Medieval theologians understood the question, and they appreciated its power. They offered in response the answer that to their way of thinking made intuitive sense: Deus est ubique conservans mumdum. God is everywhere conserving the world.

It is God that makes the electron follow His laws.

Albert Einstein understood the question as well. His deepest intellectual urge, he remarked, was to know whether God had any choice in the creation of the universe. If He did, then the laws of nature are as they are in virtue of His choice. If He did not, then the laws of nature must be necessary, their binding sense of obligation imposed on the cosmos in virtue of their form. The electron thus follows the laws of nature because it cannot do anything else.

It is logic that makes the electron follow its laws.

And Brandon Carter, Leonard Susskind, and Steven Weinberg understand the question as well. Their answer is the Landscape and the Anthropic Principle. There are universes in which the electron continues to follow some law, and those in which it does not. In a Landscape in which anything is possible, nothing is necessary. In a universe in which nothing is necessary, chaos is possible.

It is nothing that makes the electron follow any laws.

Which, then, is it to be: God, logic, or nothing?

This is the question to which all discussions of the Landscape and the Anthropic Principle are tending, and because the same question can be raised with respect to moral thought, it is a question with an immense and disturbing intellectual power.

For scientific atheists, the question answers itself: Better logic than nothing, and better nothing than God. It is a response that serves moral as well as physical thought. Philosophers such as Simon Blackburn, who believe that it is their special responsibility to decline theological appeals, also find themselves forced to choose between logic and nothing.

It is a choice that offers philosophers and physicists little room in which to maneuver. All attempts to see the laws of nature as statements that are true in virtue of their form have been unavailing. The laws of nature, as Isaac Newton foresaw, are not laws of logic, nor are they like the laws of logic. Physicists since Einstein have tried to see in the laws of nature a formal structure that would allow them to say to themselves, “Ah, that is why they are true,” and they have failed. Before determining that he would welcome in the form of the Landscape and the Anthropic Principle ideas that previously he was prepared to reject, Steven Weinberg argued that when at last we are face-to-face with the final theory, we shall discover that it is unique. It is what it is. It cannot be changed. And it is precisely the fact that it cannot be changed that offers the soul surcease from anxiety. In the end, this idea does not serve the cause. If it is impossible to change the structure of a final theory, then uniqueness is simply a coded concept, one standing for necessity itself. And if it is not impossible, the claim that the final laws of nature are unique comes to little more than this: They are what they are, and who on earth knows why?

While better logic than nothing is still on the menu, it is no longer on the table. There remains better nothing than God as the living preference among physicists and moral philosophers. It is a remarkably serviceable philosophy. In moral thought, nothing comes to moral relativism; and philosophers who can see no reason whatsoever that they should accept any very onerous moral constraints have found themselves gratified to discover that there are no such constraints they need accept. The Landscape and the Anthropic Principle represent the accordance of moral relativism in physical thought. They work to cancel the suggestion that the universe—our own, the one we inhabit—is any kind of put-up job. This is their emotional content, the place where they serve prejudice. These ideas have an important role to play in the economy of the sciences, and for this reason, they have been welcomed by the community of scientific atheists with something akin to a cool murmur of relief. They have, for example, worked entirely to Richard Dawkins’s satisfaction. He believes them superior to the obvious theological alternatives on the grounds that it is better to have many worlds than one God.

But before his enthusiasm is dismissed as obviously contrived, it should be remembered that just these principles have led to a startling physical prediction. Using the ideas of the Landscape and the Anthropic Principle, Steven Weinberg predicted that the cosmological constant, as it is observed, should have a small, positive value. In this he was correct. This is very remarkable and it suggests that just possibly these ideas have a depth somewhat at odds with their apparently frivolous character.

I do not know. It does not hurt to say so.

But one possibility in thought should certainly encourage another. If nothing proves unavailing, will physicists accept the inexorable logic of the disjunction God or nothing ?

Writing with what I think is characteristic honesty, Leonard Susskind has this to say:

If, for some unforeseen reason, the landscape turns out to be inconsistent—maybe for mathematical reasons, or because it disagrees with observation—I am pretty sure that physicists will go on searching for natural explanations of the world. But I have to say that if that happens, as things stand now we will be in a very awkward position. Without any explanation of nature’s fine-tunings we will be hard pressed to answer the ID [intelligent design] critics. One might argue that the hope that a mathematically unique solution will emerge is as faith-based as ID.

This remark has an unintended daring. It gives a good deal of ground away. It is generous. And it suggests oddly enough that a conflict in thought that scientists have almost universally dismissed retains a strange, disturbing vitality nonetheless. Do not be misled by phrases such as “faith-based as ID.” It is the word awkward that counts. If the double ideas of the Landscape and the Anthropic Principle do not suffice to answer the question why we live in a universe that seems perfectly designed for human life, a great many men and women will conclude that it is perfectly designed for human life, and they will draw the appropriate consequences from this conjecture.

What is awkward is just that at a moment when the community of scientists had hoped that they had put all that behind them so as to enjoy a universe that was safe, sane, secular, and sanitized, somehow the thing they had been so long avoiding has managed to clamber back into contention as a living possibility in thought.

This is very awkward.

CHAPTER

7

A Curious Proof That God Does Not Exist

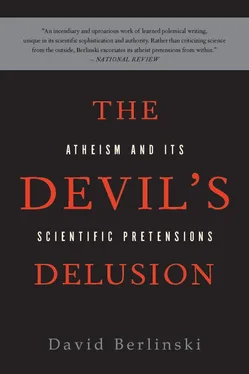

AN ARGUMENT for God’s existence is a commonplace; an argument against his existence is an event. Just such an argument comprises the centerpiece of Richard Dawkins’s The God Delusion. It is an argument to which he attaches the utmost importance: In lectures and talks given since its publication, he has suggested that it now looms very large in the troubled imagination of religious believers. In this he is mistaken. His argument is nonetheless important in another respect. It is an object lesson.

Dawkins summarizes his views in a series of six very general propositions, of which only the first three are directly relevant to his concerns—or mine:

The first affirms that the universe is improbable.

The second acknowledges the temptation to explain the appearance of the universe by an appeal to a designer.

Читать дальше