These megatrends have personal consequences. Honestly, for the long haul, I’ve begun socking away shares of pharmaceutical company stock. Because beginning right about now, the world is starting to fill up with old people.

Demography just might be the most fascinating academic subject you’ve never studied. Underneath its dull name and dry statistics lie gripping stories of sex and death, of the rise and fall of communities, of why migrants choose to pick up and move, of the futures for our retirements and for our children. It uncovers big surprises like the myth of the American melting pot. 75Although combing through census and national registry databanks on numbers of births, deaths, and marriages may not sound very fun, a new world is revealed. These data comprise a road map of our future still wired into today.

Consider the “baby boomer” phenomenon—that is, the post-World War II baby boom. Like a snake swallowing a big meal, this age bulge has worked its way through the decades, triggering all manner of economic and cultural transformations along the way. Many of them—like demand for doctors, vacation getaways, and Viagra as the boomers now enter their sixties—have been anticipated for years. Like all baby booms, it had a softer “baby echo” that cropped up a generation later—again, predictable.

“Population momentum” is another example of how demographic futures can be foreseen. Even if a society’s average fertility rate 76suddenly falls, its population will continue to grow twenty years later owing to the abundance of new parents carried forward from when fertility rates were high. 77This works in the other direction, too, meaning that elderly countries will keep shrinking even if fertility rises, owing to a small cohort of parents born when fertility rates were still low.

The unprecedented explosion of people on Earth happened because births began outnumbering deaths, but there’s more to it than that. The “Demographic Transition” concept described in Chapter 1 emerged from what transpired in Europe and the United States. And it appears to now be unfolding in the rest of the world as well. Recall that the Demographic Transition has four stages:

1. High and similar rates of birth and death (e.g., the preindustrial era, with a small and relatively stable total human population); followed by

2. Falling deaths but not births (initiating a population explosion); followed by

3. Falling births (still exploding, but decelerating); and finally

4. Low and similar rates of birth and death (population stabilization at a new, higher total number).

Most OECD countries have now passed through these stages and—except for those allowing high levels of immigration like the United States—have stabilizing or even falling populations. Most developing nations, however, are still in Stage 2 or early Stage 3. Thus, our run-up in global population is still under way.

Once a population enters Stage 3 its net rate of growth starts to slow, and this has generally been happening, beginning at different times and to varying degrees, for most of the world. On average, growth rates in developing countries have decreased from around +2.3% per year in 1950 to +1.8% in 2007. Expressed as “doubling times” (the number of years needed for a population to double), that means we have slowed from doubling our developing world population about every thirty years in 1950 to every forty years in 2007.

As we saw in Chapter 1, urbanization, modernization, and the empowerment of women push fertility rates downward, thus ushering in the final stage of the Demographic Transition. Put another way, the urbanization of society—if also associated with modernization and women’s rights—helps slow the rate of growth. There are, of course, exceptions to this tendency, but as these phenomena continue to expand throughout the developing world, the global population explosion so feared by Thomas Malthus and Paul Ehrlich is expected to decelerate. Already, in late-stage, low-immigration developed countries like Japan and Italy, and in regions like Eastern Europe, populations have not only stabilized but are falling. Assuming that fertility rates continue to drop as they are now, we are heading toward a total world population of around 9.2 billion in 2050, at which point we will still be growing but about half as fast as we are today. 78

One of the most profound long-term effects of women having fewer babies is to skew societal age structures toward the elderly (the pulse of babies from population momentum is only temporary). That is precisely what has now begun, in varying stages, all around the world (improving health care, of course, also extends our life spans, thus increasing the proportion of elderly even more). Demographers agree that we are racing forward to not only a more urban world, but a grayer one. This, too, is unprecedented in the history of humankind. For 99.9% of the time we humans have existed on Earth, our average life expectancy was 30 years or less. Archaeologists have never dug up the prehistoric remains of anyone over 50. 79

This aging will hit some places faster and harder than others. With a median age of 44.6 years 80Japan is the world’s most elderly country today. In contrast, the median age in Pakistan is just 22.1 years, almost half that of Japan. Pakistan is youthful; Japan is full of geezers. But both places will become grayer during the next forty years. By 2050 the median Pakistani age will rise twelve years to 34. Japan’s will rise another decade to 55.

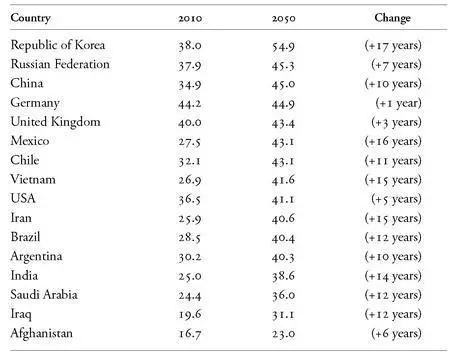

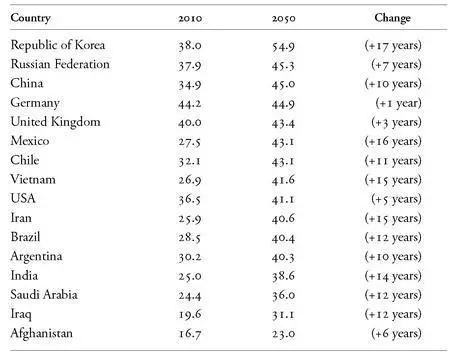

When I was young I remember seeing magazine advertisements targeting people who planned to retire at 55. In forty years fully half of all Japanese will be at least that old. On the following page, a table shows how the graying trend will transpire for a few other countries over the next forty years. 81

As seen plainly on this table from just sixteen examples, there are large age contrasts around the world today and even larger ones emerging in the future. Korea, Russia, and China will join Japan as the world’s great geriatric nations. Mexicans will be older than Americans. Median ages will be higher everywhere, but Korea, Vietnam, Mexico, and Iran will age radically, by fifteen years or more. Only our poorest, least-developed countries—like Afghanistan, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo—will still have youthful populations in 2050; and even they will be somewhat older than today.

This patchwork of wildly contrasting age patterns around the globe is especially driven by the timing of fertility transitions—when the baby booms and echoes happened, and most importantly, when fertility rates first began to fall. 82In many OECD countries this began in the late 1950s, so the graying process is nearing its end. Median ages have already become quite high today and by 2050 will average only six years older. The same process

Some World Aging Patterns by 2050

(median age, in years)

( Source: United Nations Population Division)

is now under way in developing countries, where fertility drops beginning in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s will unleash successive waves of aging over the planet for the next forty years.

In his 1982 film Blade Runner, director Ridley Scott imagined that my home city of Los Angeles would be filled up with Japanese people by the year 2019. In light of Japan’s economic might at the time, it’s not hard to see where the idea came from. But Mr. Scott should have consulted a demographer, because I just don’t see where all those Japanese settlers will come from. Over the next forty years, Japan is going to lose about 20% of her population.

Читать дальше