Julian : Glinged

Jean : Glinged, very, very good. Very good.

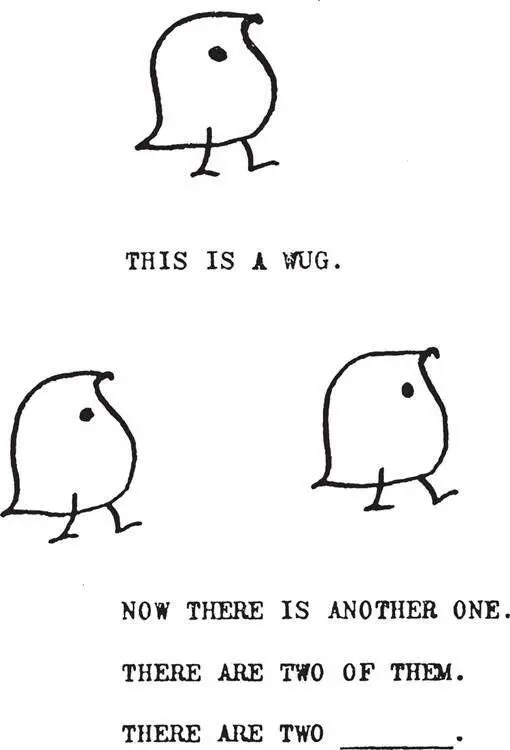

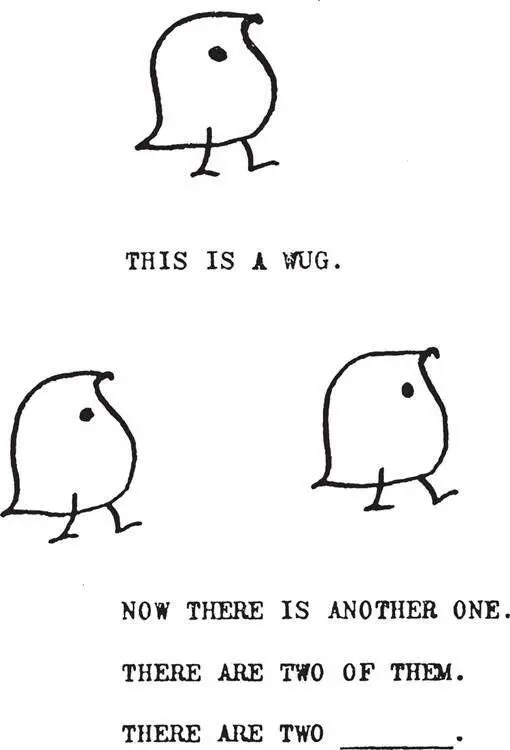

The Wug Test

Jean carries on for half an hour, and it’s clear there’s quite some variation in the children’s ability to form these grammatical structures. She explains that much depends on the individual child’s development; a few months makes a huge difference in a two-, three- or four-year-old.

So what is Jean’s take on the whole nature/nurture debate? She believes that what makes us human beings is our capacity to build our brains. ‘Young kids’ brains are not formed when they’re born, there’s not some organ in them that is grasping language. They have areas that will ultimately be specialized for language but it’s through experience, it’s through hearing language, it’s through interacting with people who use language with you that you build the language in your brain, because you have that capacity.’

If you were to take a healthy newborn baby, nothing wrong with it, physiologically able to hear and speak, and then you were to shut the baby away from all human contact, what language would the baby speak when it uttered its first word? Would it be that putative language that Adam and Eve spoke before the Tower of Babel and the unleashing of thousands of languages? Or gibberish? Or would it speak at all?

At various times in history, experiments have been carried out to isolate children from society, with the express desire of finding this original language. The idea horrifies us now, but in times of despotism and a somewhat laissez-faire approach to human rights, such experiments were possible. The Greek historian Herodotus wrote about Psammetichus I, ruler of Egypt in the seventh century BC. The pharaoh wanted to settle the question of who were the oldest people of mankind, so he gave two newborn babies to a shepherd and ordered him never to speak to them. The hope was that the first word either of the children uttered would be in the root language of all people. One day the children held their hands out to the shepherd and cried ‘bekos ’ . The pharaoh was informed that bekos was what the people of Phrygia — modern-day Turkey — called bread and so he decided that the Phrygians were the oldest people in the world.

A monk in the thirteenth century recorded a language experiment of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in which all the infants appear to have died. According to the Cronica of Franciscan friar Salimbene di Adam, the emperor bade

foster-mothers and nurses to suckle and bathe and wash the children, but in no ways to prattle or speak with them; for he would have learnt whether they would speak the Hebrew language … or Greek or Latin or Arabic, or perchance the tongue of their parents of whom they had been born. But he laboured in vain, for the children could not live without clappings of the hands, and gestures and gladness of countenance, and blandishments.

Scotland’s scientifically curious monarch James IV conducted a similar experiment in 1493. According to the historian Robert Lyndsay of Pitscottie, King James sent two infants to be raised by a deaf and dumb woman in a cabin on Inchkeith Island in the middle of the Firth of Forth. James too was searching for the original language of man. There’s not much information on the results of the experiment. ‘Some say they spoke good Hebrew,’ reported Lyndsay; ‘for my part I know not, but from report.’ The novelist Sir Walter Scott took a more sceptical view when he recounted the tale 300 years later. ‘It is more likely they would scream like their dumb nurse, or bleat like the goats and sheep on the island.’

It’s unclear what the Mughal emperor Akbar the Great was up to with his language-deprivation experiments in the sixteenth century. Some say he wanted to find out whether people were innately Hindu, Muslim or Christian. Others that he was testing his hunch that babies raised without hearing speech would be unable to speak. He ordered twelve infants to be raised by mute nurses in a house where no speech was ever heard. Several years later, when he visited the children, he found his second hypothesis to be correct. None of them could speak; they communicated instead in signs.

Akbar the Great experimented on children with language deprivation

There are probably a few tall tales mixed in with the accounts of these horribly cruel experiments, but generally the results were inconclusive and irrelevant. Clearly there was no ‘original’ language which infants deprived of speech would speak; they simply didn’t speak at all. Stories about feral children, where language has been deprived by chance rather than by the order of a king, are better documented. A feral child is defined as a human child who has lived away from human contact from a very young age and has had little or no experience of human care, loving or social behaviour and, crucially, of human language. Studies of such children can help to understand the process of how language is acquired — how much of it is learned and how much is genetic. Unfortunately, in almost all the studies of feral children, practically nothing is known about the child’s life before their capture.

One of the most famous and well-documented cases is the so-called Wild Boy of the Aveyron. In 1797, in the midst of the madness of the French Revolution, a boy (aged about eleven or twelve) was discovered wandering in the forests of France’s south-eastern Massif Central, one of the most rugged and least inhabited regions of Europe. A hunter came upon the lad living alone, without clothes, without tools, eating and defecating like an animal and, most significantly, without language. He was captured and brought to Paris, where crowds thronged to see him. Victor, as the wild boy became known, offered France an opportunity to see the romantic theories of Jean-Jacques Rousseau in practice. Rousseau’s famous treatise posited the development of a child away from the influences of society, so that he could grow up as Nature intended. What the sightseers found in reality was a dirty, grunting creature, rocking backwards and forwards like an animal in a zoo.

Victor ended up under the care of a young doctor, Dr Jean-Marc Itard, at the recently established Institute for Deaf Mutes in Paris, which had been founded by the celebrated inventor of sign language Abbé Charles-Michel de l’Epée. Itard was a child of the Enlightenment and was fascinated by Locke’s theory that we are born with empty heads and that our ideas arise from what we perceive and experience. Itard decided he would need to educate Victor from the very beginning and so became his Pygmalion. Over the next five years he devoted himself to the boy, teaching him how to eat, use a toilet, repress his animal urges (particularly with the female inmates) and learn French. Victor’s vocal chords, like any muscle unused for so long, needed to be exercised, and Victor gradually began to articulate sounds, rather in the manner of a baby. It became clear he was not a deaf mute, although he may have suffered to some degree from autism which may have been the reason he had been abandoned in the first place. Itard’s methodology is what we would now consider behaviour modification — a system of punishment and rewards; with this treatment he hoped to prove one of the tenets of the French Revolution, namely that nurture could modify nature. At the end of five years Victor had learned some basic signs but, critically, he never learned to speak. Itard gave up, and Victor, after his brief moment of celebrity, lived in anonymity with Itard’s housekeeper until his death in Paris in 1828.

Читать дальше