“On the forty-second day,” Volynov begins, “it was an accident. Electricity switched off. No light, everything stopped, all engines, all pumps. Dark side of orbit. No light from the windows. Weightlessness. We don’t know where is floor or ceiling or maybe it’s a wall. No new oxygen coming. So you may count only on the volume in the station. Nobody from Earth could hear us, and we didn’t have any connection with them. Many problems. Hair like this.” With both hands, Lena mimes pulling her hair out. “What to do? Finally we start to fly over transmitters and we could talk to ground. They told us…” Volynov laughs at the memory. “They told us to open the instruction book to page number such and such. Of course this is of no help. We restored the station with our heads and hands. It took us one hour and half.

“After that, Vitaly couldn’t sleep anymore. He started to have headache, terrible headaches. Stress. We’ve eaten all the medicine. On the ground, they were worried about him. They ordered us to come down.” Volynov says he worked on his own for thirty-six hours without sleep, readying the descent module. It would seem that Zholobov suffered some sort of breakdown.

Later in the afternoon, Lena and I go for a walk through the pines with the psychologist to the cosmonauts, Rostislov Bogdashevsky. He has been at Star City for forty-seven years. Much of what he tells me is abstract and opaque. My notes say things like, “self-organization of dynamic structures of interpersonal relations in human society.” But what he had to say about Volynov and Zholobov was clear and simple. “They were exhausted by overwork. The human organism is built for tension and relaxation, work and sleep. The principle of life is rhythm. Who out of us can work nonstop for seventy-two hours? They made them sick people.”

Neither Volynov nor Bogdashevsky spoke of interpersonal difficulties on board Salyut 5. If anything, the mission seems to have brought the men closer, in the way that disaster and near-death will do. Volynov recalls the rescue helicopter’s approach. “Vitaly heard it first. He tells me: ‘Boris, there are people who are your relatives due to blood connection. But there are also people who are your relatives due to things you do together. Now you are closer to me than your brother or sister. We landed. We are alive. The prize is life.’”

When Volynov hears that Lena and I have been to the Star City museum, he tells us that on a later mission, he returned to Earth in a Soyuz capsule identical to the one on display. “I can still fit,” he says. I try to picture it—Volynov in his business suit, squeezing himself inside the placental confines of a Soyuz seat.

His own capsule, Soyuz 5, isn’t displayed because it was badly damaged. It did not separate properly from the rest of the Soyuz spacecraft, began to tumble, and reentered the atmosphere backward. Volynov, traveling alone, bounced around “like a ping-pong ball.” Only one side of the capsule has a heat-resistant coating, so the outside charred and the inside began to bake. Rubber on the hatch seal was burning. “You could see big balloons because of the heat.”

“Balloons?”

Lena consults Volynov, then turns back to me. “When you bake potatoes in an open fire, you see the same things on the potatoes. Foam? Bubbles.”

“Blisters!”

“ Da, da, da . Blisters.”

Volynov waits for us to finish. “My spaceship looked like these potatoes.” There was a noise like a train, he says. “I thought the floor was opening under my feet, and I had no pressure suit; there is not room for it. And I thought, ‘That’s it. It’s the end.’” If the capsule hadn’t eventually broken free and stabilized in the proper position, Volynov would have been killed.

“When the helicopter arrived, I ask the crew, ‘Is my hair white?’”

To the first space travelers and the men responsible for their survival, mental health was low on the fret list. There was too much else to worry about.

The Hero of the Soviet Union takes a comb from his pocket. He raises his arms and sets them, like a conductor poised to cue the overture. He pulls the comb through the glorious hair (which was not then but is now white), and bends to pick up his groceries. “And now I must run away. People are waiting for me.”

4. YOU GO FIRST

The Alarming Prospect of Life Without Gravity

The world’s first rocket was built by Nazis to deliver bombs without leaving home. For all its fire-breathing bluster, a rocket is simply a means of delivering something—very fast and very far. The rocket was called the V-2. The first payload was the evil sleet of warheads that came down on London and other Allied cities during World War II.

The second was Albert.

Albert was a nine-pound rhesus monkey in a gauze diaper. In 1948, more than a decade before the world had heard of Yuri Gagarin or John Glenn or Ham the astrochimp, Albert became the first living creature to be launched on a rocket to space. As part of the spoils of war, the United States had taken possession of three hundred train carloads of V-2 rocket parts. They were by and large the playthings of generals, but the V-2s caught the imagination of a handful of scientists and dreamers, men more interested in the going-up than the coming-down.

One of them was David Simons. In his oral history, Simons describes a conversation with his boss, James Henry, at the Aeromedical Research Laboratory at Holloman Air Force Base, near White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico. The conversation is classic 1940s, an era when people regularly began their sentences with “Why,…” and “Boy,…”

Dr. Henry starts it off. “Dave, do you think man will ever go to the moon?” I like to picture him in a lab coat, pensively poking his chin with the eraser end of a No. 2 pencil.

Simons replies without hesitating. “Why, of course. It’s just a matter of engineering design and time to work out the problems—”

Henry cuts him off. “Well, what would you think of having an opportunity to help us put a monkey in a captured V-2 rocket that would be exposed to about two minutes of weightlessness and measure the physiological responses to weightlessness?” It was a very long question.

“Oh! What a wonderful opportunity! When do we start?”

It is a moment that, to me anyway, signals the birth of American space exploration. It captures both the geeky excitement and the hand-wringing uncertainty over what might befall a human organism shot to the edges of the known world. Space was an environment in which no one and nothing on Earth had evolved, or, for all the scientists then knew, could survive.

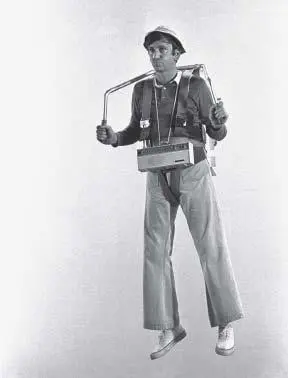

Henry put Simons in charge of Project Albert. I’m looking at a book with photographs from the project. There is the V-2 poised for flight, 50-plus feet tall. There is Albert, with his rhesus monkey muttonchops and delicate eyelids cast down like a doll’s. Below this, a shot of Albert strapped to a tiny stretcher, being slid inside a makeshift aluminum capsule that will fit into the nose cone where warheads were meant to go. You can’t see the face of the enlisted man who holds him, just his midsection: the fly of his khaki pants and the cuff of a too-short shirtsleeve. His nails are dirty. There is his wedding ring. What does his wife think? What does he think? Does it strike him as odd: launching this towering rocket, the world’s first ballistic missile, with nothing on board but a doped-up monkey?

Probably not. Aerospace professionals at the time were gripped with almost universal foreboding at the prospect of cutting loose from gravity’s hold. What if man’s organs depended on gravity to function? What if the pumping of his heart failed to push his blood through his veins, and instead merely churned it in place? What if his eyeballs changed shape and compromised his visual acuity? If he cut himself, would his blood still coagulate? They worried about pneumonia, heart failure, debilitating muscle cramps. Some fretted that without gravity, signals from floating inner-ear bones and other cues to the body’s position would be absent or contradictory—and that this might cause perturbations that would, to quote aerospace medicine pioneers Otto Gauer and Heinz Haber, “deeply affect the autonomic nervous functions and ultimately produce a very severe sensation of succumbence associated with an absolute incapacity to act.” I queried an online dictionary about succumbence . It said, “Did you mean succulents ?”

Читать дальше