Christopher alexander - A pattern language

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Christopher alexander - A pattern language» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Прочая научная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A pattern language

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A pattern language: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A pattern language»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A pattern language — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A pattern language», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

208

| 39 HOUSING HILL |

|---|

|

209

. . . at the still higher densities required in the inner ring of the community’s density rings (29), and wherever densities rise above 30 houses per acre or are four stories high—four-story limit (21), the house clusters become like hills.

•£• ♦£*

Every town has places in it which are so central and desirable that at least 30-50 households per acre will be living there. But the apartment houses which reach this density are almost all impersonal.

In the pattern your own home (79), we discuss the fact that every family needs its own home with land to build on, land where they can grow things, and a house which is unique and clearly marked as theirs. A typical apartment house, with flat walls and identical windows, cannot provide these qualities.

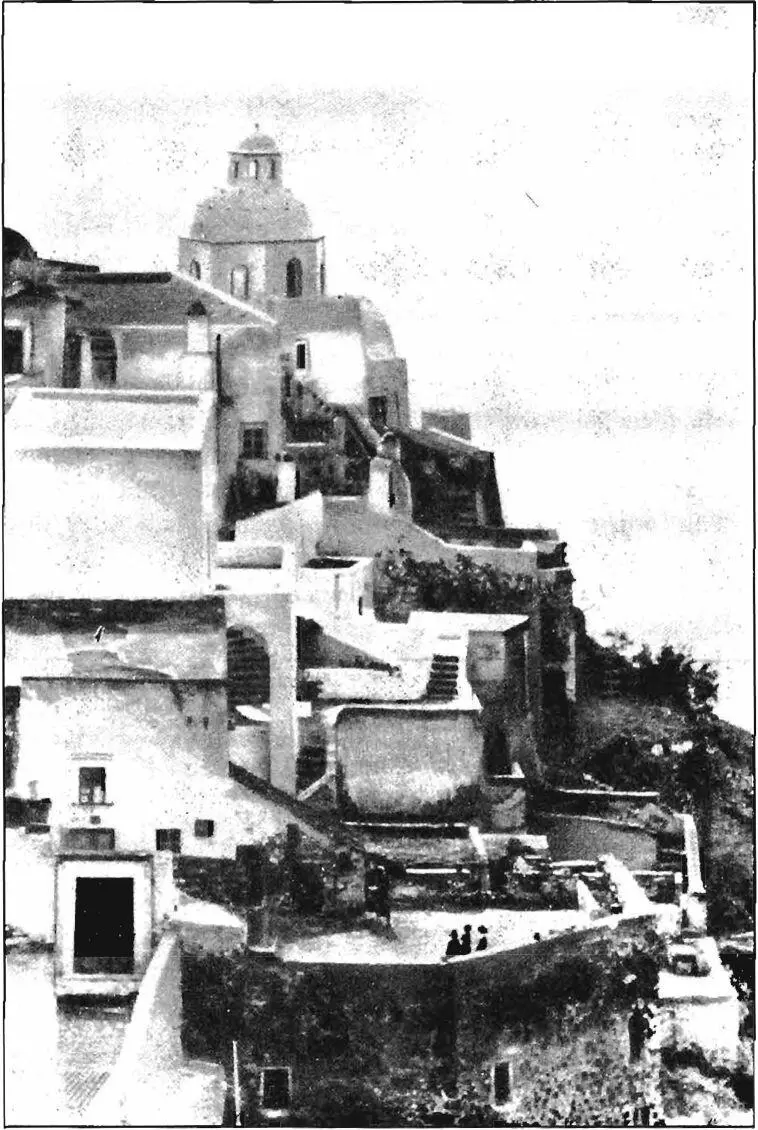

The form of the housing hill comes essentially from three requirements. First, people need to maintain contact with the ground and with their neighbors, far more contact than high-rise living permits. Second, people want an outdoor garden or yard. This is among the most common reasons for their rejecting apartment living. And third, people crave for variation and uniqueness in their homes, and this desire is almost always constrained by high-rise construction, with its regular facades and identical units.

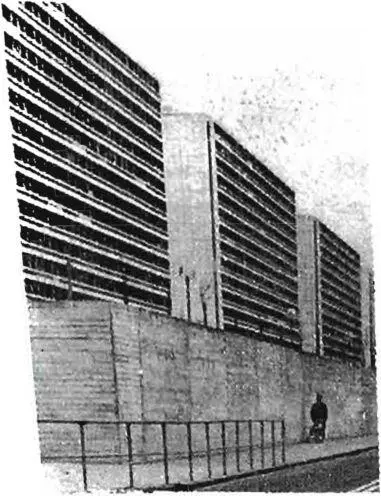

1. Connection to the ground and to neighbors. The strongest evidence comes from D. M. Fanning (“Families in Flats,” British Medical Journal , November 1967, pp. 382-86). Fanning shows a direct correlation between incidence of mental disorder and high-rise living. These findings are presented in detail in four-story limit (21). High-rise ljving, it appears, has a terrible tendency to leave people alone, stranded, in their apartments. Home life is split away from casual street life by elevators, hallways, and long stairs. The decision to go out for some public life becomes formal and awkward; and unless there is some specific task which brings people out in the world, the tendency is to stay home, alone.

39 HOUSING HILL

Farming also found a striking lack of communication between families in the high-rise flats he studied. Women and children were especially isolated. The women felt they had little reason to take the trip from their apartment to the ground, except to go shopping. They and their children were effectively imprisoned in their apartments, cut off from the ground and from their neighbors.

|

| Contact is impossible. |

It seems as if the ground, the common ground between houses, is the medium through which people are able to make contact with one another and with themselves. Living on the ground, the yards around houses join those of the neighbors, and, in the best arrangements, they also adjoin neighborhood byways. Under these conditions it is easy and natural to meet with people. Children playing in the yard, the flowers in the garden, or just the weather outside provide endless topics for conversations. This kind of contact is impossible to maintain in high-rise apartments.

2. Private gardens. In the Park Hill survey (J. F. Demors, “Park Hill Survey,” O.A.P. y February 1966, p. 235), about one-third of the high-rise residents interviewed said they missed the chance to putter around in their garden.

The need for a small garden, or some kind of private outdoor space, is fundamental. It is equivalent, at the family scale, to the biological need that a society has to be integrated with its country-

2 1 1

side—city country fingers (3). In all traditional architec tures, wherever building is essentially in the hands of the people, there is some expression of this need. The miniature gardens of Japan, outdoor workshops, roof gardens, courtyards, backyard rose gardens, communal cooking pits, herb gardens—there are thousands of examples. But in modern apartment structures this kind of space is simply not available.

3. Identity of each unit. During the course of a seminar held at the Center for Environmental Structure, Kenneth Radding made the following experiment. He asked people to draw their dream apartment, from the outside, and stuck the drawing on a small piece of cardboard. He then asked them to place the cardboard on a grid representing the facade of a huge apartment house, and asked them to move their “homes” around, until they liked the position they were in. Without fail, people wanted their apartments to be on the edge, of the building, or set off from other units by blank walls. No one wanted his own apartment to be lost in a grid of apartments.

In another survey we visited a nineteen-story apartment building in San Francisco. The building contained 190 apartments each with a balcony. The management had set very rigid restrictions on the use of these balconies—no political posters, no painting, no clothes drying, no mobiles, no barbecues, no tapestries. But even when confined by such restrictions, over half of the residents were still able, in some way, to personalize their balconies with plants in pots, carpets, and furniture. In short, in the face of the most extreme regimentation people try to give their apartments a unique face.

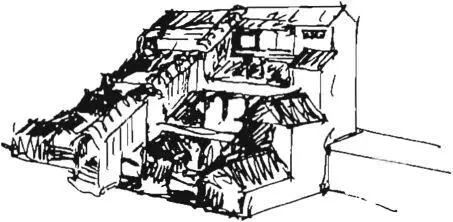

What building form is compatible with these three basic requirements? First of all, to maintain a strong and direct connection to the ground, the building must be no higher than four stories—four-story limit (21). Also, and perhaps more important, we believe that each “house” must be within a few steps of a rather wide and gradual stair that rises directly from the ground. If the stair is open, somewhat rambling, and very gradual, it will be continuous with the street and the life of the street. Furthermore, if we take this need seriously, the stair must be connected at the ground to a piece of land, owned in common

21 2 39 HOUSING HILL

by the residents—this land organized to form a semi-private green.

Concerning the private gardens. They need sunlight and privacy—two requirements hard to satisfy in ordinary balcony arrangements. The terraces must be south-facing, large, and intimately connected to the houses, and solid enough for earth, and bushes, and small trees. This suggests a kind of housing hilly with a gradual slope toward the south and a garage for parking below the “hill.”

And for identity—the only genuine solution to the problem of identity is to let each family gradually build and rebuild its own home on a terraced superstructure. If the floors of this structure are capable of supporting a house and some earth, each unit is free to take its own character and develop its own tiny garden.

Although these requirements bring to mind a form similar to Safdie’s Habitat, it is important to realize that Habitat fails to solve two of the three problem discussed here. It has private gardens; but it fails to solve the problem of connection to the ground—the units are strongly separated from the casual life of the street;—and the mass-produced dwellings are anonymous, far from unique.

The following sketch for an apartment building—originally made for the Swedish community of Marsta, near Stockholm— includes all the essential features of a housing hill.

|

| Afartment building for Marsta , near Stockholm. Therefore: |

To build more than 30 dwellings per net acre, or to

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A pattern language»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A pattern language» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A pattern language» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.