Musk’s longtime interest in solar power and in finding other new ways to harness energy expanded at Penn. In December 1994, he had to come up with a business plan for one of his classes and ended up writing a paper titled “The Importance of Being Solar.” The document started with a bit of Musk’s wry sense of humor. At the top of the page, he wrote: “The sun will come out tomorrow….”—Little Orphan Annie on the subject of renewable energy. The paper went on to predict a rise in solar power technology based on materials improvements and the construction of large-scale solar plants. Musk delved deeply into how solar cells work and the various compounds that can make them more efficient. He concluded the paper with a drawing of the “power station of the future.” It depicted a pair of giant solar arrays in space—each four kilometers in width—sending their juice down to Earth via microwave beams to a receiving antenna with a seven-kilometer diameter. Musk received a 98 on what his professor deemed a “very interesting and well written paper.”

A second paper talked about taking research documents and books and electronically scanning them, performing optical character recognition, and putting all of the information in a single database—much like a mix between today’s Google Books and Google Scholar. And a third paper dwelled on another of Musk’s favorite topics—ultracapacitors. In the forty-four-page document, Musk is plainly jubilant over the idea of a new form of energy storage that would suit his future pursuits with cars, planes, and rockets. Pointing to the latest research coming out of a lab in Silicon Valley, he wrote: “The end result represents the first new means of storing significant amounts of electrical energy since the development of the battery and fuel cell. Furthermore, because the Ultracapacitor retains the basic properties of a capacitor, it can deliver its energy over one hundred times faster than a battery of equivalent weight, and be recharged just as quickly.” Musk received a 97 for this effort and praise for “a very thorough analysis” with “excellent financials!”

The remarks from the professor were spot-on. Musk’s clear, concise writing is the work of a logician, moving from one point to the next with precision. What truly stood out, though, was Musk’s ability to master difficult physics concepts in the midst of actual business plans. Even then, he showed an unusual knack for being able to perceive a path from a scientific advance to a for-profit enterprise.

As Musk began to think more seriously about what he would do after college, he briefly considered getting into the videogame business. He’d been obsessed with video games since his childhood and had held a gaming internship. But he came to see them as not quite grand enough a pursuit. “I really like computer games, but then if I made really great computer games, how much effect would that have on the world,” he said. “It wouldn’t have a big effect. Even though I have an intrinsic love of video games, I couldn’t bring myself to do that as a career.”

In interviews, Musk often makes sure that people know he had some truly big ideas on his mind during this period of his life. As he tells it, he would daydream at Queen’s and Penn and usually end up with the same conclusion: he viewed the Internet, renewable energy, and space as the three areas that would undergo significant change in the years to come and as the markets where he could make a big impact. He vowed to pursue projects in all three. “I told all my ex-girlfriends and my ex-wife about these ideas,” he said. “It probably sounded like super-crazy talk.”

Musk’s insistence on explaining the early origins of his passion for electric cars, solar energy, and rockets can come off as insecure. It feels as if Musk is trying to shape his life story in a forced way. But for Musk, the distinction between stumbling into something and having intent is important. Musk has long wanted the world to know that he’s different from the run-of-the-mill entrepreneur in Silicon Valley. He wasn’t just sniffing out trends, and he wasn’t consumed by the idea of getting rich. He’s been in pursuit of a master plan all along. “I really was thinking about this stuff in college,” he said. “It is not some invented story after the fact. I don’t want to seem like a Johnny-come-lately or that I’m chasing a fad or just being opportunistic. I’m not an investor. I like to make technologies real that I think are important for the future and useful in some sort of way.”

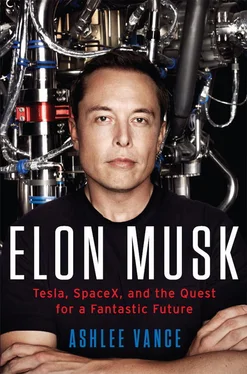

4

ELON’S FIRST START-UP

IN THE SUMMER OF 1994, Musk and his brother, Kimbal, took their first steps toward becoming honest-to-God Americans. They set off on a road trip across the country.

Kimbal had been working as a franchisee for College Pro Painters and done well for himself, running what amounted to a small business. He sold off his part of the franchise and pooled the money with what Musk had on hand to buy a beat-up 1970s BMW 320i. The brothers began their trip near San Francisco in August, as temperatures in California soared. The first part of the drive took them down to Needles, a city in the Mojave Desert. There they experienced the sweaty thrill of 120-degree weather in a car with no air-conditioning and learned to love pit stops at Carl’s Jr. burger joints, where they spent hours recuperating in the cold.

The trip provided plenty of time for your typical twenty-something hijinks and raging capitalist daydreaming. The Web had just started to become accessible to the public thanks to the rise of directory sites like Yahoo! and tools like Netscape’s browser. The brothers were tuned in to the Internet and thought they might like to start a company together doing something on the Web. From California to Colorado, Wyoming, South Dakota, and Illinois, they took turns driving, brainstorming, and talking shit before heading back east to get Musk to school that fall. The best idea to arise from the journey was an online network for doctors. This wasn’t meant to be something as ambitious as electronic health records but more of a system for physicians to exchange information and collaborate. “It seemed like the medical industry was one that could be disrupted,” Kimbal said. “I went to work on a business plan and the sales and marketing side of it later, but it didn’t fly. We didn’t love it.”

Musk had spent the earlier part of that summer in Silicon Valley, holding down a pair of internships. By day, he worked at Pinnacle Research Institute. Based in Los Gatos, Pinnacle was a much-ballyhooed start-up with a team of scientists exploring ways in which ultracapacitors could be used as a revolutionary fuel source in electric and hybrid vehicles. The work also veered—at least conceptually—into more bizarre territory. Musk could talk at length about how ultracapacitors might be used to build laser-based sidearms in the tradition of Star Wars and just about any other futuristic film. The laser guns would release rounds of enormous energy, and then the shooter would replace an ultracapacitor at the base of the gun, much like swapping out a clip of bullets, and start blasting away again. Ultracapacitors also looked promising as the power supplies for missiles. They were more resilient than batteries under the mechanical stresses of a launch and would hold a more consistent charge over long periods of time. Musk fell in love with the work at Pinnacle and began using it as the basis for some of his business plan experiments at Penn and for his industrialist fantasies.

In the evenings, Musk headed to Rocket Science Games, a start-up based in Palo Alto that wanted to create the most advanced video games ever made by moving them off cartridges and onto CDs that could hold more information. The CDs would in theory allow them to bring Hollywood-style storytelling and production quality to the games. A team of budding all-stars who were a mix of engineers and film people was assembled to pull off the work. Tony Fadell, who would later drive much of the development of both the iPod and iPhone at Apple, worked at Rocket Science, as did the guys who developed the QuickTime multimedia software for Apple. They also had people who worked on the original Star Wars effects at Industrial Light & Magic and some who did games at LucasArts Entertainment. Rocket Science gave Musk a flavor for what Silicon Valley had to offer both from a talent and culture perspective. There were people working at the office twenty-four hours a day, and they didn’t think it at all odd that Musk would turn up around 5 P.M. every evening to start his second job. “We brought him in to write some very menial low-level code,” said Peter Barrett, an Australian engineer who helped start the company. “He was completely unflappable. After a short while, I don’t think anyone was giving him any direction, and he ended up making what he wanted to make.”

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу