“Consumerism has a good side and a bad side. The key really is to balance it.” Then she paused. “Are you blaming me?”

“No, our problems today are not the fault of any one person. There was almost no consumer culture when you started. But now, hasn’t it gone too far in the other direction?”

Another pause. “I think you are right. But it is only a small section of society,” she said. “And no matter how horrible you think China is today, you should have seen the China I saw twenty years ago. It was truly like a moonscape, totally different. In some ways, it is better now.” She pauses again. “But it is true that in other ways China is not better: the ungreening of it, the toxins, the plastic things.”

The self-doubt quickly passed. We moved on from climate change and consumer guilt and talked instead about her charity work, about celebrities, about untrustworthy business partners. Her tone was warm. I began to think she might have forgotten the shock. But then, just as I was preparing to leave, she returned midsentence to that unintended, incomprehensible, unforgettable slight.

“I am so unhappy that you didn’t see me last night.”

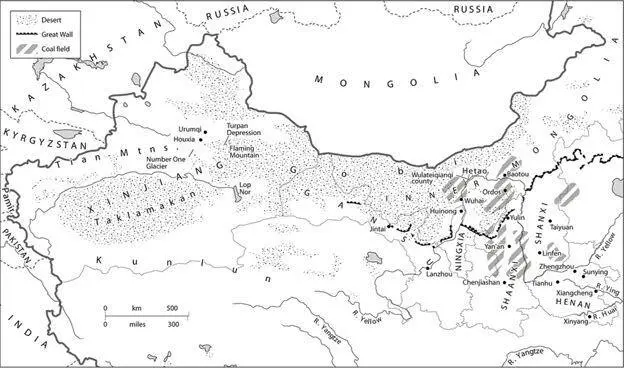

My social climb had hit the ceiling. The worlds of Barbie and the China Doll had converged. In Shanghai, people were under more pressure to look good, to eat expensively, to shop for self-fulfillment. Other cities would follow. The American dream had not yet been realized, but it was drawing closer. Consumption was rising conspicuously, regardless of the fashion for eco-food and green living. On the coast and in Chongqing, I had now seen how trade, industry, urbanization, and other forces of development were all geared toward endless expansion just as in the West. But the planet is a finite space. Something had to give. Where were the stresses being felt? I worked my way next toward the northwest to look at the impact on the land, the water, the air, and the people.

NORTHWEST

Imbalance

9. Why Do So Many People Hate Henan?

Henan

The country is rather over-peopled in proportion to what its stock can employ, and labour is, therefore, so abundant, that no pains are taken to abridge it. The consequence of this is, probably, the greatest production of food that the soil can possibly afford.

—Thomas Malthus on China, 1798 1

China’s most populous 2and, arguably, least popular province lay only an hour by air from the glitz of Shanghai’s consumer culture. Traveling from one to the other could be a jolt in more ways than one. Turbulence is usual on the crowded flight paths over the northern China floodplain, but the flight to Henan was bumpier than usual. The shaking of the fuselage forced the Air China cabin crew, who normally wander up and down regardless of the weather, to strap themselves into their seats. All the passengers were gripping their armrests. For the first time in years I felt anxious about flying. Looking out of the window, we appeared to be descending through dense cloud, but suddenly there was a jolt. For a terrifying second I feared a midair collision. But, no, we were in one piece. What was it? Surely we weren’t down yet. I could see no sign of the ground. But I strained my eyes and, yes, thankfully, there was the runway. A couple of hundred yards away, I could just about make out Zhengzhou Airport terminal. The steel-and-glass building seemed on the verge of disappearing into the filthy haze I had mistaken for a dark nimbus cloud. I relaxed. A degree of grimness was to be expected. After all, this was Henan.

“A vision of the Apocalypse,” “Hell on earth,” “The foulest place in China.” When I mentioned I was to visit Henan, expressions soured, distaste rose, and people I would consider liberal, open-minded, and compassionate spewed forth a stream of derogatory comments. Prejudice had become the norm with regard to this crush of humanity. Well-educated Chinese friends casually dismissed people from Henan as greedy and deceitful. Foreign visitors were barely more forgiving. Those who had never been there knew it as a place of AIDS villages and cancer clusters. Even many migrants from the province said they left because their homes were poor, crowded, and polluted. The antipathy so many Chinese feel toward Henan seems to mirror the prejudice that many foreigners express toward China: that it is dirty, overcrowded, and untrustworthy.

I was there to test a theory that discrimination has its roots in population stress; that excess human pressure on the land hurts the health and well-being of those who live on it.

This idea was at least two hundred years old. In the eighteenth century the notorious doomsayer Thomas Malthus argued that too many people on too little land inevitably resulted in a culling of human numbers. He believed people either regulated themselves or disaster would do the job for them. 3Although he never traveled this far east, the British reverend identified China as the prime example of a population incapable of the self-restraining “preventative checks” that “civilised nations” like Britain were able to apply through religion and education. Instead, he said it was regulated by the “positive checks” of drought, famine, and war. Later Western visitors went so far as to see famine as a necessary evil. 4China’s emperors knew the dangers of imbalance between human demand and environmental supply. The Mandarin word for “population” is made up of two characters, ren (human) and kou (mouth). But Mao, a believer in strength in numbers, preferred to see each person as two extra hands. It is only in the last few decades that Chinese environmentalists have come to see population as a major cause of their nation’s problems. 5Henan illustrates how the attitude to people power has shifted from admiration to concern.

Historically, this province was credited as the cradle of Han civilization. Tai chi, kung fu, and Chan Buddhism (better known outside China as Zen) are said to have originated here. 6It was the birthplace of Lao-tzu and other influential philosophers and was a center of political power in ancient times, boasting three former national capitals: Luoyang, Anyang, and Kaifeng. The province once had dense forests and, according to Mark Elvin, more elephants than Thailand, 7but those beasts have long since been driven away along with the clearance of land for farms, cities, and people. By the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127), Kaifeng was thought to be the most populous city in the world with 2 million people. Frequent famines suggested the capacity of the land and the numbers of dwellers it supported were often out of balance, but as recently as the 1950s Henan was celebrated for clear waters, abundant harvests, and a rich culture.

Since then, the land has come under more human pressure than almost anywhere else in China. The registered population has surged from 42 million in 1949 to over 100 million. Henan’s population is bigger than that of any country in Europe and all but twelve of the world’s nations. 8Yet they are crammed into an area of 167,000 square kilometers—the size of Massachusetts or two Scotlands. This has left the province with the highest rural population density in the country, an environment in tatters, and one of the lowest average incomes. 9Poverty and desperation have made Henan the origin of many of the darkest stories from China: cancer clusters, AIDS villages, slave labor, skewed sex ratios due to selective abortions, birth defects, murder, counterfeiting, and pollution.

Читать дальше