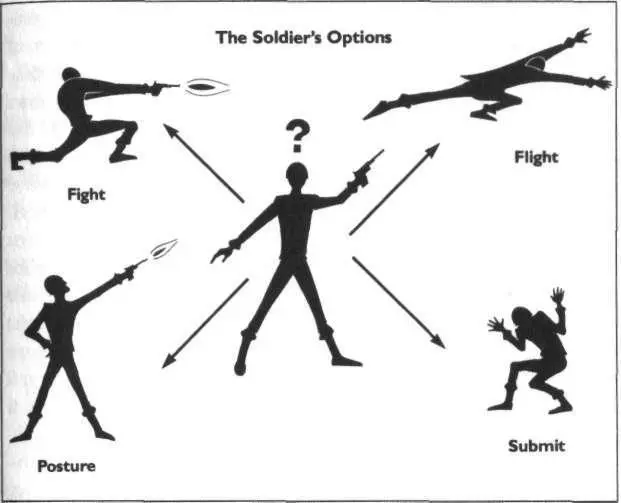

There is a clear distinction between actual violence and posturing. Oxford social psychologist Peter Marsh notes that this is true in New York street gangs, it is true in “so-called primitive tribesmen and warriors,” and it is true in almost any culture in the world. All have the same “patterns of aggression” and all have “very orchestrated, highly ritualized” patterns of posturing, mock battle, and submission. These rituals restrain and focus the violence on relatively harmless posturing and display. What is created is a “perfect illusion of violence.” Aggression, yes. Competitiveness, yes. But only a “very tiny, tiny level” of actual violence.

“There is,” concludes Gwynne Dyer, “the occasional psychopath who really wants to slice people open,” but most of the participants are really interested in “status, display, profit, and damage limitation.” Like their peacetime contemporaries, the kids who have fought in close combat throughout history (and it is kids, or adolescent males, whom most societies traditionally send off to do their fighting), killing the enemy was the very least of their intentions. In war, as in gang war, posturing is the name of the game.

In this account from Paddy Griffith’s Battle Tactics of the Civil War, we can see the effective use of verbal posturing in the thick woods of the American Civil War’s Wilderness campaign:

The yellers could not be seen, and a company could make itself sound like a regiment if it shouted loud enough. Men spoke later of various units on both sides being “yelled” out of their positions.

In such instances of units being yelled out of positions, we see posturing in its most successful form, resulting in the opponent’s selection of the flight option without even attempting the fight option.

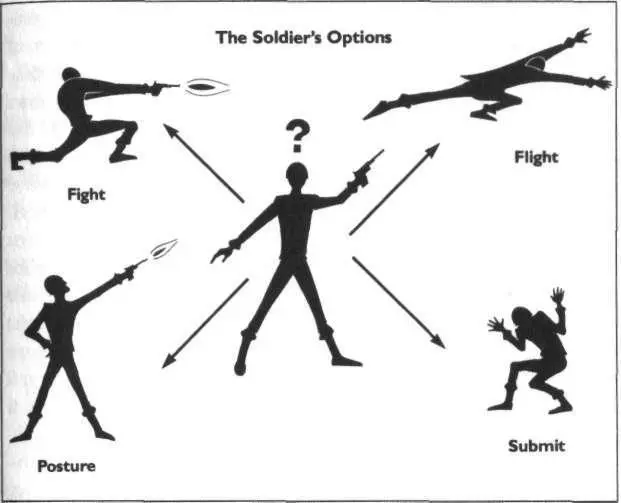

Adding the posture and submission options to the standard fight-or-flight model of aggression response helps to explain many of the actions on the battlefield. When a man is frightened, he literally stops thinking with his forebrain (that is, with the mind of a human being) and begins to think with the midbrain (that is, with the portion of his brain that is essentially indistinguishable from that of an animal), and in the mind of an animal it is the one who makes the loudest noise or puffs himself up the largest who will win.

Posturing can be seen in the plumed helmets of the ancient Greeks and Romans, which allowed the bearer to appear taller and therefore fiercer to his foe, while the brilliantly shined armor made him seem broader and brighter. Such plumage saw its height in modern history during the Napoleonic era, when soldiers wore bright uniforms and high, uncomfortable shako hats, which served no purpose other than to make the wearer look and feel like a taller, more dangerous creature.

In the same manner, the roars of two posturing beasts are exhibited by men in battle. For centuries the war cries of soldiers have made their opponents’ blood run cold. Whether it be the battle cry of a Greek phalanx, the “hurrah!” of the Russian infantry, the wail of Scottish bagpipes, or the Rebel yell of our own Civil War, soldiers have always instinctively sought to daunt the enemy through nonviolent means prior to physical conflict, while encouraging one another and impressing themselves with their own ferocity and simultaneously providing a very effective means of drowning the disagreeable yell of the enemy.

A modern equivalent to the Civil War occurrence mentioned above can be seen in this Army Historical Series account of a French battalion’s participation in the defense of Chipyong-Ni during the Korean War:

The [North Korean] soldiers formed one hundred or two hundred yards in front of the small hill which the French occupied, then launched their attack, blowing whistles and bugles, and running with bayonets fixed. When this noise started, the French soldiers began cranking a hand siren they had, and one squad started running toward the Chinese, yelling and throwing grenades far to the front and to the side. When the two forces were within twenty yards of each other the Chinese suddenly turned and ran in the opposite direction. It was all over within a minute.

Here again we see an incident in which posturing (involving sirens, grenade explosions, and charging bayonets) by a small force was sufficient to cause a numerically superior enemy force to hastily select the flight option.

With the advent of gunpowder, the soldier has been provided with one of the finest possible means of posturing. “Time and again,” says Paddy Griffith,

we read of regiments [in the Civil War] blazing away uncontrollably, once started, and continuing until all ammunition was gone or all enthusiasm spent. Firing was such a positive act, and gave the men such a physical release for their emotions, that instincts easily took over from training and from the exhortations of officers.

Gunpowder’s superior noise, its superior posturing ability, made it ascendant on the battlefield. The longbow would still have been used in the Napoleonic Wars if the raw mathematics of killing effectiveness was all that mattered, since both the longbow’s firing rate and its accuracy were much greater than that of a smoothbore musket. But a frightened man, thinking with his midbrain and going “ploink, ploink, ploink” with a bow, doesn’t stand a chance against an equally frightened man going “BANG! BANG!” with a musket.

Firing a musket or rifle clearly fills the deep-seated need to posture, and it even meets the requirement of being relatively harmless when we consider the consistent historical occurrences of firing over the enemy’s head, and the remarkable ineffectiveness of such fire.

Ardant du Picq became one of the first to document the common tendency of soldiers to fire harmlessly into the air simply for the sake of firing. Du Picq made one of the first thorough investigations into the nature of combat with a questionnaire distributed to French officers in the 1860s. One officer’s response to du Picq stated quite frankly that “a good many soldiers fired into the air at long distances,” while another observed that “a certain number of our soldiers fired almost in the air, without aiming, seeming to want to stun themselves, to become drunk on rifle fire during this gripping crisis.”

Paddy Griffith joins du Picq in observing that soldiers in battle have a desperate urge to fire their weapons even when (perhaps especially when) they cannot possibly do the enemy any harm. Griffith notes:

Even in the noted “slaughter pens” at Bloody Lane, Marye’s Heights, Kennesaw, Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor an attacking unit could not only come very close to the defending line, but it could also stay there for hours — and indeed for days — at a time. Civil War musketry did not therefore possess the power to kill large numbers of men, even in very dense formations, at long range. At short range it could and did kill large numbers, but not very quickly [emphasis added].

Griffith estimates that the average musket fire from a Napoleonic or Civil War regiment (usually numbering between two hundred and one thousand men) firing at an exposed enemy regiment at an average range of thirty yards, would usually result in hitting only one or two men per minute! Such firefights “dragged on until exhaustion set in or nightfall put an end to hostilities. Casualties mounted because the contest went on so long, not because the fire was particularly deadly.”

Thus we see that the fire of the Napoleonic- and Civil War-era soldier was incredibly ineffective. This does not represent a failure on the part of the weaponry. John Keegan and Richard Holmes in their book Soldiers tell us of a Prussian experiment in the late 1700s in which an infantry battalion fired smoothbore muskets at a target one hundred feet long by six feet high, representing an enemy unit, which resulted in 25 percent hits at 225 yards, 40 percent hits at 150 yards, and 60 percent hits at 75 yards. This represented the potential killing power of such a unit. The reality is demonstrated at the Battle of Belgrade in 1717, when “two Imperial battalions held their fire until their Turkish opponents were only thirty paces away, but hit only thirty-two Turks when they fired and were promptly overwhelmed.”

Читать дальше