My dream placed me at the centre of Being itself, and there was no escape. It took me months to understand what this meant. During this time, I came to a more complete, personal realization of what the great stories of the past continually insist upon: the centre is occupied by the individual. The centre is marked by the cross, as X marks the spot. Existence at that cross is suffering and transformation—and that fact, above all, needs to be voluntarily accepted. It is possible to transcend slavish adherence to the group and its doctrines and, simultaneously, to avoid the pitfalls of its opposite extreme, nihilism. It is possible, instead, to find sufficient meaning in individual consciousness and experience.

How could the world be freed from the terrible dilemma of conflict, on the one hand, and psychological and social dissolution, on the other? The answer was this: through the elevation and development of the individual, and through the willingness of everyone to shoulder the burden of Being and to take the heroic path. We must each adopt as much responsibility as possible for individual life, society and the world. We must each tell the truth and repair what is in disrepair and break down and recreate what is old and outdated. It is in this manner that we can and must reduce the suffering that poisons the world. It’s asking a lot. It’s asking for everything. But the alternative—the horror of authoritarian belief, the chaos of the collapsed state, the tragic catastrophe of the unbridled natural world, the existential angst and weakness of the purposeless individual—is clearly worse.

I have been thinking and lecturing about such ideas for decades. I have built up a large corpus of stories and concepts pertaining to them. I am not for a moment claiming, however, that I am entirely correct or complete in my thinking. Being is far more complicated than one person can know, and I don’t have the whole story. I’m simply offering the best I can manage.

In any case, the consequence of all that previous research and thinking was the new essays which eventually became this book. My initial idea was to write a short essay on all forty of the answers I had provided to Quora. That proposal was accepted by Penguin Random House Canada. While writing, however, I cut the essay number to twenty-five and then to sixteen and then finally, to the current twelve. I’ve been editing that remainder, with the help and care of my official editor (and with the vicious and horribly accurate criticism of Hurwitz, mentioned previously) for the past three years.

It took a long time to settle on a title: 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos. Why did that one rise up above all others? First and foremost, because of its simplicity. It indicates clearly that people need ordering principles, and that chaos otherwise beckons. We require rules, standards, values—alone and together. We’re pack animals, beasts of burden. We must bear a load, to justify our miserable existence. We require routine and tradition. That’s order. Order can become excessive, and that’s not good, but chaos can swamp us, so we drown—and that is also not good. We need to stay on the straight and narrow path. Each of the twelve rules of this book—and their accompanying essays—therefore provide a guide to being there. “There” is the dividing line between order and chaos. That’s where we are simultaneously stable enough, exploring enough, transforming enough, repairing enough, and cooperating enough. It’s there we find the meaning that justifies life and its inevitable suffering. Perhaps, if we lived properly, we would be able to tolerate the weight of our own self-consciousness. Perhaps, if we lived properly, we could withstand the knowledge of our own fragility and mortality, without the sense of aggrieved victimhood that produces, first, resentment, then envy, and then the desire for vengeance and destruction. Perhaps, if we lived properly, we wouldn’t have to turn to totalitarian certainty to shield ourselves from the knowledge of our own insufficiency and ignorance. Perhaps we could come to avoid those pathways to Hell—and we have seen in the terrible twentieth century just how real Hell can be.

I hope that these rules and their accompanying essays will help people understand what they already know: that the soul of the individual eternally hungers for the heroism of genuine Being, and that the willingness to take on that responsibility is identical to the decision to live a meaningful life.

If we each live properly, we will collectively flourish.

Best wishes to you all, as you proceed through these pages.

Dr. Jordan B. Peterson

Clinical Psychologist and Professor of Psychology

RULE 1

Stand up straight with your shoulders back

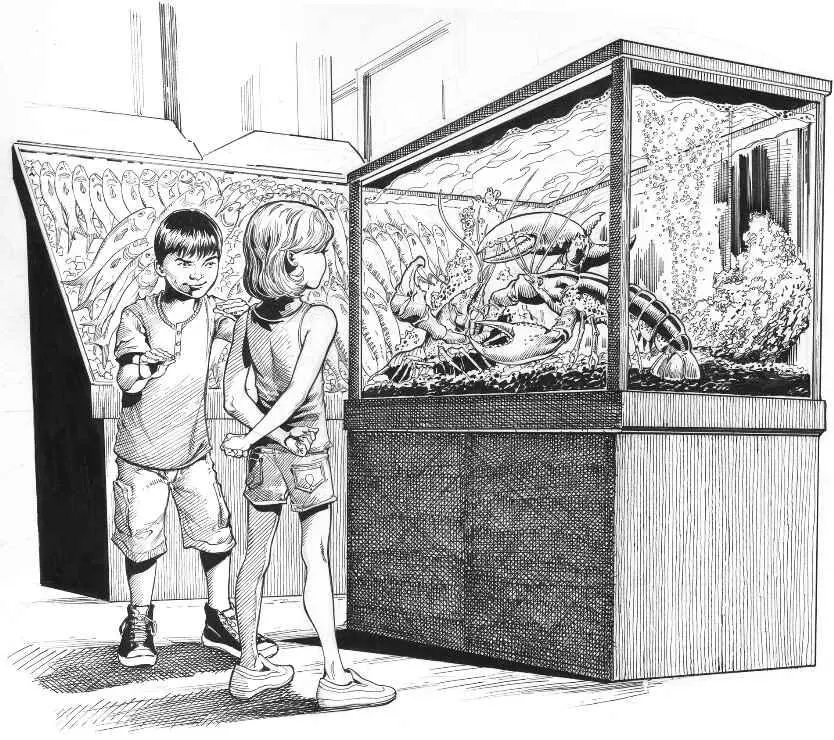

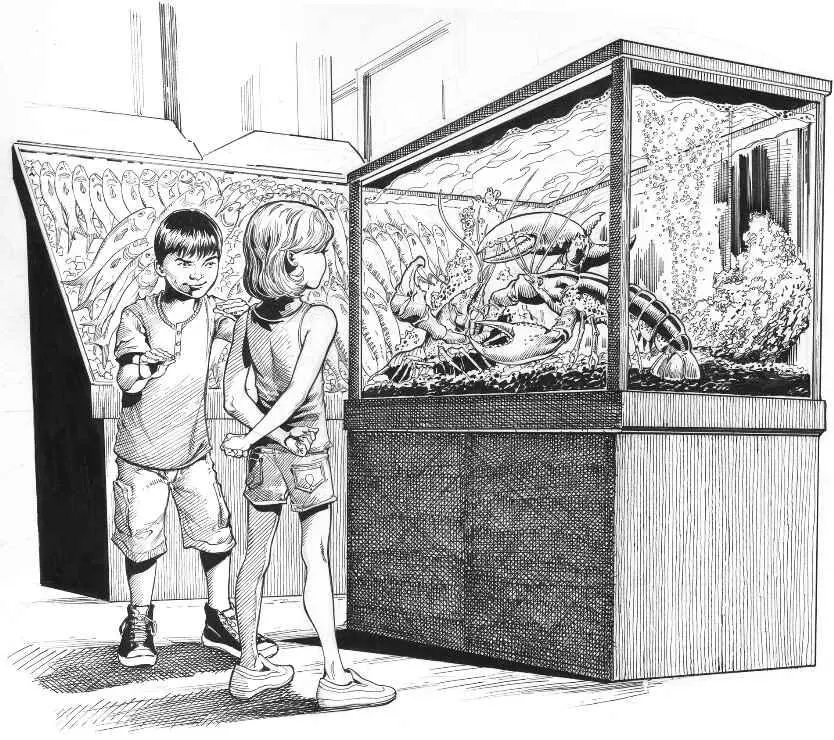

If you are like most people, you don’t often think about lobsters [18002] If you want to do some serious thinking about lobsters, this is a good place to start: Corson, T. (2005). The secret life of lobsters: How fishermen and scientists are unraveling the mysteries of our favorite crustacean . New York: Harper Perennial.

—unless you’re eating one. However, these interesting and delicious crustaceans are very much worth considering. Their nervous systems are comparatively simple, with large, easily observable neurons, the magic cells of the brain. Because of this, scientists have been able to map the neural circuitry of lobsters very accurately. This has helped us understand the structure and function of the brain and behaviour of more complex animals, including human beings. Lobsters have more in common with you than you might think (particularly when you are feeling crabby—ha ha).

Lobsters live on the ocean floor. They need a home base down there, a range within which they hunt for prey and scavenge around for stray edible bits and pieces of whatever rains down from the continual chaos of carnage and death far above. They want somewhere secure, where the hunting and the gathering is good. They want a home.

This can present a problem, since there are many lobsters. What if two of them occupy the same territory, at the bottom of the ocean, at the same time, and both want to live there? What if there are hundreds of lobsters, all trying to make a living and raise a family, in the same crowded patch of sand and refuse?

Other creatures have this problem, too. When songbirds come north in the spring, for example, they engage in ferocious territorial disputes. The songs they sing, so peaceful and beautiful to human ears, are siren calls and cries of domination. A brilliantly musical bird is a small warrior proclaiming his sovereignty. Take the wren, for example, a small, feisty, insect-eating songbird common in North America. A newly arrived wren wants a sheltered place to build a nest, away from the wind and rain. He wants it close to food, and attractive to potential mates. He also wants to convince competitors for that space to keep their distance.

My dad and I designed a house for a wren family when I was ten years old. It looked like a Conestoga wagon, and had a front entrance about the size of a quarter. This made it a good house for wrens, who are tiny, and not so good for other, larger birds, who couldn’t get in. My elderly neighbour had a birdhouse, too, which we built for her at the same time, from an old rubber boot. It had an opening large enough for a bird the size of a robin. She was looking forward to the day it was occupied.

A wren soon discovered our birdhouse, and made himself at home there. We could hear his lengthy, trilling song, repeated over and over, during the early spring. Once he’d built his nest in the covered wagon, however, our new avian tenant started carrying small sticks to our neighbour’s nearby boot. He packed it so full that no other bird, large or small, could possibly get in. Our neighbour was not pleased by this pre-emptive strike, but there was nothing to be done about it. “If we take it down,” said my dad, “clean it up, and put it back in the tree, the wren will just pack it full of sticks again.” Wrens are small, and they’re cute, but they’re merciless.

Читать дальше