5. HARD TO SWALLOW

The Giddy, Revolting Heyday of Ectoplasm

THE LIBRARY AT Cambridge University has its very own admissions office. This is where you are sent should you be so daft as to try to walk in without a Cambridge ID. I’m waiting in the hallway outside, to apply for one-day admittance. Specifically, I’m trying to get into the hallowed Cambridge Manuscripts Reading Room, overseen by the Keeper of Manuscripts and University Archives, whom I picture standing guard at the door in ankle-length robes with a massive key on a chain around his neck. I’m actually nervous about getting in.

While I wait, I read about the sacred texts on exhibit in the lobby. Amongst the many Buddhist works in the Cambridge University Library is this very important Sanskrit palm leaf manuscript, about 1,000 years old…. Cambridge University has one of the most important collections of Buddhist Sanskrit manuscripts in the world .

Meanwhile, yours truly is here for archive item SPR 197.1.6: Alleged Ectoplasm.

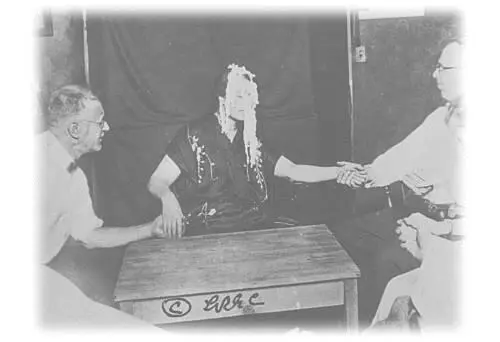

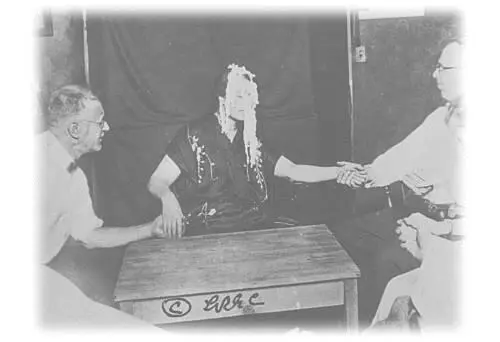

Ectoplasm lived during the table-tipping, spirit-communing, strange-goings-on-in-the-dark heyday of spiritualism. It was claimed to be a physical manifestation of spirit energy, something that certain mediums—called “materializing” mediums—exuded in a state of trance. “This stuff seems to diffuse through the tissues of the [medium] like a gas, and emerges through the orifices because it passes more freely through the mucus membrane than through the skin,” wrote Arthur Findlay, founder of the Arthur Findlay College for mediumship and other spiritualist pursuits. The spiritualists described ectoplasm as a link between life and afterlife, a mixture of matter and ether, physical and yet spiritual, a “swirling, shining substance” that unfortunately photographed very much like cheesecloth.

The original ectoplasmic medium was Eva C., whose emanations drew the attentions of French surgeon and medical researcher Charles Richet. Richet was the discoverer of human thermoregulation and cutaneous transpiration, a pioneer in the treatment of tuberculosis, a recipient of the Nobel Prize for his work on anaphylactic shock, and the author of Gastric Juice in Man and Animals (can’t have a slam dunk every time). That a man of his stature spoke for the authenticity of ectoplasm made it difficult to dismiss. As did spiritualism’s roster of scientists, statesmen, and literary luminaries: William James, William Butler Yeats, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, physicist Sir Oliver Lodge, chemist Sir William Crookes (inventor of the vacuum tube and sufferer of ridicule for his pronouncement that the luminous green gas inside his invention was ectoplasm), two prime ministers, and Queen Victoria.

Spiritualism, in a nutshell, is a religious movement devoted to communicating (via mediums) with those who have died and to proving to others, via séances and other mediumistic demonstrations, that it is possible to do so. Death is viewed not as an end to life, but merely a different phase, a changing of address and scenery. Heaven—or Summerland, as the spiritualists used to call it—was no longer an abstract but a place you could put a call in to. Spiritualism was founded in 1848, by the elder sister of two bored preteens, Margaret and Kate Fox, who took to soliciting mysterious spirit “rappings” at their farmhouse in Hydesville, New York. The noises stirred the imaginations of local townsfolk and the entrepreneurial spirit of their sister, who was soon inviting strangers to the house to observe the proceedings for a modest fee. Within months the three sisters were on a nationwide tour, and spiritualism was off and running. It spread steadily and traveled overseas, peaking in the aftermath of World War I, which left millions of American and European families grieving for lost sons and sadly vulnerable to the promise of contacting them in the afterlife. Though spiritualism’s ranks have dwindled since, it retains a presence in the United States and, more prominently, England.

In 1989, possibly to its great embarrassment, Cambridge University acquired the archives of the Society for Psychical Research, [20] I am an unabashed fan of the SPR (which has been around since 1882) and in particular its quarterly journal. Here are peer-reviewed articles addressing in all seriousness the likes of wart-charming and talking mongooses. Here are time-domain analyses of table rappings and field studies of healers’ effects on lettuce seed germination (“Figure 2: the healer ‘enhances’ the seeds, mimicked by the control healer”). I take it as nothing beyond happy coincidence that the SPR membership roster has at one time or another included a Mrs. H. G. Nutter, a Harry Wack, and a Mrs. Roy Batty.

the preeminent investigators of the early mediums’ claims and feats. Should you wish to view, say, the file labeled “Merton, Mrs.: Investigation of ‘The Flying Armchair’” or “Gramophone Records—Alleged Trance Speech of Banta,” a young, madonna-skinned Manuscripts Room page will find it and place it in front of you with the same reverence and respect he accords items of the Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives or the seed specimens of Sir Charles Darwin.

Unlike the flying armchair, which officers of the SPR swiftly dismissed as hokum, ectoplasm was the subject of elaborate and stone-serious scientific inquiry for more than two decades. Scientific American sponsored an investigation of materializing mediums that was covered in four consecutive issues during 1924. In 1922, the elite Sorbonne University in Paris assigned a team of scientists to sit in on fifteen séances with Eva C., with the specific goal of testing the authenticity of her ectoplasm. (It flunked.) The September 1921 Popular Science Monthly observed that ectoplasm “can assume the shape of a hand or a face or even a whole figure” and is “curiously like human skin in cellular structure.” In 1922, Harvard University graduate student S. F. Damon was featured in the New York Times for his belief that ectoplasm was the elusive “first matter” of the ancient alchemists. The Times index for the years 1920 to 1925 includes more than a dozen entries under “ectoplasm,” ranging from straight-faced coverage of research to more farcical forays, such as “Man Bites a Ghost and Upsets Seance” (“Gallagher actually got a mouthful of ectoplasm….”). Yet you look at any one of the hundreds of photographs of ectoplasm “materializing” from a medium, and it’s clear it was bunk. And not even well-executed bunk. As ghost-biter Gallagher so eloquently put it: “That there stuff is just gauze!” What was going on? What happened to the minds of science that they would, even for a moment, buy into this?

The admissions office lady calls me in and asks for my ID and an “academical letter of introduction.” I hand her a printout of an e-mail from the Keeper of the SPR Archives ( Dear Madam,… The Alleged Ectoplasm is not a pleasant object, I should warn you! ). And that’s it. I’m in.

The reading room is on the third floor. It has ceilings all the way up in heaven and enormous multipane windows with benedictive shafts of light angling down onto the students. The woman across the table is hunched over a notebook, translating and transcribing from an ancient bundle of brittle blue airmail letters penned in Hebrew. The youth to my left is sacrificing his vision and social life to medieval land transfers. A page arrives with my requested materials: six files, a photo album, and a box containing the Alleged Ectoplasm. The box is made of decoratively patterned cardboard and tied up with a piece of string, like something brought home from a pastry shop. It is larger and showier than I expected. I set it on the floor before anyone can ask what’s inside. The plan is to open it later, when my tablemates have left for lunch.

Читать дальше