Christopher alexander - A pattern language

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Christopher alexander - A pattern language» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Прочая научная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A pattern language

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A pattern language: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A pattern language»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A pattern language — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A pattern language», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Examples of ecologically useful animals in a city: horses, ponies, donkeys—for local transportation and sport. Pigs—to recycle garbage and for meat. Ducks and chickens—as a source of eggs and meat. Cows—for milk. Goats—milk. Bees—honey and pollination of fruit trees. Birds—to maintain insect balance.

There are essentially two difficulties to overcome, (i) Many of these animals have been driven out of cities by law because they interrupt traffic, leave dung on the street, and carry disease. (2) Many of the animals cannot survive without protection under modern urban conditions. It is necessary to make specific provisions to overcome these difficulties.

Therefore:

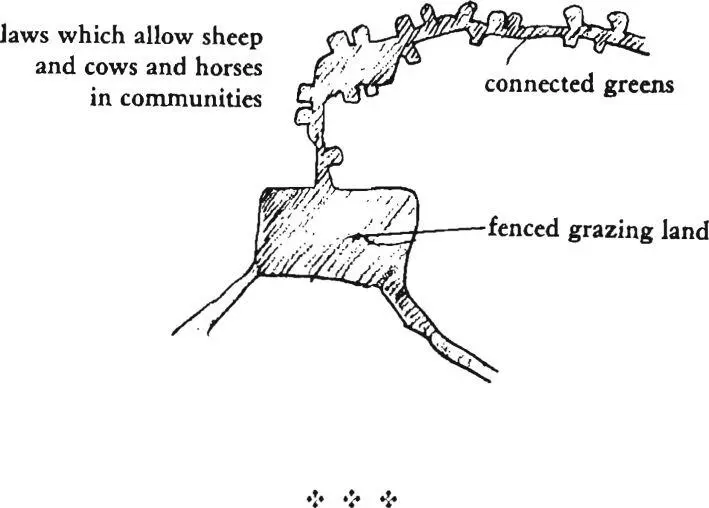

Make legal provisions which allow people to keep any animals on their private lots or in private stables. Create a piece of fenced and protected common land, where animals

TOWNS

are free to graze, with grass, trees, and water in it. Make at least one system of movement in the neighborhood which is entirely asphalt-free—where dung can fall freely without needing to be cleaned up.

Make sure that the green areas—green streets (51), accessible green (60)—are all connected to one another to form a continuous swath throughout the city for domestic and wild animals. Place the animal commons near a children’s home and near the local schools, so children can take care of the animals —children’s home (86) ; if there is a lot of dung, make sure that it can be used as a fertilizer—compost (178). . . .

374

within the framework of the common land , the clusters and the work communities )encourage transformation of the smallest independent social institutions : the families yworkgroups , and gathering places.

Fir sty the family, in all its forms;

75 . THE FAMILY

76. HOUSE FOR A SMALL FAMILY

77. HOUSE FOR A COUPLE

78. HOUSE FOR ONE PERSON

79. YOUR OWN HOME

THE POETRY OF THE LANGUAGE

greater, and more personal things than any rose—and the poem illuminates the person, and the rose, because of this connection. The connection not only illuminates the words, but also illuminates our actual lives.

O Rose thou art sick. The invisible worm, That flies in the night In the howling storm:

Has found out thy bed Of crimson joy:

And his dark secret love Does thy life destroy.

WILLIAM BLAKE

The same exactly, happens in a building. Consider, for example, the two patterns bathing room(144) and still water(71). One defines a part of a house where you can bathe yourself slowly, with pleasure, perhaps in company - a place to rest your limbs, and to relax. The other is a place in a neighborhood, where this is water to gaze into, perhaps to swim in, where children can sail boats, and splash about, which nourishes those parts of ourselves which rely on water as one of the great elements of the unconscious.

Suppose now, that we make a complex of buildings where individual bathing rooms are somehow connected to a common pond, or lake, or pool—where the bathing room merges with this common place; where there is no sharp distinction between the individual and family processes of the bathing room, and the common pleasure of the common pool. In this place, these two patterns

xlii

| 75 the family* |

|---|

|

376

. . . assume now, that you have decided to build a house for yourself. If you place it properly, this house can help to form a cluster, or a row of houses, or a hill of houses—house cluster (37), row houses (38), housing hill (39)—or it can help to keep a working community alive—housinc in between (48). This next pattern now gives you some vital information about the social character of the household itself. If you succeed in following this pattern, it will help repair life cycle (26) and household mix (35) in your community.

The nuclear family is not by itself a viable social form.

Until a few years ago, human society was based on the extended family: a family of at least three generations, with parents, children, grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins, all living together in a single or loosely knit multiple household. But today people move hundreds of miles to marry, to find education, and to work. Under these circumstances the only family units which are left are those units called nuclear families: father, mother, and children. And many of these are broken down even further by divorce and separation.

Unfortunately, it seems very likely that the nuclear family is not a viable social form. It is too small. Each person in a nuclear family is too tightly linked to other members of the family; any one relationship which goes sour, even for a few hours, becomes critical; people cannot simply turn away toward uncles, aunts, grandchildren, cousins, brothers. Instead, each difficulty twists the family unit into ever tighter spirals of discomfort; the children become prey to all kinds of dependencies and oedipal neuroses; the parents are so dependent on each other that they are finally forced to separate.

Philip Slater describes this situation for American families and finds in the adults of the family, especially the women, a terrible, brooding sense of deprivation. There are simply not enough people around, not enough communal action, to give the ordinary

TOWNS

experience around the home any depth or richness. (Philip E. Slater, The Pursuit of Loneliness , Boston: Beacon Press, 197O, p. 67, and throughout.)

It seems essential that the people in a household have at least a dozen people round them, so that they can find the comfort and relationships they need to sustain them during their ups and downs. Since the old extended family, based on blood ties, seems to be gone—at least for the moment—this can only happen if small families, couples, and single people join together in voluntary “families” of ten or so.

In his final book, Island , Aldous Huxley portrayed a lovely vision of such a development:

“How many homes does a Palanese child have?”

“About twenty on the average.”

“Twenty? My God!”

“We all belong,” Susila explained, “to a MAC—a Mutual Adoption Club. Every MAC consists of anything from fifteen to twenty-five assorted couples. Newly elected brides and bridegrooms, old-timers with growing children, grandparents and great-grandparents— everybody in the club adopts everyone else. Besides our own blood relations, we all have our quota of deputy mothers, deputy fathers, deputy aunts and uncles, deputy brothers and sisters, deputy babies and toddlers and teen-agers.”

Will shook his head. “Making twenty families grow where only one grew before.”

“But what grew before was your kind of family. . . .” As though reading instructions from a cookery book, “Take one sexually inept wage slave,” she went on, “one dissatisfied female, two or (if preferred) three small television addicts; marinate in a mixture of Freudism and dilute Christianity; then bottle up tightly in a four-room flat and stew for fifteen years in their own juice. Our recipe is rather different: Take twenty sexually satisfied couples and their offspring; add science, intuition and humor in equal quantities; steep in Tantrik Buddhism and simmer indefinitely in an open pan in the open air over a brisk flame of affection.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A pattern language»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A pattern language» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A pattern language» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.