburgers . And since the 1970s it has been applied to the meal itself: We’re having a takeaway tonight . But takeaway isn’t universal in the English-speaking world. In Malaysian and Singaporean English, they use a Chinese word — tapau , food. And American English has opted for different phrasal verbs — take-outs or carryouts .

23. Cuckoo — a sound-symbolic word (13th century)

23. Cuckoo — a sound-symbolic word (13th century)

Most words don’t resemble the things they refer to. There’s nothing about the shape of the word table that shows us an object with four legs and a flat surface. And there’s nothing in the sound of the word commotion that makes us hear a violent disturbance. But English has quite a few words where the opposite is the case: cough, knock, murmur, zoom, crunch, bang, clatter, teeny, babble, splash, plop … The sound of the word seems to imitate the reality to which it refers. Such words are often called onomatopoeic — a term from Greek meaning ‘word creation’ — especially when people are talking about the effects heard in poetry. Linguists call them instances of sound symbolism .

Cuckoo is an excellent example of a sound-symbolic word. In many languages the name of this bird echoes the sound of its call. The effect can’t be heard so well in the Old English word for a cuckoo, geac ; but in the Middle Ages it comes across clearly in the form cuccu . The earliest recorded use, from the mid-13th century, is in the famous ‘Cuckoo Song’, the earliest known singing ‘round’ in English:

Sumer is icumen in, Lhude sing cuccu

The translation is ‘Spring has come in. Loudly sing, cuckoo!’ In Middle English, there was no separate word for springtime; spring as the name of a season isn’t recorded until the 16th century. The word summer was used for the entire period between the vernal and autumnal equinoxes.

But even sound-symbolic words can change their meaning and lose their original echoic associations. This has happened to cuckoo . In the 16th century we see it being applied to people. The bird has a monotonous call and lays its eggs in the nests of other birds, so anyone engaged in unimaginative repetitious behaviour or doing something perceived to be stupid came to be labelled a cuckoo . When Aristophanes’ Birds was translated in the 19th century, the name of the realm built by the birds to separate the gods from mankind was called Cloudcuckooland , and this was then applied to any impossibly fanciful world. ‘You’re living in cloudcuckooland,’ we might say. Later the expression was also used in a shortened form: cuckoo land . And in the 20th century, American English took this direction further: anyone who was thought to be crazy or making an absurd suggestion was, quite simply, cuckoo . And if you were thought to be seriously crazy, you might end up as Jack Nicholson did in the 1975 film, in a cuckoo’s nest .

24. Cunt — a taboo word (13th century)

24. Cunt — a taboo word (13th century)

Taboo words are an important element in every language — not because of their number, but because of their notoriety. No other words attract such public emotions, headlines and legislation. But if a word-book is trying to represent all aspects of a language’s lexicon, they have to be included. And they always provide a fascinating story, even if it is one which some readers may find uncomfortable in the telling.

Читать дальше

22. Take away — a phrasal verb (13th century)

22. Take away — a phrasal verb (13th century) 23. Cuckoo — a sound-symbolic word (13th century)

23. Cuckoo — a sound-symbolic word (13th century) 24. Cunt — a taboo word (13th century)

24. Cunt — a taboo word (13th century)