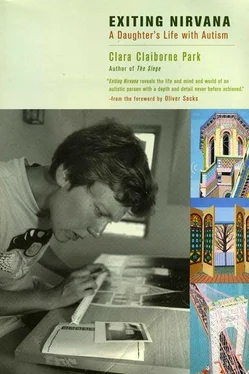

Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Психология, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Exiting Nirvana

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0-316-69117-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Exiting Nirvana: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Exiting Nirvana»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

All illustrations are by Jessy Park.

Exiting Nirvana — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Exiting Nirvana», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Still, it took many, many more years before Jessy was at home enough in language to make a joke in words. At first it was hard to tell if they were really jokes, as when, seeing me about to sneeze, she said she’d read, not my mind (we’d talked about that) but my nose. But we laughed, and she did too, clearly enjoying the unexpected thing she’d done with words. Word play became more frequent. Though our cat’s name was Daisy, we often called her «Kitty dear», and Jessy echoed us. One day she saw a daisy in a field and addressed it as «Kitty dear». A simple (mis)association of ideas? A prepun? She laughed, at any rate, and that made it a joke. She was ready for puns; she learned the word at once. «Two days ago I saw somebody cut hair in the mailroom — ‘just a hair.’ That is a pun!» And it was; she’d remembered her father’s way of saying «just a little bit».

The pun, I was told as a child, is the lowest form of humor, and hers are very simple. «Cold pills is pills that are out in the cold!» «The microbus is the bus with microbes in it!» But this one shows real observation. «Eclipse Rum» — the label caught her eye, at a time when she resonated to anything about eclipses. «Eclipse can eclipse the pain and eclipse the insomnia. That is a pun».

Indeed, and more than a pun. It is a step beyond the literal, into further, richer dimensions of language. No giant step, however; Jessy doesn’t take giant steps. Twelve years have passed since then. Eclipses have lost their fascination; these days it’s anything to do with Merrill Lynch. So we read from the morning paper: the company is downsizing. «A certain number of people are going to be cut». «Cut?!!» The astonishment in her voice makes it plain: the autistic literalism survives. They are to be mastered one by one, the slippery ways of words.

Some, however, she will not master. After forty years we know that. I need to say more about Jessy’s difficulty with pronouns — a difficulty which, though it may seem too specific to be of general significance, points far beyond itself to some of the most important areas of current research, into the psychological and biological nature of autism.

Among the autistic characteristics that Leo Kanner noted in the brilliantly observed paper in which he first identified the autistic syndrome was «pronominal reversal». He based his report on eleven cases; along with literal and stereotyped language, he noted pronominal reversal in eight of them — and the other three had no language at all.

There is no difficulty with plurals and tenses. But the absence of spontaneous sentence formation and the echolalia type of reproduction [have]. given rise to a peculiar grammatical phenomenon. Personal pronouns are repeated just as heard [emphasis his], with no change to suit the altered situation. The child, once told by his mother, «Now I will give you your milk», expresses the desire for milk in exactly the same words. Consequently he comes to speak of himself as «you», and of the person addressed as «I»… There is a set, not-to-be-changed phrase for every specific occasion. [10] Kanner, op. cit., p. 43.

Just so; autistic speech begins as echo. When Jessy at last began to request things, that’s what we’d hear: «You want a cookie?» She was six. She was eight when I finished the first long, slow chapter on her speech, and she still did not refer to herself as «I». By then, however, she echoed the word — and reversed the meaning. «I» was her mother. That, after all, was what she heard me say.

Since then there has been great progress. Her sentences are longer and more complex. They are fairly correct grammatically. They reach beyond herself to other people. Yet even so, these are the kinds of things that may come out when she has to deal with pronouns:

«I think I will eat with us», she says. «I» is securely in place, but «us» is an uneasy surrogate for the plural «you» that should denote me and her father. Even the «I» may get lost: «You wrote you a check». Who did? It was she who had paid me for her share of the groceries. «We will have to borrow our car». It was the neighbor who needed our car. Two pronouns at the same time are just too hard to handle. She speaks of Miranda, her brother’s daughter, and someone asks, «Who’s Miranda?» She hesitates. Then, slowly and carefully, she replies: «I. am. my niece».

Be assured, Jessy knows she isn’t her niece. Although eager psychoanalysts for years took pronominal reversal as evidence of «early ego failure», Jessy has anything but a weak ego. Still, they were right in suspecting that something more significant was going on than peculiar grammar, more pervasive than a mix-up of two pronouns. Yet however tempting «I» and «you» might be to ego psychologists, they are only the tip of the iceberg. Jessy has even more trouble with «we» and «our» and «us», with «they» and «their», with «his» and «hers», even with «he» and «she». I hear her answering the phone, groping for the words to tell a caller her father’s not home. It’s going slowly, so I try to help. «Say he’s not home and can you take a message». Jessy alters the primary pronoun; she’s learned that much. But what results is this: «She’s not home, and can you take a message».

So what is going on? «The pronominal fixation», wrote Kanner, «remains until about the sixth year of life, when the child gradually learns to speak of himself in the first person, and the person addressed in the second person». [11] Ibid., pp. 43–44.

At six, when Kanner’s children had sorted out their pronouns and had «no difficulty with plurals and tenses», Jessy’s difficulties were just beginning. Obviously, their speech handicap was less severe than hers. Because it was less severe, Kanner could think of pronominal reversal as an isolated — and temporary — grammatical oddity. And because he noticed no difficulties in plurals and tenses, he could not see how closely all these — and other — characteristics of autistic speech are related, or the deeper problems they point to.

Consider these examples, all from Jessy’s third decade. «I better remind Daddy about my dental appointment». «We are having chicken livers for dinner». «My supervisor said I’m going away for Christmas». The first two seem to be perfectly ordinary statements, and the third, though a little odd, is at least possible. Except that it wasn’t Jessy’s appointment, it was her father’s. Except that she’d already had dinner; she wasn’t included in that «we». Except that it was the supervisor, not Jessy, who was going away. Jessy knew all these things; she is the last person to be confused about matters of fact. It was the words, the slippery, shifting words, she couldn’t handle.

Kanner had it right. She couldn’t change the pronoun «to suit the altered situation», least of all when she had to manage two pronouns and correctly relate them to each other. Pronouns shift. Nouns stay still. She had no trouble with «Miranda», as she had spoken her own name years before she referred to herself as «I».

The altered situation: that’s the key. And what has altered the situation? Its external constituents are unchanged: the dental appointment, the chicken livers, the vacation, even the people referred to. What has changed is the interior situation, the point of view. Point of view is what determines the choice of pronoun. His appointment. You — you two — are having chicken livers. She’s going away. Pronouns must be adjusted, changed from first to second or third person, from singular to plural, often both at the same time. It’s complicated even to write about; how do little children manage to learn to do it?

Recent research suggests that they do it, easily and naturally, because they have a «theory of mind». Never mind the grandeur of the phrase; consider instead the implications of the experiment Uta Frith and her colleagues reported in 1985. The situation is simple: an experimenter, a child, and two puppets, Sally and Anne. While the child watches, the puppets act out a little drama. Dr. Frith describes it: «Sally has a basket, Anne has a box. Sally puts a marble into her basket. Sally goes out for a walk. While Sally is out of the room, Anne (naughty Anne!) takes the marble from the basket and puts it into her own box. Now it is time for Sally to come back. Sally wants to play with her marble». Now the investigator is ready to ask the key questions: «Where will Sally think her marble is? Where will she look?» [12] Frith, in Autism and Asperger Syndrome, p. 18.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Exiting Nirvana» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Майкл Азеррад - Come as you are - история Nirvana, рассказанная Куртом Кобейном и записанная Майклом Азеррадом [litres]](/books/392533/majkl-azerrad-come-as-you-are-istoriya-nirvana-ra-thumb.webp)

![Эверетт Тру - Nirvana - Правдивая история [litres]](/books/399241/everett-tru-nirvana-pravdivaya-istoriya-litres-thumb.webp)