Studies on bilinguals have tried to find out if their view of the world is different, depending on which language they use. Russian-English bilinguals were asked to explain how the world works. When they spoke in Russian they expressed much more collectivist ideas and when they spoke English they spouted more individualistic values. Another study of Japanese women living in the United States asked them to complete sentences in Japanese and then in English, The first sentence was ‘When my wishes conflict with my family’s …’ The Japanese response was ‘it is a time of great unhappiness’. The English was ‘I do what I want’. Another sentence, ‘Real friends should …’ was completed in Japanese with ‘help each other’. In English it was ‘be very frank’.

Languages around the world reflect different understandings of time and space. For example, in English, we use prepositions to express our idea of the past ‘behind’ us and the future ‘ahead’. But some Aboriginal tribes use compass points rather than prepositions to describe both place and time. So time for them moves east to west, not forwards or backwards.

Professor Lera Boroditsky is a psycholinguist at California’s Stanford University. She explains that in many languages there are words like left and right that are used to divide up space. ‘In English we tend to divide our space relative to our bodies,’ she says. ‘If I turn through 180 degrees, the chair that was on my left is now on my right. In some languages words like left and right aren’t used at all, and instead everything is expressed in some kind of geographical system. Sometimes it’s north, south, east, west; sometimes it’s relative to a hill that you live on, or a river that runs through your land. So everything will be up river, down river or across the river. In order to speak a language like that you have to stay oriented with respect to the landscape. You have to be able to say things like there’s an ant on your south-west leg, but if you turn 180 degrees then it will be your north-east leg. So it’s not on your body, it’s really on the landscape.’

But does all this mean that it’s the language which is shaping thought and perception, determining the way we perceive the world, or is it merely pragmatic? After all, it makes sense for a nomadic people to orientate themselves to their environment through compass points because they travel huge distances using landmarks. So what we do is shape our language to our environment — a bit like putting on a suit of clothes which we can adapt depending on the weather, occasion, environment, mood. You can tie yourself in knots over this debate — as many have done.

The question is, has the language developed the way it has because the culture has demanded that of the language? It’s very hard to know which is the chicken and which is the egg. Here’s Professor Boroditsky on the subject. ‘Chicken and egg isn’t the right way to think about it, because humans develop languages as tools for communicating and also as tools for thinking. And we develop the tools that we need, that we want, that we desire in our environment, to achieve the goals that we have. But then the tools that we create also give us cognitive abilities and allow us to do more. That’s why we created them. And so the next generation of speakers really benefits from having those tools built into the language. And these forces mutually influence and reinforce each other.’

What is clear is that languages have always been evolving, often at remarkable speed, and when you look at where our own language, English, came from, you can see just how far it has travelled. And for that historical perspective we have to thank the detective work of two remarkable brothers.

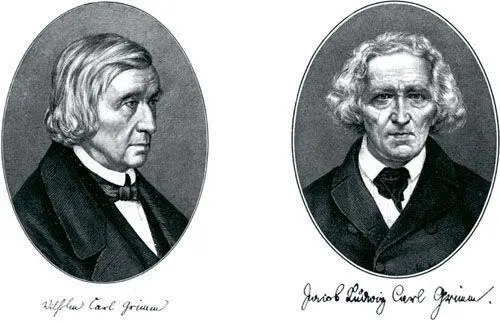

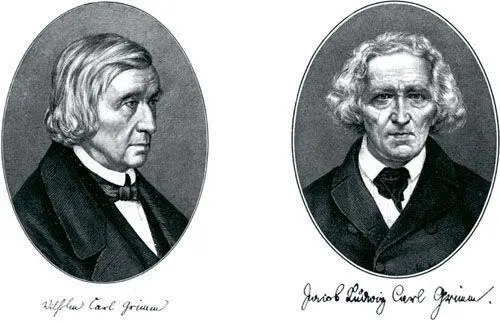

The two brothers were both German professors, and their research into the relationship between similar words of different languages was an important contribution to the study of how language develops. But we know them better as story collectors, the purveyors of tales of wicked stepmothers and frog princes and sleeping princesses that permeate all of our childhoods. They were, of course, the Brothers Grimm.

The tale of this inseparable pair is a compelling one. Two brothers, just a year apart in age, who lived, studied and wrote together for almost their entire lives. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were born in the German town of Hanau, near Frankfurt, towards the end of the eighteenth century. They were the oldest surviving sons in a family of nine children — eight boys and one girl, three of whom died in infancy. Their father Philip was a lawyer and court official, and their early childhood seems to have been happy. Then, when Jacob was eleven, their father died. The family was forced to move from the countryside into a cramped townhouse, and the two boys were sent away to a school in the north. Jacob and Wilhelm went on to study law at university but after their mother died they both took positions as librarians to support their younger brothers and sister.

Both young men were passionate about German folklore and set out on a mission to preserve Germany’s oral tradition and investigate how words change their sounds over time. As part of their research they collected fairy and folk tales from friends and guests, who often recounted stories told to them by their servants; from local peasants and villagers; and from published works from other languages and cultures. The story of Red Riding Hood is thought to have been recounted by Dortchen, a pharmacist’s daughter and childhood friend whom Wilhelm later married.

They published their first collection of eighty-six German fairy stories, Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Tales of Children and the Home), in 1812. The volume included such classics as ‘Cinderella’, ‘Snow White’, ‘Hansel and Gretel’ and ‘The Frog Prince’. The brothers clearly didn’t intend the tales to be read by children or non-scholars. The first edition had a long introduction, reams of notes and no illustrations, and the stories themselves were certainly not child-friendly. These were earthy tales, full of cruelty and hunger and loss, of witches and trolls and ravaging wolves prowling through dark forests. Mothers, not just stepmothers, were evil; a wicked queen was forced to dance in red-hot shoes until she died; a servant was put into a nail-studded barrel and a witch baked alive; children were abducted by a pipe-playing rat catcher; even the Frog King was thrown against a wall to wake him up instead of being kissed. Not Walt Disney, then.

Wilhelm Carl Grimm and Jacob Ludwig Carl Grimm, noted for their work in linguistics as well as their famous fairy tales

The brothers’ different personalities complemented each other. Bachelor Jacob — introverted, physically stronger — was the more academic of the two. He did much of the research for the folklore and the bulk of the work on the theories of language and grammar. Wilhelm was warmer, less physically strong — he had asthma and a weak heart — and he was more interested in literature; he edited and constantly revised the stories to give them their classic narrative style. The brothers continued to collect and publish hundreds of German fairy tales and legends — with limited financial rewards. Fortunately for them, Europe was experiencing a flowering of children’s literature, and illustrated books of folk tales like ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’ were already hugely popular in England. Eventually, after the success of the first English translation of the Grimms’ collection in 1823 ( German Popular Stories , illustrated by George Cruickshank), the brothers selected fifty of their most popular tales, refined and softened many of them and republished the cheaper Kleine Ausgabe (Small Edition) in 1925. Their younger brother, Ludwig, illustrated it.

Читать дальше