PART II

Physician, Heal Thyself

The meaning of all addictions could be defined as endeavours at controlling our life experiences with the help of external remedies…. Unfortunately, all external means of improving our life experiences are double-edged swords: they are always good and bad. No external remedy improves our condition without, at the same time, making it worse.

THOMAS HORA, M.D.

Beyond the Dream: Awakening to Reality

CHAPTER 9

Takes One to Know One

It’s hard to get enough of something that almost works.

VINCENT FELITTI, M.D.

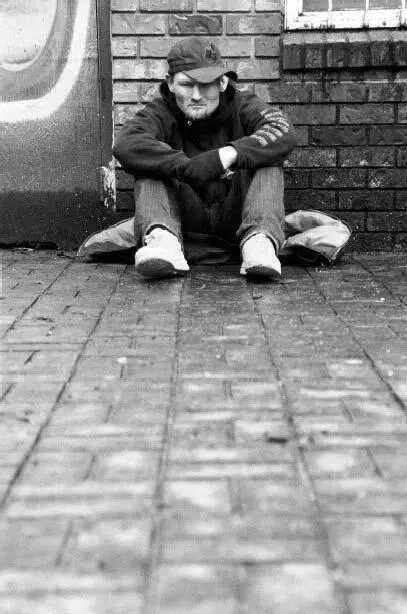

It’s not one of my Portland days, but the work won’t leave me alone. Susan, our health coordinator, rings me on my cell, sounding exasperated: “Mr. Grant is back here at the hotel. What should we do?” I stifle a profanity. I have no patience for treating addiction today; I’m supposed to be at home, writing a book about it.

“Mr. Grant” is Gary, a barrel-bellied, grey-bearded bear of a man, with HIV and diabetes—both risk factors for infection. Neither condition deters him from injecting any accessible vein in his foot with cocaine. His upper-arm vessels are too scarred and corroded by chemicals to serve. A large ulcer is eroding his right big toe, its black base oozing with the breakdown products of dead flesh. For two weeks we’d been urging Gary to accept hospitalization, since it was still possible that intravenous antibiotics could save his toe.

“Yes, tomorrow,” he’d say. But tomorrow never came.

Four days ago, late on Friday evening, I sought him out in his eighth-floor room. The homecare nurses treating the wound had called in desperation: “Would you commit him on mental health grounds?” Loath to use that ultimate weapon on someone in no way psychotic—just addicted—I promised to see what I could do. I was prepared to pull out the pink slip of involuntary committal, but only as a final resort.

Gary had just come in from scoring a deal. Like many in the Downtown Eastside, he supports his habit with what his long-time friend Stevie once mockingly called “a self-initiated, self-organized marketing endeavour.” He makes just enough to keep himself in his substances of choice. Only two weeks before, Stevie had died of liver cancer. Gary had been very close to her—“a fellowship of free trade advocates” in Stevie’s words. Intensely distressed by Stevie’s demise, Gary had been on an extended cocaine binge since her death.

“Everybody’s worried about you, Gary,” I said. “That’s why I’m here.”

“Well, I’m worried about me, too.”

Just then Kenyon appeared in the doorway, leaning on his cane.

“Got any crystal, Gary?” he asked in his keening voice, slurring his words and seemingly oblivious of my presence. “Fuck off, you idiot. Can’t you see the doctor’s here?” “Okay,” Kenyon replied, soothingly, as if humouring an obstreperous little child. “I’ll be back.” He hobbled off, the tap-tap of his wooden cane on cement echoing away down the hall.

“You could lose your foot,” I resumed. “The gangrene is spreading.”

“I can see that. If you tell me I have to go to hospital, I will. “

“I appreciate your confidence in my opinion. I only wish I could be equally confident in your capacity to fulfill your intentions, honourable as they are.” The bite in my tone is deliberate. “You promised the same last week, and since then the ulcer has doubled in size. Will you go tonight?”

“Ah, not on a Friday night. I’ll be in Emerg until the morning. Tomorrow.”

“Gary, I hate to even say this, but if by tomorrow at eleven a.m. you haven’t left for the E.R., I’m going to declare you mentally incompetent and commit you on the grounds that you’re endangering your own health. You want the truth of it? I don’t think for a minute you’re crazy, but you’re acting crazy. So I’ll do it.”

It’s the same line I’d used on Devon a few months back when he’d refused treatment for a spinal abscess that could have left him quadriplegic. I rarely resort to such threats, as I find them ethically unjustifiable and, for the most part, valueless in practice. I did hospitalize Devon under duress, however, and he’s thanked me for that since, many times over.

Next morning Gary did get himself to hospital, only to be discharged with an ineffective antibiotic. The hotel staff had not called me in time, and I’d had no opportunity to communicate with the E.R. physician. Arranging Gary’s admission and linking him up with the appropriate specialists had been Sunday’s work. And now, on Tuesday, he’d absconded from the HIV ward and fled back to the Portland. He’d passed the point of antibiotic salvage. Toe amputation was scheduled for Wednesday.

Although it’s my mid-week writing morning, Susan believes Gary’s situation is too delicate for the doctor who’s filling in for me. I agree to drop in and, if compelled, to play the pink-slip card. I hear Susan’s voice soften in relief. Heading downtown, I’m thrown a curveball by the addicted voice in my own head. “Sikora’s? Just for a minute?” No, I tell myself, tempted as I am, that would be impossible to justify. I arrive at the Portland to find that Gary, mercifully, has returned to hospital in the nick of time, just before he would have lost his bed. Good, I think to myself. I’m tired of having to drag people to healing by the scruff of their neck. With that, I drive away from the Downtown Eastside, that woeful planet of drug users and dealers who hustle, grind, cheat and manipulate 24/7 to feed their habits.

I’m on my way to St. Paul’s Hospital, where, in addition to my Portland work, I provide medical care to psychiatric inpatients. I take my usual route: exit the Portland parking garage, left out of the alley onto Abbott, right onto Pender. Two blocks past Abbott, my pulse quickens as I approach Sikora’s—without doubt one of the world’s great classical music stores.

Agitating my mind and body are thoughts of a CD of operatic favourites by the tenor Rolando Villazón. I listened to selections yesterday when I went to the store to pay off my latest debt, but resisted the urge to purchase. Today it’s clamouring for me to return and pick it up. I must have it and I must have it now. The desire first arises as a thought and rapidly transforms itself into a concrete object in my mind, with a weight and a pull. It generates an irresistible gravitational field. The tension is relieved only when I succumb.

An hour later, I leave Sikora’s with the Villazón disc and several others. Hello, my name is Gabor, and I am a compulsive classical music shopper.

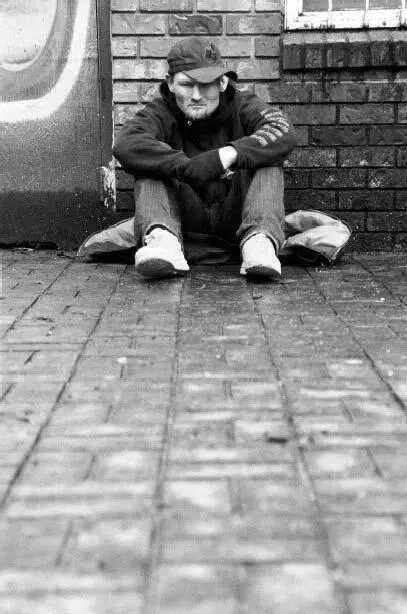

A word before I continue: I do not equate my music obsession with the life-threatening habits of my Portland patients. Far from it. My addiction, though I call it that, wears dainty white gloves compared to theirs. I’ve also had far more opportunity to make free choices in my life, and I still do. But if the differences between my behaviours and the self-annihilating life patterns of my clients are obvious, the similarities are illuminating—and humbling. I have come to see addiction not as a discrete, solid entity—a case of “Either you got it or you don’t got it”—but as a subtle and extensive continuum. Its central, defining qualities are active in all addicts, from the honoured workaholic at the apex of society to the impoverished and criminalized crack fiend who haunts Skid Row. Somewhere along that continuum I locate myself.

Читать дальше