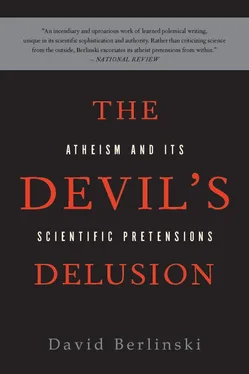

There remains the obvious question: By what standards might we determine that faith in science is reasonable, but that faith in God is not? It may well be that “religious faith,” as the philosopher Robert Todd Carroll has written, “is contrary to the sum of evidence,” but if religious faith is found wanting, it is reasonable to ask for a restatement of the rules by which “the sum of evidence” is computed. Like the Ten Commandments, they are difficult to obey but easy to forget. I have forgotten them already.

Perhaps this is because there are no such rules. The concept of sufficient evidence is infinitely elastic. It depends on context. Taste plays a role, and so does intuition, intellectual sensibility, a kind of feel for the shape of the subject, a desire to be provocative, a sense of responsibility, caution, experience, and much besides. Evidence in the court of public opinion is not evidence in a court of law. A community of Cistercian monks padding peacefully from their garden plots to their chapel would count as evidence matters that no physicist should care to judge. What a physicist counts as evidence is not what a mathematician generally accepts. Evidence in engineering has little to do with evidence in art, and while everyone can agree that it is wrong to go off half-baked, half-cocked, or half-right, what counts as being baked, cocked, or right is simply too variable to suggest a plausible general principle.

When a general principle is advanced, it collapses quickly into absurdity. Thus Sam Harris argues that “to believe that God exists is to believe that I stand in some relation to his existence such that his existence is itself the reason for my belief ” (italics added). This sounds very much as if belief in God could only be justified if God were to call attention conspicuously to Himself, say by a dramatic waggling of the divine fingers.

If this is so, then by parity of reasoning again, one might argue that to believe that neutrinos have mass is to believe that I stand in some relationship to their mass such that their mass is itself the reason for my belief.

Just how are those neutrinos waggling their fingers?

A neutrino by itself cannot function as a reason for my belief. It is a subatomic particle, for heaven’s sake. What I believe is a proposition, and so an abstract entity— that neutrinos have mass. How could a subatomic particle enter into a relationship with the object of my belief? But neither can a neutrino be the cause of my belief. I have, after all, never seen a neutrino: not one of them has never gotten me to believe in it. The neutrino, together with almost everything else, lies at the end of an immense inferential trail, a complicated set of judgments.

Believing as I do that neutrinos have mass—it is one of my oldest and most deeply held convictions—I believe what I do on the basis of the fundamental laws of physics and a congeries of computational schemes, algorithms, specialized programming languages, techniques for numerical integration, huge canned programs, computer graphics, interpolation methods, nifty shortcuts, and the best efforts by mathematicians and physicists to convert the data of various experiments into coherent patterns, artfully revealing symmetries and continuous narratives. The neutrino has nothing to do with it.

Within mathematical physics, there is no concept of the evidence that is divorced from the theories that it is evidence for, because it is the theory that determines what counts as the evidence. What sense could one make of the claim that top quarks exist in the absence of the Standard Model of particle physics? A thirteenth-century cleric unaccountably persuaded of their existence and babbling rapturously of quark confinement would have faced then the question that all religious believers now face: Show me the evidence. Lacking access to the very considerable apparatus needed to test theories in particle physics, it is a demand he could not have met.

In the face of experience, W. K. Clifford’s asseveration must be seen for what it is: a moral principle covering only the most artificial of cases.

The existence of God is not one of them.

Neither the premises nor the conclusions of any scientific theory mention the existence of God. I have checked this carefully. The theories are by themselves unrevealing. If science is to champion atheism, the requisite demonstration must appeal to something in the sciences that is not quite a matter of what they say, what they imply, or what they reveal.

In many respects the word naturalism comes closest to conveying what scientists regard as the spirit of science, the source of its superiority to religious thought. It is commended as an attitude, a general metaphysical position, a universal doctrine—and often all three. Rather like old-fashioned Swedish sunshine-and-seascape nudist documentaries, naturalism is a term that conveys an agreeable suggestion of healthful inevitability. What, after all, could be more natural than being natural? Carl Sagan’s buoyant affirmation that “the universe is everything that is, or was, or will be” is widely understood to have captured the spirit of naturalism, but since the denial of this sentence is a contradiction, the merits of the concept so defined are not immediately obvious. Just who is arguing from the pulpit that everything is not everything?

A triviality having been affirmed, what follows frequently topples over into the badlands in which, like cut asparagus, assertions remain unsupported by argumentative stalks. “Everything,” the philosopher Alexander Byrne has remarked, “is a natural phenomenon.” Quite so. But each of those natural phenomena is, Byrne believes, simply “an aspect of the universe revealed by the natural sciences.” If what is natural has been defined in terms of what the natural sciences reveal, no progress in thought has been recorded. If not, what reason is there to conclude that everything is an “aspect of the universe revealed by the natural sciences”?

There is no reason at all.

If naturalism is a term largely empty of meaning, there is always methodological naturalism. Although naturalism is natural, methodological naturalism is even more natural and is, for that reason, a concept of superior grandeur. Hector Avalos is a professor of religious studies at Iowa State University, and an avowed atheist. He is a member in good standing of the worldwide fraternity of academics who are professionally occupied in sniffing the underwear of their colleagues for signs of ideological deviance. Much occupied in denouncing theories of intelligent design, he has enjoyed zestfully persecuting its advocates. “Methodological naturalism, ” the odious Avalos has written, “the view that natural phenomena can be explained without reference to super natural beings or events, is the foundation of the natural sciences.”

Now a view said to be foundational can hardly be said to be methodological, and if naturalism is the foundation of the natural sciences, then it must be counted a remarkable oddity of thought that neither the word nor the idea that it expresses can be found in any of the great physical theories. Quite the contrary. Isaac Newton in writing the Principia Mathematica seemed curiously concerned to place rational mechanics on a foundation that has nothing to do with methodological naturalism. “The most beautiful system of the sun, planet and comets,” he wrote, “could only proceed from the counsel and domination of an intelligent and powerful Being.”

Читать дальше