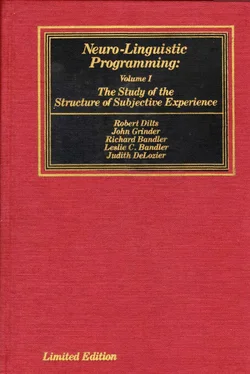

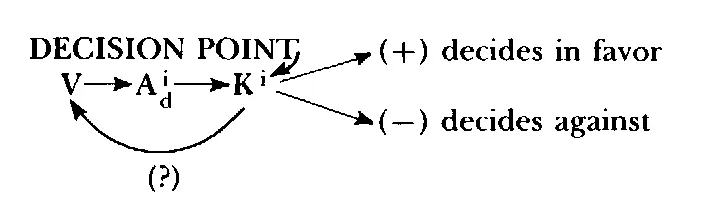

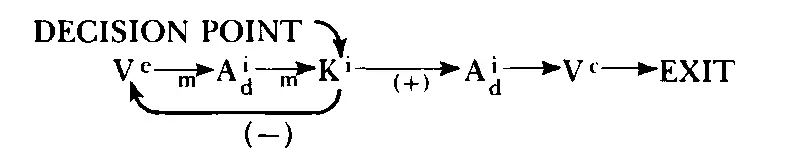

Consider the following diagram of the decision making strategy discussed earlier in this section.

Here, the individual makes a decision by looking at possibilities, describing them to himself and then deriving internal feelings on the basis of those descriptions. The internal feelings constitute the decision point in the strategy. If the feelings are congruently positive (+), the person decides in favor of that particular verbal representation; if the feelings are congruently negative ( —), the individual decides against it. If the feelings are ambivalent or incongruent (?), the individual operates by looking back at the options and by describing them again.

Depending, then, on the outcome you are working toward, you will want to emphasize different kinds of content representations at this step. If it is appropriate for the individual to decide in favor, you will emphasize a positive kinesthetic representation ( + ). If it would be useful for the individual to decide against, you will emphasize negative kinesthetic sensations ( —). If you want many alternatives to be considered, then be sure to stress ambiguity in feelings (?).

Decision points, then, are steps in the strategy where different values of the representational system involved in that step (kinesthetic, visual, auditory or olfactory) will trigger different directions in the unfolding strategy sequence. What happens in the representational system at a decision point will have a great impact on the eventual outcome of the strategy.

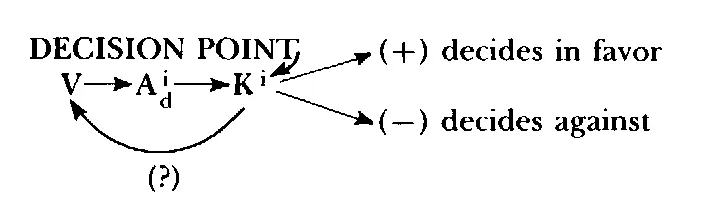

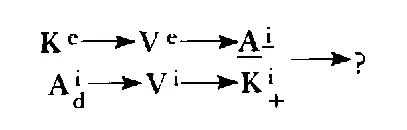

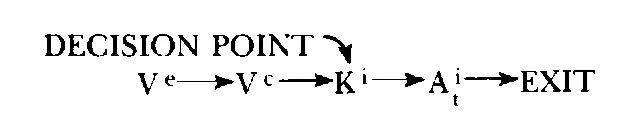

The creative strategy and the motivation strategy that we used for examples in EXERCISES A and B contained two other examples of internal kinesthetic decision points. In the creative strategy:

the internal feelings about the previous verbalizations either trigger an operation in which the subsequent verbalizations are transformed into constructed images, or trigger an operation in which the individual loops back to the beginning of the strategy and looks at the situation again.

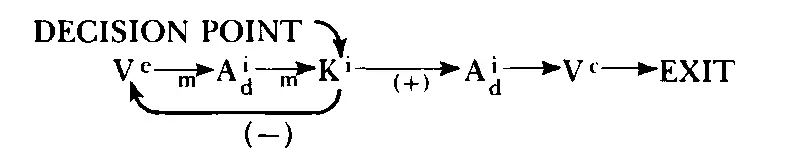

In the example of the motivation strategy:

the internal feelings either initiate the auditory tonal representation and exit to the behavior, or they do not. If the feelings do not initiate the internal tone, no motivation occurs.

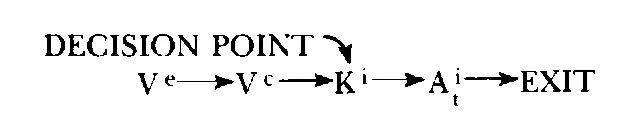

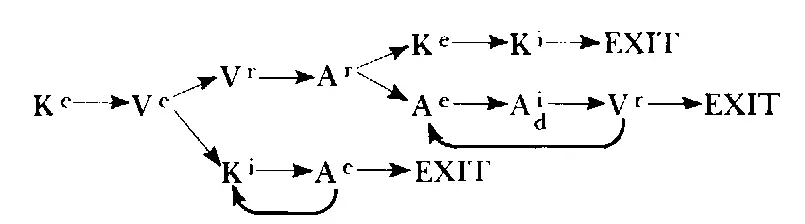

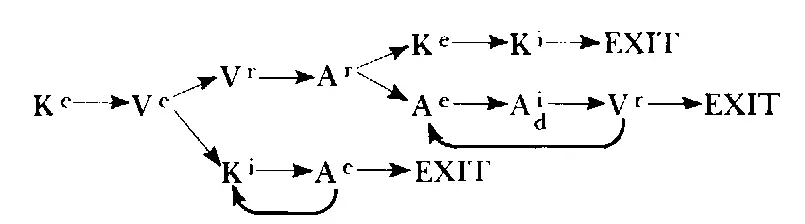

Not all decision points, of course, are internal kinesthetic representations. Consider the following learning strategy:

In this strategy, V eand A rare both decision points. The outcome of this strategy is for an individual to learn or incorporate some behavioral patterns. The person starts off by performing some physical movement or activity (K e). Then, depending on what the external visual feedback (V e) is for that action the person will choose between two subroutines. Within one of these subroutines, some remembered auditory experience will also serve as a decision point where one of two other substrategies will be selected.

Notice also that the V ror A erepresentations that appear at the end of two of the subroutines are also decision points that will either trigger an operation in which the strategy loops back on itself again, or moves on to exit.

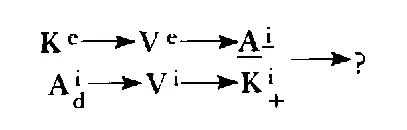

Another example of a decision point would be the situation below:

Here the decision point is shown as a comparison of steps from two different processings of the same content, with conflicting results, A i -and K i +(they feel that they should do one thing, but something tells them to do another). In this situation, most likely, the representational system with the highest signal magnitude will determine what sequence of behavior is to follow.

Your ability to identify and elicit the appropriate representation at the decision point in a strategy will directly determine your success at utilization. In fact, your success at being able to access appropriate decisions at the choice points in a strategy will accurately reflect how well you have paced the individual. Because you are dealing with internal processes it is evident that the more closely you pace the person's strategy the more likely you are to get the representation (and thus the outcome) desired at the decision point.

Successful pacing is irresistible. During our workshops and seminars when we call for a volunteer from the audience to demonstrate a motivation strategy, often several others in the group who happen to share the volunteer's motivation strategy will begin to perform the outcome behavior when we've finished pacing the subject. Or, observers in the audience find that they must consciously restrain themselves from carrying out the behavior because they have become so strongly motivated.

The process of pacing, whether unconscious or deliberate, is undoubtedly at the root of many of the experiences that we label "rapport," "trust," "influence," "persuasion" and so forth. When you pace someone —by communicating from the context of their model of the world — you become synchronized with their own internal processes. It is, in one sense, an explicit means to "second guess" people or to "read their minds," because you know how they will respond to your communications. This kind of synchrony can serve to reduce greatly resistance between you and the people with whom you are communicating. The strongest form of synchrony is the continuous presentation of your communication in sequences which perfectly parallel the unconscious processes of the person you are communicating with — such communication approaches the much desired goal of irresistability.

The phenomena of rapport, trust and influence derive from our ability to observe, understand and use the strategies of those with whom we communicate. Anyone involved in working directly with others (whether parents, businessmen, educators, lawyers, therapists, scientists, government officials, etc.) will know intuitively that a large portion of your successful interactions depend on your ability to establish and maintain rapport. In fact, much of your preliminary encounters with associates each day probably centers around the initial establishment of a certain level of rapport. A knowledge of strategies and the process of pacing will greatly streamline this process for you.

In our other works we describe how the process of pacing can be extended to all aspects of communication. Matching your voice tonality and tempo, vocabulary, posture, gestures, breathing rate and other behaviors to those of the person with whom you are communicating can rapidly and effectively establish rapport with most people (although in particular cases successful pacing can require that you assume a role that is expected of you, one in which your behavior is very different from that of the person with whom you are interacting — doctor/nurse, teacher/student, parent/child, etc.) See Structure of Magic II, Patterns I and II and Changing With Families for further discussion and exercises involving these types of pacing.

Rapport, like many other aspects of neurolinguistic programming, is quite subtle but extremely powerful in its implications and effects. Rapport of some kind is essential to any type of communication. Once you believe rapport has been established through pacing, you should continually test it to make sure you are staying appropriately attuned. The best way to do that is by attempting to "lead" the person. Once you have paced the person you are communicating with and believe you have established a secure rapport, violate your pace and change your behavior — that is, attempt to lead the person you have been pacing into a different behavior. If sufficient rapport and trust have been built up you can make this transition smoothly and easily. If the person doesn't follow you, return to pacing him until you have established the necessary rapport. If the person follows your lead, it will be important that you return to pacing him periodically to keep up rapport. Your leading may be as subtle as a shift in breathing rate, eye gaze, tonality or body posture. Make certain that it is sufficiently overt that you are sure you can observe the change.

Читать дальше