In 1964, Dwight ‘Wayne’ Batteau was funded by the US Navy to develop a man/dolphin communicator. He described the project as ‘a program of research intended to determine the feasibility of establishing a language, approaching English, between man and dolphin’. An electronic device called a transphonometer was designed to convert the vowels and consonants of humans into whistles. These sounds were transmitted underwater, and the dolphins reproduced the whistles. Specially trained Navy personnel were able to learn this whistle language and communicate with trained dolphins.

Batteau drowned in 1967 before the project was completed, and since then most of the information about the Navy’s work with dolphins has been classified. However, we know that dolphins have been trained to attach explosives and listening devices to enemy ships and submarines. And in the Gulf wars dolphins were used to search the seabed for mines. The man/dolphin communicator may have enabled humans to issue commands to dolphins, but there is no evidence that this is more than say a sheepdog’s ability to learn and respond to the commands of its master. Batteau’s dolphins didn’t talk back — in whistles or otherwise.

Researcher John C. Lilly tried to teach dolphins to talk like humans and claimed in the 1960s that he had trained them to replicate the alphabet. Recordings made at his research centre in the Virgin Islands do have a few examples of dolphins apparently echoing human sounds in high-pitched squeaks, but there was no evidence of dolphins actually uttering human words.

Since then, dolphin-language research studies have concentrated on proving that dolphins can understand and interpret human language rather than replicate it, which is a lot more sensible, as the dolphin’s anatomy is not suitable for making human sounds.

In the 1980s, a female bottlenose dolphin was the subject of Louis Herman’s animal-language studies at the Kewalo Basin Marine Mammal Laboratory in Hawaii. Researchers used a sign language which allowed them to give the dolphins highly complex instructions. For example, ‘left basket right ball’ asks the dolphin to put the ball on her right into the basket on her left. But ‘right basket left ball’ means the opposite — put the ball on the left into the basket on the right. The results were published in 1984 in the human psychology journal Cognition . ‘The dolphins were able to account for both the meaning of words and how word order affects the meaning,’ said Herman.

So far the dream of dialogue between man and dolphins remains just that. Dolphins clearly have a complex sound system, but we’re a long way off from interpreting the meaning of their clicks and whistles. Never mind conversing with them, we still don’t know what they’re saying to each other. Is it ontological discussions on the future of the planet or simply ‘Let’s go get some salmon to eat’? As one language expert comments, ‘Their capacity for communication could range from the level of a dog barking all the way to possible talking.’

The most impressive interspecies language experiments have been with primates, our closest relatives. Noam Chomsky and his followers argue that the ability for language developed in humans after the evolutionary split between humans and primates. They point to the ease with which children acquire language. Children, they insist, have an innate propensity for language which primates simply do not possess. According to Chomsky, it was ‘about as likely that an ape will prove to have a language ability as there is an island somewhere with flightless birds waiting for humans to teach them to fly’.

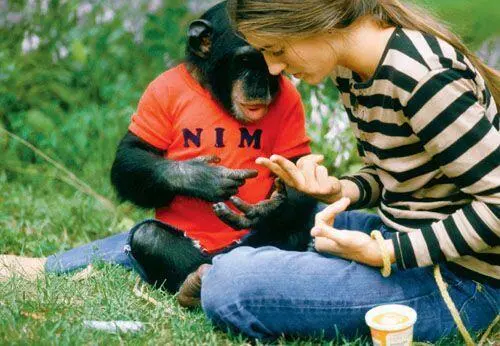

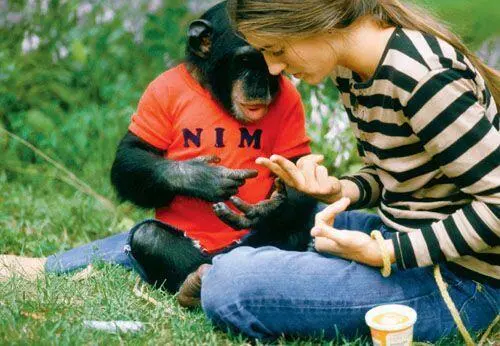

In the 1970s Herbert Terrace, a psychologist at Columbia University, brought a baby chimp (playfully named Nim Chimpsky after the famous linguist) to the LaFarge family in New York. Nim was treated just like one of the family. He had seven human siblings and he was carried everywhere for the first year by his surrogate mother, Stephanie LaFarge. He ate human food, wore nappies and clothes, brushed his teeth at night and — somewhat unusually for a child — enjoyed a cigarette and a cup of coffee. Nim was taught American sign language at home and in a classroom built specially at Colombia.

As Nim hit the terrible twos he became too difficult for the LaFarges to look after. He was moved to a mansion owned by the university and was cared for by a series of handlers. After four years, Terrace announced that Nim had a vocabulary of more than 100 words, but in 1977, after the chimp severely bit one of his teachers, Project Nim was stopped. When the results of the project were published, Terrace declared it a failure. He said that, while he was watching a video of Nim signing with a teacher, he realized that the chimp was imitating most of the signs but he almost never made a sign spontaneously. Herbert had tried to avoid the Clever Hans Effect but in the end he concluded that Nim and other chimps who had been taught to sign were merely imitating rather than using language. Compared with a human child, Nim rarely added new word combinations and seemed to have no idea of syntax or the elementary rules of grammar. Chomsky, it seemed, had been right. Nim would never use language in the way humans do — using grammar to form sentences and express ideas. He never asked a question.

Nim Chimpsky and researcher both signing ‘drink’

After the collapse of the project, no one quite knew what to do with Nim, this chimp who had been raised to believe he was a boy. He’d never been in a cage before or met other chimpanzees. There was a public outcry after he was sold to a laboratory of experimental medicine. Nim’s surrogate sister Jenny Lee told a reporter: ‘How do you reconcile a tiny chimp in blue blankets, drinking from a bottle and wearing Pampers … and then, when he is ten — him in a lab, in a cage, with nothing soft, nothing warm, with no people? This is my brother. This is somebody I raised.’

Nim was eventually offered a home in an animal sanctuary in Texas, where he spent hours looking through old magazines and trying to sign to keepers. Other chimps were introduced as companions, but Nim always relished human companionship. He died of a heart attack in March 2000, aged twenty-six.

The latest celebrity ‘talking’ primate is Kanzi, a bonobo chimpanzee who has been taught to ‘speak’ by pointing at lexigram symbols on a computer. On his keyboard are hundreds of colourful symbols representing all the words that he knows. Not just easy words like ball and banana and tickle but difficult concept words like later and from . When he touches the symbol the word is repeated out loud. What excites primatologist Dr Sue Savage-Rumbaugh at Iowa’s Great Ape Trust is that Kanzi is putting two-word sentences together. For instance, the word ‘flood’ isn’t on the lexigram, so when there was a flood in Iowa, Kanzi pointed out two words big and water . He was given kale to eat and, finding it difficult to chew, he pointed at slow and lettuce .

Kanzi also seems to have developed theory of mind, a skill closely linked to human language. It means he is able to imagine the world from another person’s point of view. When he noticed one of the researchers had a missing finger, he asked ‘hurt?’ And he uses language creatively. Kanzi was told that a Swedish scientist called Pår Segerdahl was coming to visit and was bringing him some bread. There was no symbol on the lexigram for scientist so Kanzi pointed to the symbols for bread and pear . When he was asked if he was talking about Pår or pears to eat, he pointed to the scientist.

Читать дальше